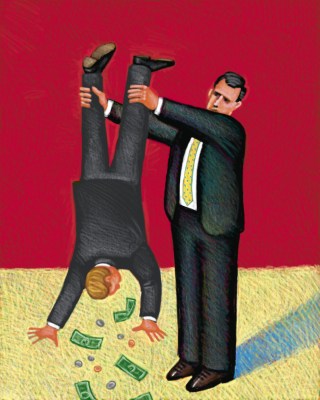

You’ve seen the headlines; you know that over the last couple of years, a growing number of startups has gone public at valuations below where they were valued as privately held companies (or sunk past them quickly).

You’ve also come to understand that a lot of late, and often lofty, private company valuations are getting set by investors who receive preferred shares in exchange for their checks. What that means: those investors receive downside protection in the form of rights to get paid ahead of other investors — or to get paid back more than other investors — in case the companies’ value declines.

There’s a silver lining, though. According to new research out of the law firm Fenwick & West, which has been actively tracking financing terms, of the 41 U.S.-based technology companies that went public either last year or 2014 and that had raised venture funding in the prior three years (life sciences companies were not included), just 20 percent — that’s eight companies — saw these so-called ratchets triggered.

One of those companies was the payment services company Square, which EquityZen cofounder Shriram Bhashyam wrote about here at TechCrunch last November. It’s a very useful example of how this stuff works.

As Bhashyam noted then, the company’s Series E investors paid $15.46 per share for Series E Preferred Stock. The ratchet in Square’s Series E provided that if the IPO price was less than $18.56 per share, the IPO conversion formula would adjust such that the Series E investors would receive a number of common shares equivalent to a number if the IPO price had been $18.56.

Put another way, Square’s Series E investors were guaranteed a 20 percent return on Square’s IPO. Because Square priced at roughly $13 when it went public in November (it’s now trading at $9.23), those Series E investors were provided with millions more shares of common stock to guarantee their return.

That doesn’t sound so great. But Fenwick & West is saying that’s not generally happening as much as you might guess. More, according to its research, while the additional equity given out to shareholders on account of these IPO protections grew “noticeably,” it says, from 2014 to 2015 the effect on the company’s other shareholders wasn’t huge, averaging just 3 percent of the company’s pre-IPO equity.

Indeed, it seems that even the private markets got ahead of the public markets on valuations in some cases, and even though in many of these deals the investors had protections against them sustaining a loss in an IPO, the effect of the protection wasn’t a big problem for the company.

Of course, 41 companies isn’t much of a study sample.

And as you may also be aware, there’ve been no IPOs on U.S. exchanges this month, so we’ll see what happens with the many richly funded companies waiting in the wings.

Even attorney Barry Kramer, who co-authored this latest report and notes to us that things have “worked out pretty reasonably for all concerned” over the last couple of years, adds, a beat later, “At least, so far.”

You can check out the entirety of Fenwick’s survey data here.