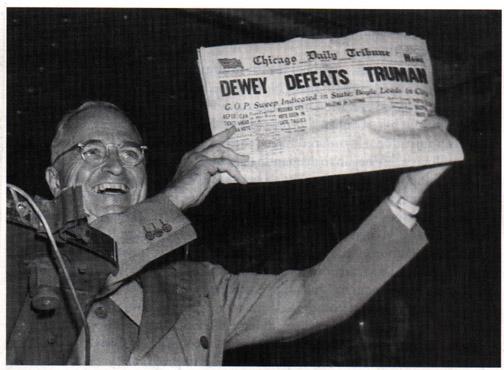

As the polls were closing for the 1948 presidential election between Thomas Dewey and Harry Truman, the Chicago Tribune went to print with the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” based on early voting predictions… It led to the forever-immortalized photo of an eventually elected President Truman triumphantly holding that same edition of the paper and boasting, “That ain’t the way I heard it!”

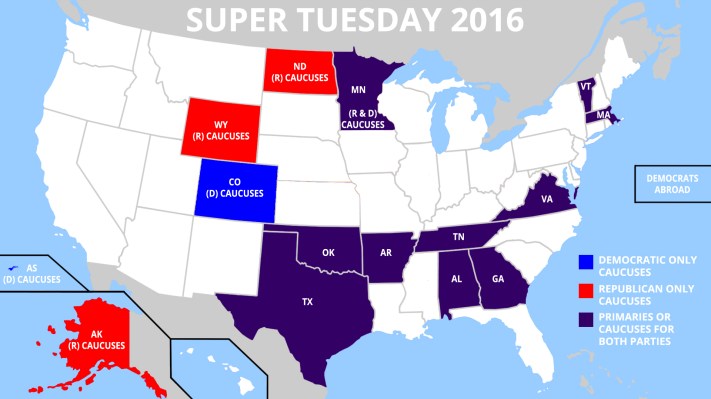

Nearly seven decades later we’re still seeing incorrect predictions in political races. Take the 2016 Iowa caucus for example, where Ted Cruz triumphed despite expert predictions to the contrary. It’s enough to make you wonder: What data is used to create these predictions? And with today’s technology, why isn’t it more accurate?

Big data has gotten, well, big over the past few years, with the advent of storage systems like Hadoop, Hortonworks and Cloudera to manage the 2.5 quintillion bytes of data being created every day, a global Internet population that has reached 3.2 billion people, and a dramatic increase in both computing power and storage capacity. In fact, the real magic of predictive analytics is big data, as noted in this insightful article on the VersionOne blog.

So why aren’t we living in a world where computers solve crimes, drive cars, cure sicknesses, and accurately predict political races?

The reason is because it’s not enough to just store, access and process data. Even sophisticated algorithms will only get you so far.

The key to successful machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms comes down to two factors: huge quantities of timely and accurate data.Without these, the whole premise of predictive analytics falls apart.

As the frequent inaccuracies behind political polling and other predictions suggest, finding both timely and accurate data is easier said than done. There are four typical methods you can use to acquire data, and the each of them ties directly to the value of your data.

Photo courtesy of Flickr/David Erickson.

1. Required self-declared data

The first and most basic way companies acquire data is through government organizations that require individuals and businesses to provide those entities with their information.

Examples include registering a business with a state, companies or individuals paying taxes, census registration, individuals registering for a driver license, Social Security and even individuals declaring political party preference.

Because of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), some of this data is publicly available. But collecting this type of data has both advantages and disadvantages.

The quantity and breadth of data through these sources is robust, but the information is not particularly timely or accurate because it is collected too infrequently and human nature is constantly changing. The full census happens only every 10 years, driver licenses last four to six years, and people move every six years and change jobs every four years.

Typically, data becomes invalid at roughly the rate of 30 percent to 40 percent annually. After two and a half to three years, any list you have is completely out of date.

Additionally, the accuracy rate of required self-declared data is typically low because people are not incentivized to provide accurate data. People are often suspicious of governments and therefore only supply just enough information to avoid violating the law.

2. “Brute force” self-declared or observed data

Photo courtesy of Flickr/WyoFile WyoFile.

When organizations like Dun & Bradstreet and Hoovers call people and interview them, they are capturing self-declared data almost by brute force. It’s not volunteered data because individuals aren’t sharing it publicly, but it’s not required data because people can decline to participate without violating the law.

When other organizations use web crawlers to collect people’s information, they are acquiring observed data by brute force. This data can be either self-declared or observed and therefore has a higher accuracy rate than government data. It’s not subject to as many faulty interpretations, biases and dishonest responses.

Political polls frequently rely on this kind of data collection. Organizations like Pew Research Center survey likely voters to interview them on their level of engagement in the election, perceptions on candidates in play and voter preferences. Because this data is self-declared and not required, interviewees are more likely to provide honest answers.

While this data collection method does improve the accuracy, it is not updated often enough because it involves a labor-intensive process: Individually surveying hundreds of U.S. citizens on their voting preferences to predict the polls takes considerable time and may overlook the chance of shifting perspectives following a recent debate, public statement, etc. Therefore, with brute force data, timeliness suffers.

3. Volunteered self-declared data

Organizations can collect huge volumes of self-declared data on social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

The Pew Research Center found that 74% of online adults use social networking sites. Statista reported that more than 1.5 billion people are actively using Facebook while 400 million are active on Instagram and 316 million are tweeting up a storm.

Social media data can be especially useful when taking a pulse of consumer perception around current events, such as the ongoing presidential elections. With people updating their online profiles and posting status updates 24/7, this is some of the timeliest data the world has ever seen.

It’s still not highly accurate, though, because it’s self-declared. We show our Facebook friends only the life we want them to believe we have. We’re curating our personal brand. Have you ever seen anybody admit they were fired on their LinkedIn profile?

4. Crowdsourced observed data

Technology that provides value in our personal or business life can observe our behavior in the process.

As we make purchases, travel and make phone calls, technological systems observe our behavior. These systems can amass massive amounts of data without asking us, purely through the power of observation.

Amazon is just one example of a company that is crowdsourcing data across multiple vendors, individuals, geographies, industries, etc., with 294 million active customer accounts worldwide. The company is processing so many transactions that it saw net sales increase 23% to $25.4 billion in the third quarter of 2015.

With timeliness and accuracy both amazingly high, crowdsourced observed data is the most sophisticated and accurate source of data available.

The optimal blend

Photo courtesy of Flickr/DonkeyHotey.

Generally, the harder it is to acquire data, the more valuable it is. The best way to ensure you, or political pollsters, have timely and accurate data is to use a combination of all four sources. This optimal blend creates “high-definition” data: a collection of crowdsourced observed data blended with the other three sources to provide true predictive value and accurate results.

It’s the only way to produce maximum resolution and maximum clarity — and predict more accurate political polls.

But political polls are just one example of how predictive intelligence is playing out in our daily lives. It’s important to note that any intelligence is only as good as its source, and with new ways of gathering data popping up every day, the ugly truth is that there’s not one crystal ball that gets it right 100 percent of the time. Take social media for example: As we saw in President Obama’s successful social networking campaign in 2008, social media’s role in politics is continuing to grow. The abundance of data hosted through social channels opens a significant opportunity for real-time readings of nationwide sentiment on candidates and campaigns.

As new forms of data and analysis continue to emerge, data-based predictions will only get more and more accurate, but take them with the grain of salt they deserve. What is guaranteed is that this election season will be fascinating to watch play out–and we’ll only know what will happen for certain in November.