No one else ever sees most of your camera roll. But if you’re brave enough, your close friends might enjoy peeking at every photo, video, and screenshot, not just the best ones. So call it creepy or the next frontier in social media, but that’s what Shorts does. It’s the new iOS app from the makers of Highlight, the hyped location app startup of 2012 that fizzled out and is now pivoting.

The idea of Shorts is to give people the most raw and intimate look at your life possible while still maintaining a shred of privacy — like seeing someone wearing short pants.

Check out our demo and interview with Shorts’ developer

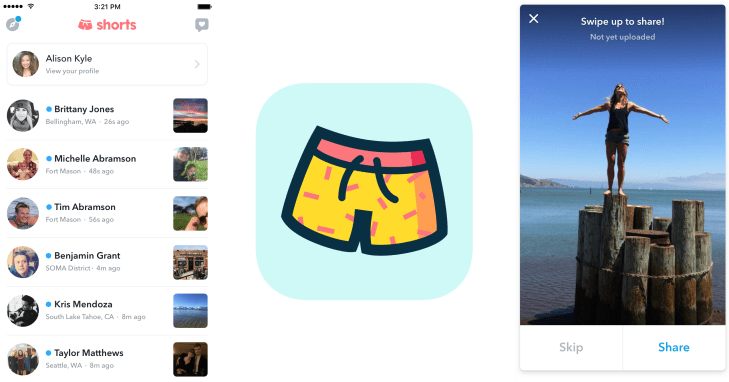

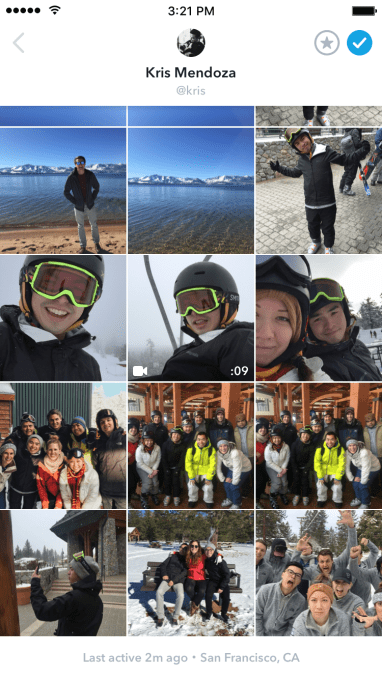

Each time you use Shorts, it asks you to share everything on your camera roll since you last opened the app. You swipe through one at a time, sharing or redacting each photo and video. You can set those you share to be publicly visible, or only shown to approved friends.

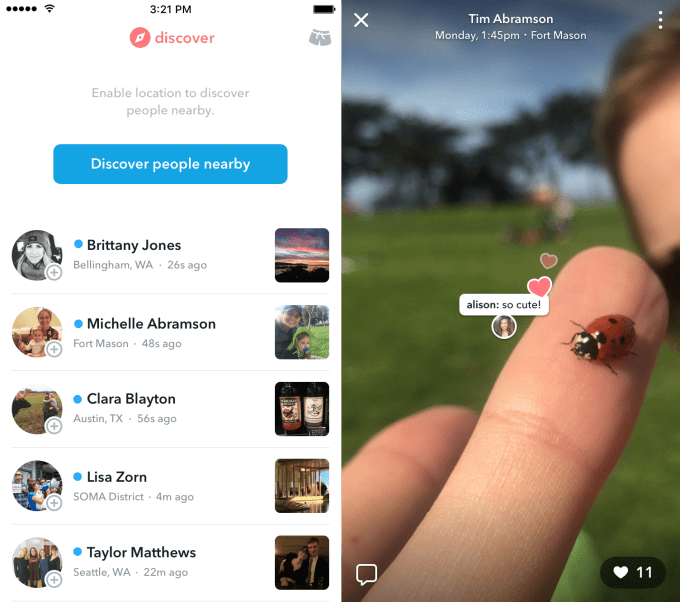

Your followers can choose you from a Snapchat Stories-esque list and swipe through your shares, Liking or leaving comments. Since there’s no central feed, you don’t have to worry about annoying friends by posting too much. And the Discover feed features people nearby and others you might want to follow.

It’s aggressive, no doubt. But while some are sure to bristle at the exposure, beta testers ended up sharing half of everything on their camera rolls. And because there was suddenly an audience for everything they captured rather than just the highlights, testers ended up shooting two to three times more photos and videos.

“Most of the interesting social services that have emerged that people feel very comfortable with today pushed people a little bit outside of their comfort zones when they started” says Highlight founder and CEO Paul Davison. Putting your face on the Internet with Facebook, tweeting your lunch, or snapping your private life all seemed a bit aggressive at first too.

Shorts might be the natural progression of oversharing, or another crackpot social app few want. Lightning in a bottle is hard to predict.

Shorts is Davison’s second attempt to get us to meet the people around us. In the Discover section you’ll see people who share publicly who are friends of friends and your Twitter contacts, but also people nearby. If you thought it was weird when someone’s reputation precedes them, now their most intimate moments will precede them.

Davison says Highlight will remain available but his team is now focused on Shorts. During development, the team actually built a much pushier app called Roll that automatically shared every photo you took in real-time without asking. That proved to be too scary. Not every horrible selfie, inane screenshot, or racy video needs to be broadcast.

Despite seeming intense, Shorts does give you full control over what you share, and seems more natural if you lock your account down and just add your significant other, closest friends, and/or family. These people could get a kick out of your day-to-day camera trail while your distant acquaintances on Facebook might be bored to death.

Despite seeming intense, Shorts does give you full control over what you share, and seems more natural if you lock your account down and just add your significant other, closest friends, and/or family. These people could get a kick out of your day-to-day camera trail while your distant acquaintances on Facebook might be bored to death.

“We’ve designed it so you can be as public or as private as you want” Davison tells me. “The existing services weren’t designed with this high frequency sharing in mind.”

Highlight has stayed lean and is still surviving on the $5.5 million it raised back in 2012 and 2013. It won’t have to monetize just yet. But if the app proves popular, you can imagine brands having their own entries in the stories list that you could paw through.

For now, Shorts will have to convince us that the remnant inventory of our camera rolls, the things we don’t deem cool enough to share elsewhere, deserve to be shared.. While Shorts is built to be efficient, the cognitive overhead of deciding if each shot is worthy of posting could prove tedious.

And if Davison wants this to be a hit social app, it’s curious that he’s launching it with a big global press push. Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat — they all started with geographically clustered groups of users and grew naturally. Not like this. Social apps die when you’re the only person you know using them.