Over the past 10 years I’ve been on the first cap tables of three startups for which I’ve been responsible for closing their capital-raising efforts. I’ve been in over 200 investor meetings as part of the operating team, and have raised money from the smallest angel investor to the biggest European VC funds and some of the world’s largest corporate investors.

My present role as head of corporate development at Founders Factory has me on the other side of the table, assessing the materials and pitches of many early-stage startups, as well as running the internal Founders Factory program designed to assist our cohort close out their next round of financing.

I remember our managing director, Jim Meyerle, coming back from one of the many pitch days he attends, in full wild-eye mimic of a particular startup’s presentation as they asked with syncopated emphasis whether or not we could “imagine a world without pizza.” It’s true, I can’t. And if ever there was a reason to invest, it’s that. But that wasn’t the point Jim was making.

At Founders Factory we don’t hire actors to help the cohort present, we don’t prescribe a rigid formula for how they should pitch. That’s as much a function of the type of accelerator we are; we take in fewer cohort members and provide a much more bespoke program to each, as it is a point of principle.

But if there has been a complaint of pitch and demo days it has been the sometimes cookie-cutter approach to the pitch; and sometimes that approach has led to the presenting teams delivering an inauthentic, sometimes damaging, caricature of themselves and their product.

New founders are ravenous seekers of knowledge — and demand guidance. Generally, anything too equivocal is not well-received. But the truth is, equivalence is the rule when it comes to early-stage tech investing, particularly at the pre-Series A stage. The reason for that is easy to intuit: The success for any early-stage tech business is too sufficiently complex to predict. Even the super-forecasters require systems at a certain level of maturity before they can confidently predict the next 12-18 months.

Very early-stage technology businesses are not at this stage. Success is almost certainly a matter of irreducible uncertainty; winners sit in Taleb’s fat tail — which means even the best investors aren’t able to deploy too much in the way of data to guide their decision. Instead, they say they make their decisions on intangibles: a feeling for the team, the sub-text in the story that speaks to urgency, innovation, size of opportunity and a sense of the Big Mo.

The challenge — and the opportunity — is that these intangibles are entirely subjective. Like a Barthesian death, the salience of the sales message is often in the ear of the beholder.

The secret to selling is to tell a simple, coherent and vivid story designed to emotionally engage — and intrigue — the investor.

And, whether they know it or not, the decision is likely made at the level of their unconscious, fast-processing, associative, system — Kahnemann’s System 1 — and later justified by their slower, apparently rational but often simply self-certifying System 2… which will throw up ironies like a “too good” pitch alienating the investor because the presenter has focused too much on honing their pitching skills to the point of precision, while forgetting that pitching is not really pitching — it is sales — and sales is subtle. They have failed to do the job of selling.

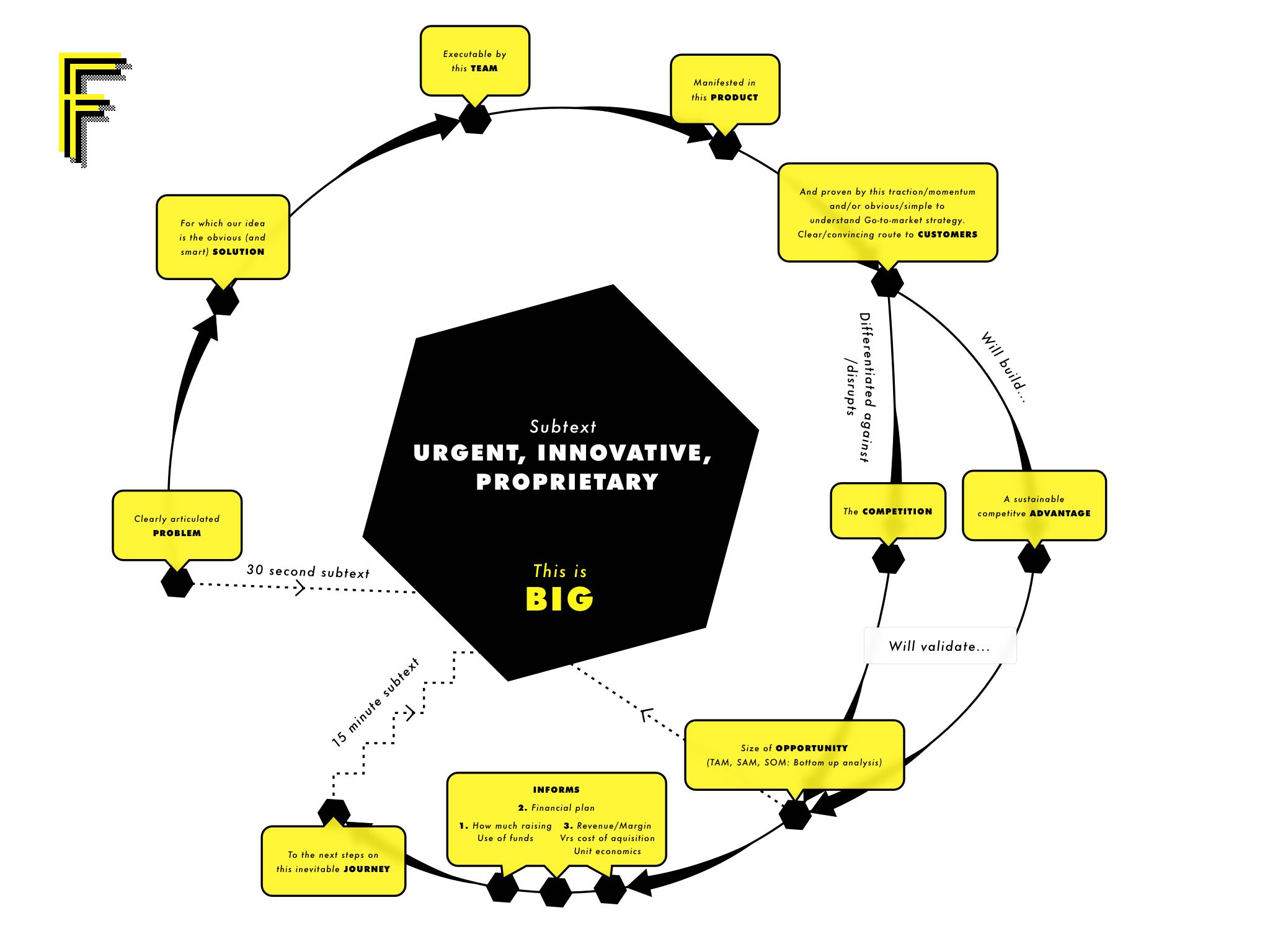

So before we collapse completely into nihilism, what guidance is there for the early-stage pitch? We help our cohort understand that, when speaking to a listener’s System 1, one must deliver a narrative, a coherent story that follows a dramatic arc. One must ping their emotional senses, spark their interest, have them fall in love.

They need to believe that you know what you are talking about today and will be able to credibly navigate an uncertain, but potentially industry-altering, future. They need to believe you can inspire employees, partners and investors. They need to trust you, which is where storytelling plays another significant part, because it makes your product more available, and therefore more believable. When that is done, your product and investor materials need to be sufficiently robust to allow their apparently logical System 2 to confirm their bias toward you.

We encourage you to think of your investor deck in terms of a story:

You need to know that what works for one investor will not work for another. That is what subjectivity is all about. It’s entirely natural, and utterly unavoidable, to be rejected by some.

Therefore, allow me to offer two canonical pieces of advice when it comes to pitching:

Be the custodians of the magic

Very early-stage tech investors are, by their very nature, embracers of the future. If they weren’t, they’d be more like Charlie Munger, waiting and watching for months, even years, before investing — and then only after they’d wrung the decision through many mental models to make sure it isn’t one corrupted by bias.

Very early-stage tech investors want to be shocked and impressed in equal measure. They want you to tell them something they don’t already know. They want you to demonstrate that there is some insight in your study and/or your experience and/or your flat-out genius that is just bloody-well bone-crushingly smart. And they want to believe that it is you — and precisely just you — who will deliver on its promise. They want magic. And they want you to be the custodian of it.

Your job is to convince them of this.

I recall how Gerard and Archie, founders of Vidsy, managed to change my mind about them in just this way. At first blush, I put Vidsy down as a less-interesting Upwork… yet another creator marketplace. But they said two things that I neither knew (although, with hindsight, it was obvious — the best kind of insight) nor was likely to know.

Demo and pitch days foster a formulaic approach that often works against the presenter.

Firstly, branded video advertising on the newest social platforms were jarringly anachronistic. Totally tone-deaf. The incumbent creators weren’t creating content that was sufficiently lithe to speak to the constantly shifting consumer zeitgeist: face-swap filters, time-lapses and Chewbacca masks. And second, Archie was a digital film graduate, so he knew there was a swarm of young creatives with the time, energy and desire to spin up volumes of high-quality, platform-consistent content.

The team uniquely lived on both sides of their marketplace and helped me understand that the spin they put on their product was the most natural thing in the world to provide the solution.

The guys building the Flourish product had spent years as a data visualization agency creating jaw-dropping interactives that, for example, animate all the world’s planes or ships or squish countries to show how they compare on any given metric. But here’s the rub: Duncan is a published author with best-selling books about climate change under his belt; Robin is an Oxford-educated Computer Science PhD who, when the flu has him laid up on the couch, finds proofs for N-P quite-hard math problems.

They had the hard-won insight, born of real-world experience, that there’s a particular way to structure responsive interactive visuals designed to tell stories with data. Over the years they honed that approach until they felt ready to make a tool kit that would let others do the same — because that product, specifically the telling stories bit, does not exist today. I didn’t know that. They understood that democratizing their skills is a much bigger and more powerful idea than hoarding them.

Practice in the wild

This is the single best piece of advice I can give. You can read tons of articles like this and others on the internet. You can ask mentors a thousand questions (and probably receive a thousand different answers) about how to pitch.

But I’ll repeat: Pitching is not pitching — it is sales. And sales is subtle; it is about convincing other human beings to buy something.

Actual pitching is subtle; although there are guidelines, they shouldn’t be over-thought or over-determined.

You may have been raising for weeks or even many months, but you have been convincing people all your life. Pitching, like all skills, is better delivered coming from your System 1 approach — not your System 2. Just as is driving, riding your bike and playing your virtuoso violin. Get your pre-frontal cortex out of the way, because it can cause the yips, and instead rely on those primitive brain systems that find optimal processes via trial, error, feedback and tweaking: The original lean methodology.

Through repeated practice, your sophisticated subconscious will work out an effective rhythm and pace to your presentation, it will adapt to questions and react to investor un-said cues. Like a good comedian, you can guess what the audience will be receptive to, but you won’t know until it has been tried. Then you tweak and tweak until it is the best it can be, and naturally flows.

“System 1 is the superpower behind all the most amazing human feats that we can achieve. With enough practice, you can direct it to take you anywhere you want — whether it’s the Olympic Games, or the most vaunted chambers of Silicon Valley. System 1, when trained and then left to run on its own accord, will put you in flow — a state of sync with yourself and your audience.” — Lauri Järvilehto, CEO of Lightneer and author of The Nature and Function of Intuitive Thought and Decision Making (Springer 2015)

The homunculus that believes itself to be in control of yourself is actually an under-performing, over-confident, energy-guzzling, often sabotaging imp that is best deployed only when really needed.

So practice, practice, practice — and watch it fall into place.

Like magic.