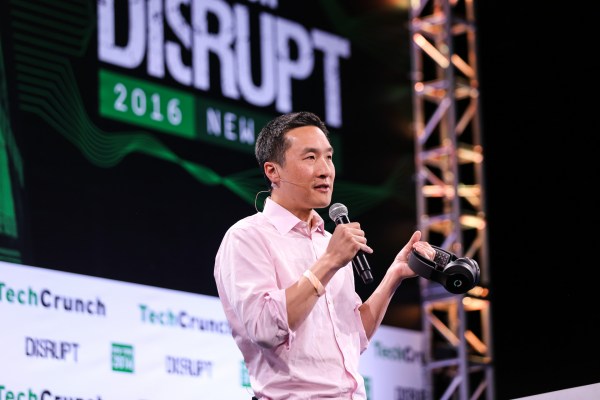

Halo Neuroscience wants to build a new category of wearable. Not for passively tracking human activity, as so many existing wearables do, but for actively and positively influencing physical abilities — or that’s the claim — using an existing neurostimulation technique called transcranial direct current stimulation. The team demoed their wearable onstage today at TechCrunch Disrupt NY.

So what exactly is transcranial direct current stimulation? It refers to a long-standing brain stimulation technique that involves applying a very small level of electric current to the wearer’s brain via electrodes placed in contact with their scalp — with a wide range of experimented applications over the years, such as treating depression, chronic pain or brain injury.

Typically, it’s fair to say that the technique has mostly been focused on specific medical use-cases up to now, rather than being applied as a wider consumer proposition. But it’s that broader potential market Halo Neuroscience is hoping to open up — if their tech can live up to their claims.

Their first wearable, the Halo Sport, is designed to influence a region of the brain they say is involved in sports and fitness learning — thanks to the specific positioning of the electrodes over the motor cortex. The device is being targeted at elite athletes to use as a training aid to improve their performance.

At first glance it looks rather like a pair of Beats headphones, but you also must attach two neuroprimers (as they’re calling their electrodes) to the inside of the headband, then spray your head with water to allow for good conductivity before the battery-operated device is good to go. A companion app allows for control and tracking of usage.

The headset does not need to be worn during every training session, but rather should be used when athletes are doing a training session involving “a high volume of quality repetitions,” according to the co-founders — albeit predicting your training performance ahead of time isn’t exactly an exact science.

[gallery ids="1319482,1319462,1319481,1319483,1319109"]

Their core claim is that neurostimulation of the brain via their device will accelerate an athlete’s learning process when applied during an intense training session — including, they say, positively influencing the rate at which particular sports skills are honed, as well as helping athletes make general strength gains and improve performance explosiveness.

They claim they can “reproduceably” show they can generate gains above a control group, noting specifically when it comes to skill acquisition that the learning rate is “about 2x” better with their device (they say they have tested it in controlled lab conditions with around 1,000 subjects).

“When athletes train, much of the benefit in strength as well as skill comes from the brain learning to use the body better… That’s neuroplasticity. And what Halo Sport is doing is it’s increasing neuroplasticity during that training period so that the brain, which is already getting better during that, gets better a little bit faster during that period of training,” explains co-founder Dan Chao.

“There’s a very extensive body of research worldwide… showing that this technology, transcranial direct current stimulation, can increase the rate of motor learning when it’s applied to these points over motor cortex. It’s been shown by multiple groups in peer-reviewed studies in healthy people, in stroke patients, and we’ve confirmed that with our own [sham-controlled, randomized controlled trials] data. Now what we’re doing is we’re applying this specifically to athletic training.”

“When paired with athletic training our claim is that you can stand to benefit from accelerated neurologic gains in your athletic training,” he adds. “Almost 100 percent of athletic training is just based on repetition. It’s repeating a skill over and over and over again, or even in the gym for strength — strength training is based almost entirely on repetition, just do it over and over and over again.

“Certainly part of that is for the sake of our muscles, to make them stronger. But a big part of that — and I think this is under-appreciated in the field — is to literally make your brain stronger and more skilled. That’s where we want to come in.”

The co-founders reckon a wide range of athletic disciplines potentially stand to benefit from their wearable, but say they are seeing early interest from baseball, having ceded some beta units to athletes to test the tech ahead of a commercial launch later this year.

“Baseball has been an interesting place for us,” says Chao. “A very systematic and science-based approach has crept its way into player development. Especially smaller market teams — they don’t have the luxury of just buying players, they need to build players. It’s cheaper for them to do this.

“We’re seeing in the sport a lot of these smaller market teams have developed a competitive advantage in player development — to use sports science to accelerate the development of young players so that they can have them on their team before they hit free agency. So that’s been a great place for us so far. There’s been a lot of interest from Major League Baseball.”

Prior to founding Halo Neuroscience, back in 2013, the two co-founders had worked for most of their careers at another neurostimulation company, NeuroPace, which makes an implanted medical device for epilepsy sufferers that uses neurostimulation to try to stop seizures at the point they are about to start.

“As we worked on this [NeuroPace device] for more than a decade, one thing that really became apparent was that there’s this enormous potential in technologies that interact with the brain. It’s this really powerful way to help people reach their potential, to improve the lot of humans, basically,” says Chao.

“The problem is so many of the technologies that are so powerful on the medical side of things — it’s very invasive. It’s expensive, it’s invasive… That’s appropriate for some patients, but in and of itself it’s not a technology that’s really changing the world.”

At the same time he says the pair had been tracking research developments in non-invasive neurostimulation — and became convinced there was enough of a body of evidence that the technique could be used to influence the rate of learning “non-invasively, safely and effectively with an external device” to launch their own startup.

“Now we’re at the point where there’s hundreds of articles every year about this in peer-reviewed journals. And this whole world of science working on this technology,” he adds.

They’ve been working on the startup for almost three years at this point, and have raised some $9 million in funding, coming out of stealth to launch pre-orders for the Halo Sport this February.

Investors in the business include some very well known names — Andreessen Horowitz, Lux Capital, SoftTech, Xfund — along with a newer, neuroscience-specific firm, Jazz.

The lengthy (and stealthy) development process was down to the team needing to build up their own body of data. The entire first year was spent looking purely at data generated by their core tech, with no thought of finished products or target markets, says Chao.

“Our goal for the first year was to build our own device and to test the heck out of it,” he says. “We tested a thousand people before we made any decisions on product. It was really the data, specifically the data that came out of our motor cortex stimulation program that led us to sports.

“Brett and I didn’t found a sports science company. We founded a neurostimulation company.”

They’re aiming to ship the Halo Sport in the fall of this year, with the discounted pre-order pricing set at $550 and RRP of $750. (It’s worth noting the primers are also “semi-disposable” so will need to be replaced around every three months (based on “average use,” they say).

How much demand is there for this sport-focused wearable? They won’t specify how many units have been pre-ordered at this point, but couch the early demand as “good.” They’re not currently taking any more pre-orders, but say they plan to open up a second wave in “about two months.”

In terms of additional revenue streams, beyond the cost of the hardware, the basic companion app will be freemium, should individuals want to buy the product, but certain more pro features will be unlockable via in-app purchases.

There’s also a SaaS component to their business model at the elite athlete level — with different levels of service bringing in different rates of subscription revenue.

Are there any downsides to using the device? Does it perhaps cause headaches with prolonged use? The founders concede it’s unlikely to feel exactly pleasant to use. They describe the sensation as “very tolerable,” rather than pleasing, with Chao adding that: “Most people don’t like it but almost everybody — they don’t mind it.”

He says they have also monitored usage for specific “obvious problems” — such as headaches and scalp pains, as well as testing for impairments to cognitive and motor skills — and say they haven’t found “any real changes.” So the claim is no major negatives, beyond perhaps feeling a little buzzy.

The ultimate goal of Halo Neuroscience is to end up with “a fleet of these products,” says Chao, addressing all sorts of consumer market use-cases — if they can convince people to don a headset to speed up their learning.

“We’re starting with the motor cortex but why couldn’t we develop a neurostimulator to hit that part of the brain that’s responsible for memory? And instead of doing memory games on its own if you paired it with neurostimulation that could be a much more powerful combination,” he says.

Another interesting potential use-case is back in the medical space, with Chao flagging up what he says is promising data on rehabilitation of motor skills for stroke victims using the neurostimulation technique. The startup is sponsoring a clinical trial to investigate this use-case.

“The scientific data looking at neuro-rehabilitation for motor stroke victims is really good with this technology. You can really raise the ceiling of recovery of what is possible. And also accelerate the rate at which you obtain this new ceiling,” he says.

“About a million people in the U.S. suffer from a stroke every year, and about half of them suffer from some sort of motor symptoms — they can’t move a leg or an arm or something like that. And their opportunity for improvement is very poor. Physical therapy doesn’t work very well, especially in the chronic phase.”

Judges Q&A

Q: What was he demonstrating there?

A: That was just an example of pairing neurostimulation with athletics training — and in this case a strength-based training session. But you can imagine doing more skill-based work or endurance work.

Q: Do you wear it before you exercise, during, after?

A: Ideally during and after. If it’s not conducive to during then if you do it just before that’s fine – for example working with Olympics swimmers and you obviously can’t wear this in the pool. So in that case you would wear it before, when you’re warming up. Take it off.

There’s an afterglow of an hour. So you would still have that hour of benefit from the neuropriming.

Q: The results that you showed, were people actually wearing it? And will those last over time if they stop using the device?

A: Yes the results are durable. They are maintained at the same extent. The difference between the control group is maintained over time.

Q: It’s a beautiful piece of hardware, a very consumer-facing name. Is that a part of the strategy here. Because you not only have to get these distributed, you have to educate the market as to what this is, what shocking… the brain will do to you, things like that. So you’re an education company as well as a hardware sales company?

A: That’s exactly right. Our goal for this year is really to educate and inspire the market.

Q: How do you do that?… Having Olympic teams is a big marketing push, but what’s going to be able to educate the mass market that this is a viable thing to do?

A: Our strategy is top down. We want to use our elite customers as our mouthpiece, generate PR with these individual athletes and teams… Top down is a very viable way to do it.

Q: This is something that you think over time as a performance enhancer gets regulated, or this is what every single athlete in the world has to do to keep up?

A: Regulation really starts around safety and we’ve gone to great lengths to demonstrate safety, and so has the scientific community.

There’s scientific published literature published on over 60,000 sessions.

Everything that we’ve seen so far suggests that it’s safe, so…

There’s plenty of techniques and products that are performance enhancing that are legal — in fact most are. Where the clear line is is around safety.

Q: What could go wrong? I’m putting electric spikes on my head. What could go wrong?

A: Very little could go wrong. We stack those odds in our favor. There’s hardware and software safety features that we don’t really talk about we just want our users to take for granted. So, for example, overuse could be a concern. We would lock people out after 30 mins per day. There are current limiters so that the device checks itself 1,000 times per second so that if it were over-delivering stimulation it would gracefully shut itself off. So there’s features and functions built in.

Q: How does it work with wet hair?

A: It works great with wet hair. In fact it works better.

Q: Aren’t there lots of physical activities that take longer than 30 mins?

A: You still benefit from the afterglow of an hour, so that would buy you about 90 minutes of neuropriming.

Q: What is the consumer price point? And what margins do you expect?

A: $750 is the price point. And I shouldn’t disclose the margins but they will be good.

Q: Are you ready to produce at scale? Does your team have experience doing that?

A: Yeah we do. We built the implantable neurostimulator which was a very complicated piece of hardware to build.

This device we’ve already cut steel in China. We’ve already picked our vendors, our final assembler, our injection molder, so we’re well on our way. We should be able to deliver it in the fall.

Q: Do you have data for the rehabilitation portion of the application?

A: Yes, that takes time. We should have data at the end of the year. We’ll expect 24 subjects completed by the end of the year. But there’s been multiple trials looking at a stroke model. And perhaps the best data in all the scientific literature comes from the stroke model.

Q: Do you reshape the electrodes or the electrical patterns for different use cases?

A: You do slightly, and you’re able to do that through the app. So you could target the hands and arms. You could target legs… We would allow you to do that through the app.