Mimicking nature’s most elegant designs has become a popular method for creating equally elegant robots (close, anyway) — but using nature’s raw materials, too? That’s what researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute have done, creating a tiny light-controlled stingray with a solid gold skeleton that moves using reconstituted rat muscles. O brave new world!

The researchers, led by Harvard’s Sung-Jin Park and Kevin Kit Parker, started with the skeleton, working at ~1/10th scale of the batoid fishes (comprising skates and rays) on which it is based, and recreating a simplified version of the creatures’ actual anatomy.

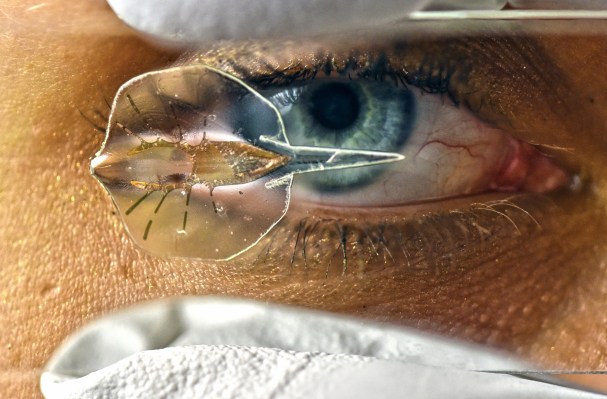

They started with the skeleton: Gold is flexible and nonreactive, and they designed the spine and ribs to have a natural convexity. Around the ribs they cultured rat-derived cardiac muscle, genetically modified to respond to light instead of the usual electrical signals from the nervous system. The whole thing is encased in an elastomeric sheath very much in the shape of a small ray.

Here’s a more detailed diagram of the layers and motive forces.

NB: In a situation like this, “robot” doesn’t adequately capture the essence of the thing. Yet, despite containing living cells that must grow and feed, it’s not quite an animal, either. Its creators went wild with the nomenclature: “tissue-engineered soft robotic ray,” “biohybrid system,” “artificial animal,” and “bio-inspired swimming robot,” none of which completely satisfies. “Biobot” — or maybe “growbot,” since they’re cultured, not assembled — seems a catchier option.

The motion batoid fishes use to get around is simple and elegant: Their bodies are essentially one big fin, which they undulate in controlled waves, sending themselves backwards, forwards or turning to one side.

In the artificial ray, the muscles only have to exert themselves downwards when stimulated; the curvature of the gold ribs in the opposite direction provides the counterforce and when the muscles relax, that part of the fin flexes back upwards. Nutrients are provided by the solution in which the whole thing is immersed.

Turning is accomplished by stimulating one side of the body more strongly than the other, and the muscles’ photoreactive nature makes them move naturally toward the source of the light. You can see the cyber-critter in action below:

Taken individually, each aspect of this little biobot is remarkable, but the synergy created by adding them together makes the whole thing astonishing. Every aspect of the thing is either robotics-built to resemble biology, or biology-modified to resemble robotics. The scope and precision of the researchers’ control over every process is plain to see, and this biobot represents a new bar in a field where the accomplishments are already almost beyond belief.

It was enough to get the team a cover story in Science — and it’s so visually striking that the journal ran a whole story on how it photographed the ray.

But let’s not get carried away in hyperbole such as that the researchers have created artificial life or some kind of horrifying “Island of Dr. Moreau”-esque monstrosity — it’s definitely too cute for the latter, and the former overstates the case.

For all the expertise and advances contained within this research, the resulting product is, essentially, purely mechanical. There is no nervous, digestive, circulatory, perceptive or reproductive system in place; it truly is a biologically enhanced machine rather than a mechanically enhanced organism.

And make no mistake: As difficult and impressive as the creation of this artificial ray was, it represents a collection of solutions to the easy problems in replicating life’s subtle and powerful tools. Even the simplest nervous systems are beyond our power to accurately simulate, let alone recreate — and the human brain is many orders of magnitude larger and more complex — in fact, it is almost certainly the most complex system we know of.

That said, this level of fusion between biological and mechanical engineering is a truly amazing accomplishment. Biomimesis is found at the bleeding edge of robotics and other sciences for good reason: Only very recently have we begun to approach even the most elementary levels of expertise with which nature has crafted her creatures for billions of years.