NASA scientists are bringing one of the most powerful computers in the world — just recently given a tune-up — to bear on the question “Where do stars come from?” So next time your toddler asks you that, you’ll be able to say something smart, like “hyper-dense elongated stellar filaments, child.”

Pleiades is NASA’s flagship supercomputer, and over the last few months its keepers have upgraded it with some hot new hardware. Sixteen racks of old and busted Westmere Xeon X5670s made room for 1,008 Broadwell nodes, bumping peak theoretical performance to 6.28 petaflops. That would put it just above Höchstleistungsrechenzentrum Stuttgart’s Hazel Hen and about even with the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre’s Piz Daint.

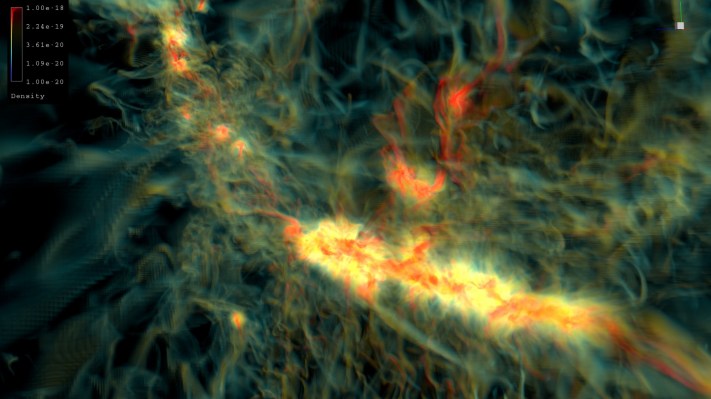

That’s good, because the researchers need every flop. Using data gathered from a number of telescopes and instruments, as well as theoretical models, the ORION2 star formation simulation incorporates a wide array of forces: “gravity, supersonic turbulence, hydrodynamics (motion of molecular gas), radiation, magnetic fields, and highly energetic gas outflows,” according to a NASA news release.

The results, helped along by the visualization team at NASA’s Ames Research Center, are hypnotizing. This video shows a “giant molecular cloud” over a period of 900,000 years as simulated by ORION2:

A zoomed-in version can be seen at the NASA blog post.

Astrophysicist Richard Klein, from UC Berkeley and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, leads the star formation study.

“Without NASA’s vast computational resources, it would not have been possible for us to produce these immense and complex simulations,” he explained in the release.

So what did they actually learn? Well, when two regions of interstellar gas love each other very much, they succumb to gravitational forces and become turbulent, eventually collapsing into stellar clusters in chains and forming stellar nurseries.

That more or less tallies with direct observations, but our window on the cosmos is necessarily somewhat limited, so we can’t just watch a protostar form over a million years or two. Models and simulations help with that.

Better resolution is the next step: Simulating at a more precise level would let the researchers study the formation of stellar disks, thought to be the structures that eventually coalesce into planets.

“Understanding star formation is a grand challenge problem,” Klein said. “Ultimately, our results support NASA’s science goal of determining the origin of stars and planets, as part of its larger challenge of figuring out the origin of the entire universe.”