Food tech is big these days — Grubhub, Blue Apron, Instacart — but pretty web design and polished communication strategies aren’t enough to build a sustainable food business. No company will provide attractive gross margins without creating and executing a sustainable new paradigm for food delivery.

It comes down to perishability: Fresh food breaks tried and true delivery models, and drives costs through the roof.

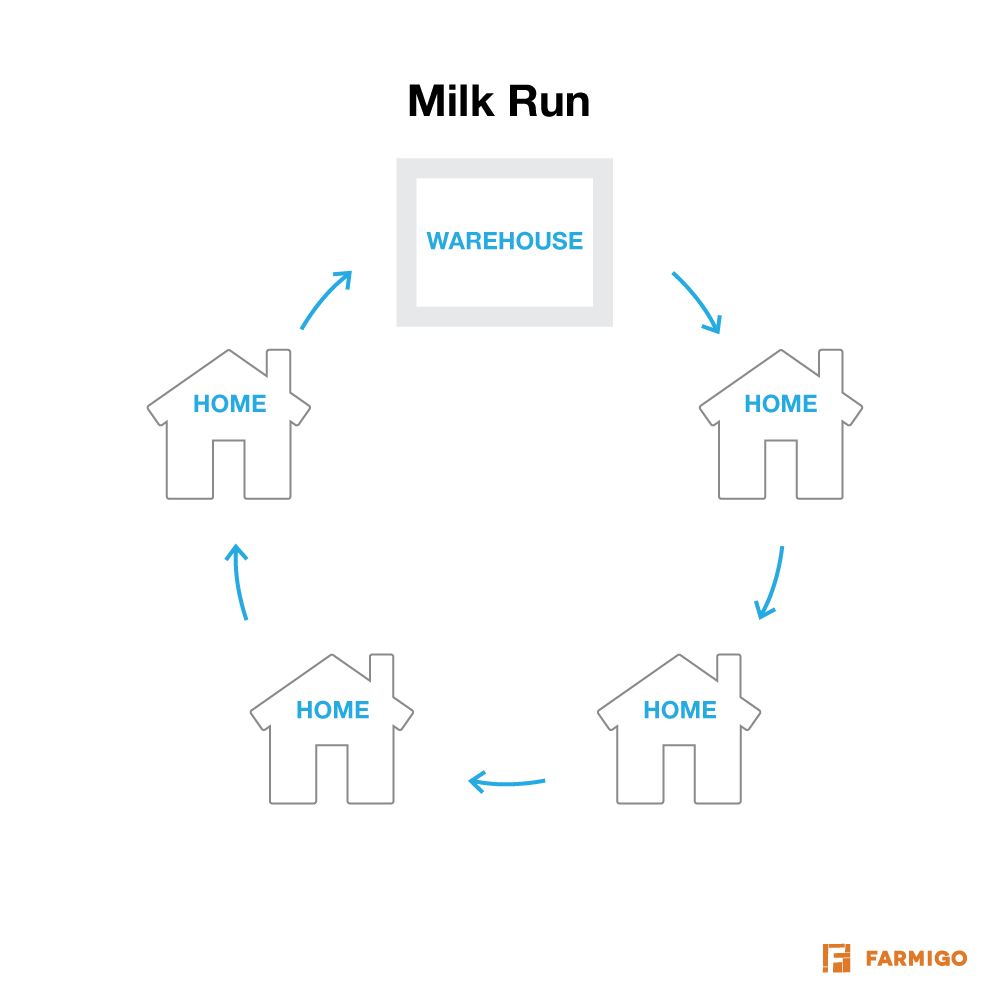

In the mid-20th century, a visit from the milkman was part of the weekly routine. He’d start his morning at a dairy, then head door to door with his refrigerated truck full of freshly filled bottles, changing out old empties for new.

The Milk Run delivery model thrives when there’s a stable route that can be continuously optimized as new deliveries are added; it’s direct, efficient and provides reliable sales to the dairy — everyone wins. However, the Milk Run model has a critical weakness: It doesn’t work whenever any variability is introduced; for example, if someone requested a different delivery time or wanted to order something different.

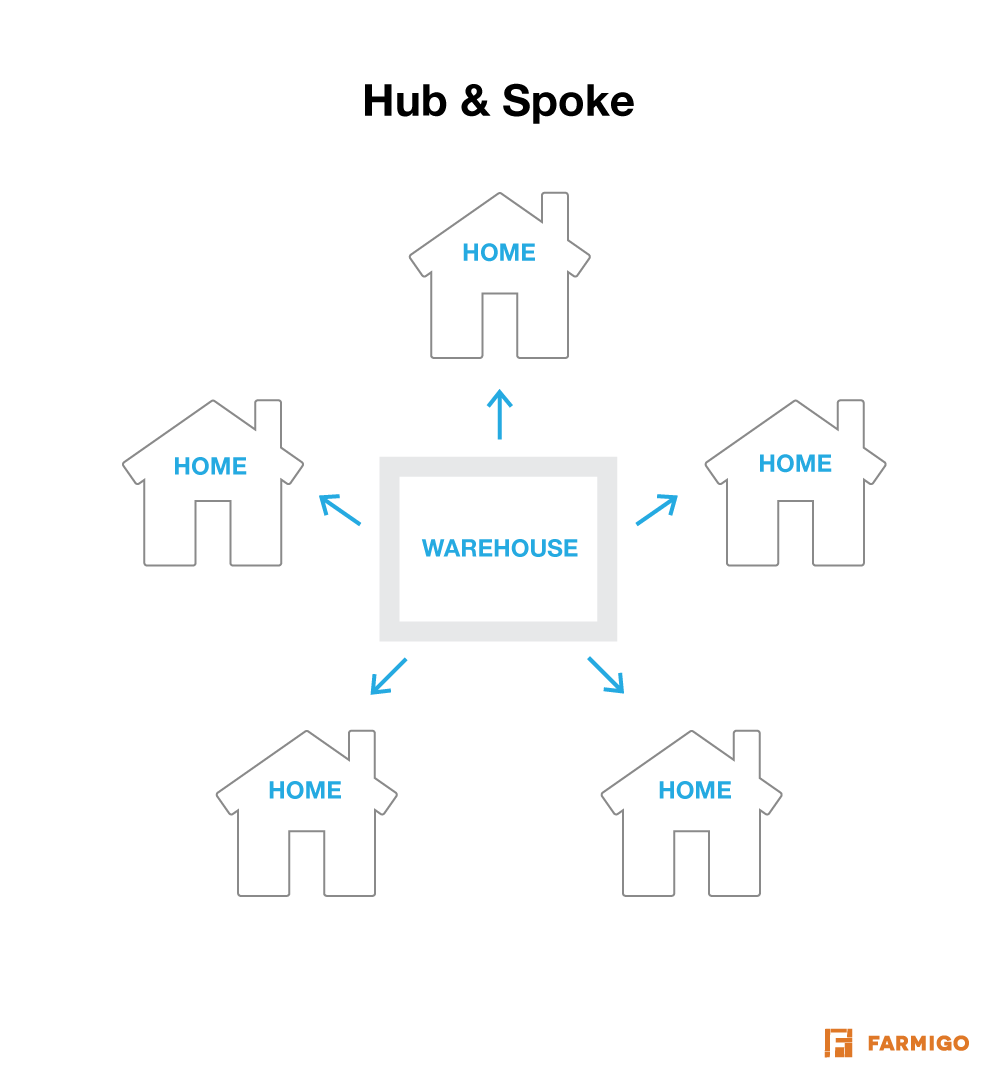

Then there’s the Hub & Spoke model. Everyone from airlines to FedEx to drug dealers have taken advantage of the flexibility that comes with pushing their deliveries through a centralized hub that manages complexity and pushes products out for simple last-mile delivery.

During the peak of the dot-com bubble, Kozmo made headlines for creating an online shop where you could order basic goods like milk, eggs and books for almost instantaneous home delivery. It was the familiar made new: an online ordering system bolted onto a Hub & Spoke system to manage infinitely variable deliveries — but turnaround had to be incredibly fast to keep items like ice cream from melting.

Despite a wave of hype and enormous funding, they imploded under the weight of what proved to be an unsustainably costly door-to-door distribution system. The problem lay in offering low-margin products, inefficient customer-dictated routes and the fact that, from a basic perspective, the world simply wasn’t ready yet — there weren’t any remote controls for placing orders (smartphones), and Internet connection was limited.

Giant companies — and the occasional black market operation — have managed to make home delivery for non-perishables work, but entrepreneurs are still trying to get it right for delivering food. In the last few years, a new wave of startups has arisen, attempting to perfect door-to-door delivery and disrupt the $650 billion grocery market.

Many are utilizing iterations of the Milk Run or Hub & Spoke models, but both face one key problem: Real-world delivery vehicles don’t scale the way digital servers do and, perhaps even more importantly, food needs to be kept at a consistent and safe temperature.

Most of the options (investing in refrigerated trucks, coolers, ice packs and more) are costly, and new and old companies alike are finding themselves burdened by operational costs. Last year, the local food delivery service Good Eggs shut down operations in three of their four regions; Google Shopping Express is shutting down its two delivery hubs; Foodpanda,TinyOwl and Zomato are struggling to manage their burn rates.

Some companies, like FreshDirect, have proven to be successful pioneers in the e-grocery space, but remain unable to expand beyond the metro New York area. Their model begins to fail without the kind of density the largest cities provide.

The traditional giants of the grocery industry — supermarket chains — have only just begun to experiment with e-commerce and home delivery. They’re struggling to justify the investment of time and resources in a relative unknown rather than the safer alternative of simply expanding locations.

When the inevitable transition occurs and we find that the majority of us are ordering our perishables online, supermarkets will find themselves poorly positioned to capitalize on the shift. Stores are too expensive a piece of real estate to serve as a cost-effective delivery hub, and the technological competency necessary to operationalize a direct delivery model simply isn’t there.

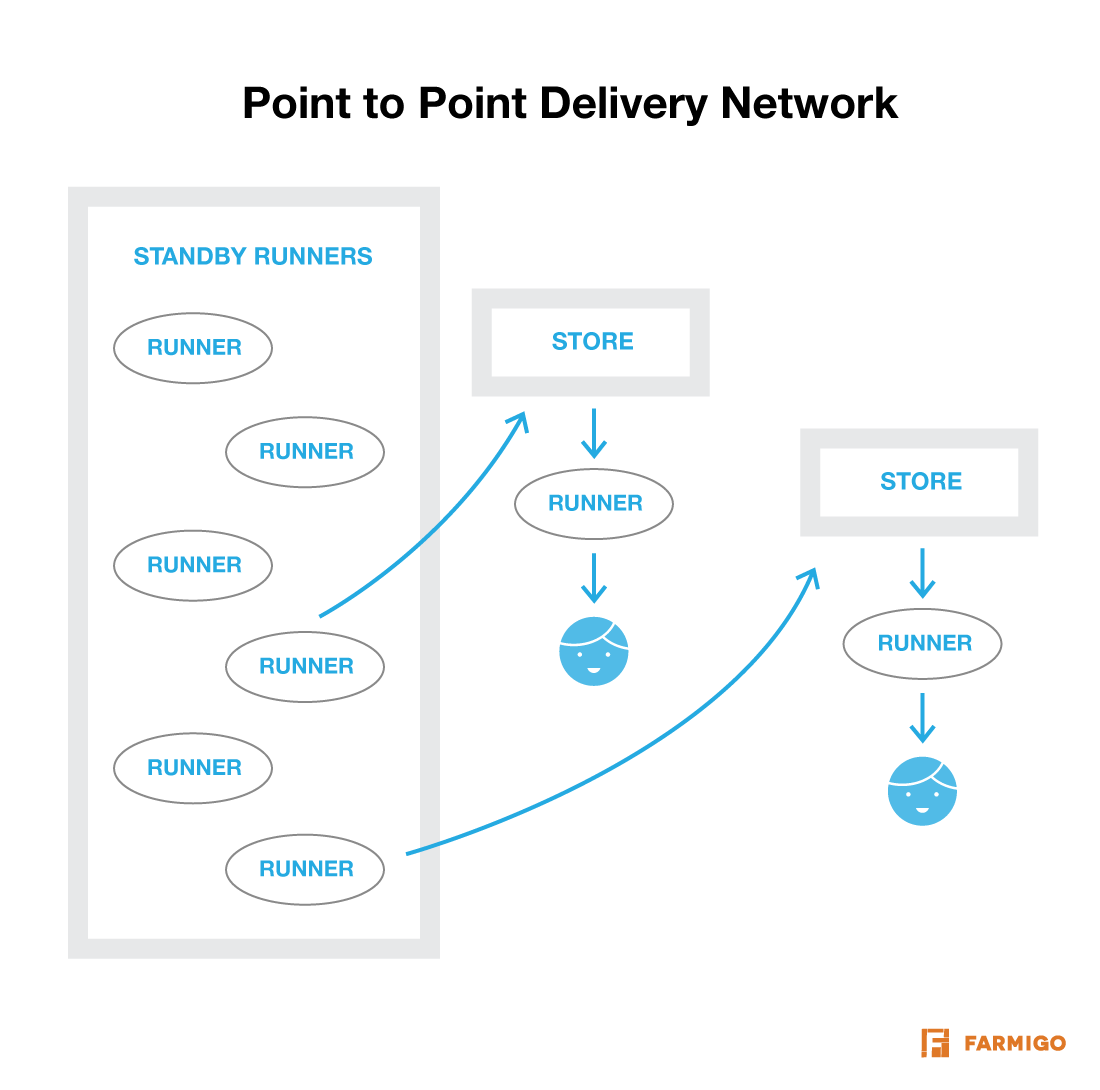

For the startups making the effort, getting delivery costs down to a sustainable level is a matter of lots and lots and lots of deliveries over a very short distance or period of time. There are two new ways to solve this problem: Point to Point and Distributed Delivery Networks.

UberRUSH is a fantastic example of a Point to Point system. Uber has reached enough density with their network of drivers that they can leverage any vacant cars as delivery vehicles, using their tracking information to evaluate which are closest to a given pick-up point. With short distances from point to point, concerns about long delivery runs and food spoilage are minimal.

Unsurprisingly, the cost of this operation is low; these are cars already out and about waiting for passengers, and now some of their downtime can be utilized. Instacart, DoorDash and Postmates are trying to build their own Point to Point systems from the ground up, but it’s unclear whether they’ll be able to raise the über funds needed to build a robust enough delivery network and attain the economies of scale needed to really make a profit.

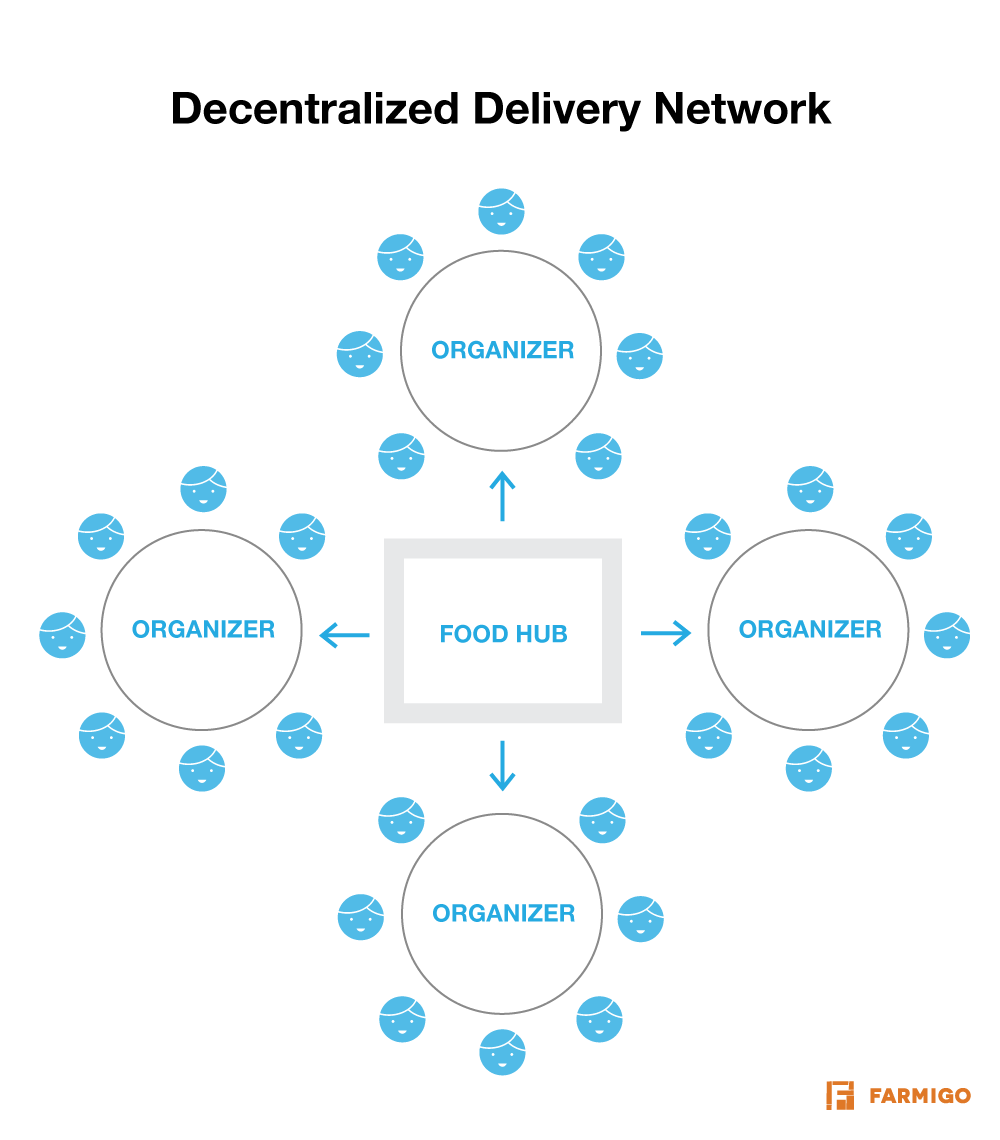

Distributed Delivery Network or “node” models have the advantage of being incredibly cost-effective. Some farm-to-table companies, like La Ruche in France, and Farmigo, the company I founded, are tapping into individuals at the grassroots level to collapse elaborate distribution networks and directly connect farmers and eaters.

We’re partnering with people who are willing to start community pick-up points for customers within their own neighborhoods. This is especially effective just outside metropolitan areas (making this model scalable in ways companies like FreshDirect may never be), where there’s high demand for fresh food (and fewer options) and some of the cost to the company is outsourced to passionate individuals.

Farmigo operates local food hubs that allow farmers and food makers to deliver their products to central locations, where orders are assembled and delivered to the pick-up points, or nodes. The larger the order delivered to each node, the lower the cost per order delivery. It’s a system that has the potential to radically disrupt how we sell and distribute fresh food, and the added bonus of supporting a diversified and sustainable network of small-scale farmers and food makers.

The two models share a lot of similarities. You can think of the cars in Uber’s Point to Point system as smart connected nodes. Most importantly, both allow for fast, flexible delivery without the operational burden of the Milk Run or Hub & Spoke models. There’s still room to grow: We haven’t perfectly optimized the model yet, but there’s huge market opportunity in conquering the inefficiencies of the food space.

Delivery will make or break the winners — it won’t necessarily be the startup with the slickest design, but rather the food entrepreneur who first perfects these newest delivery models. We know customers love to shop, and we know people love to eat… now we just need to give them a way to do both without ever leaving their couch.