The recent announcement that Activision Blizzard acquired King Digital Entertainment, maker of the hit game Candy Crush, for a staggering $5.9 billion is an acknowledgement of the promising (and profitable) future of mobile games.

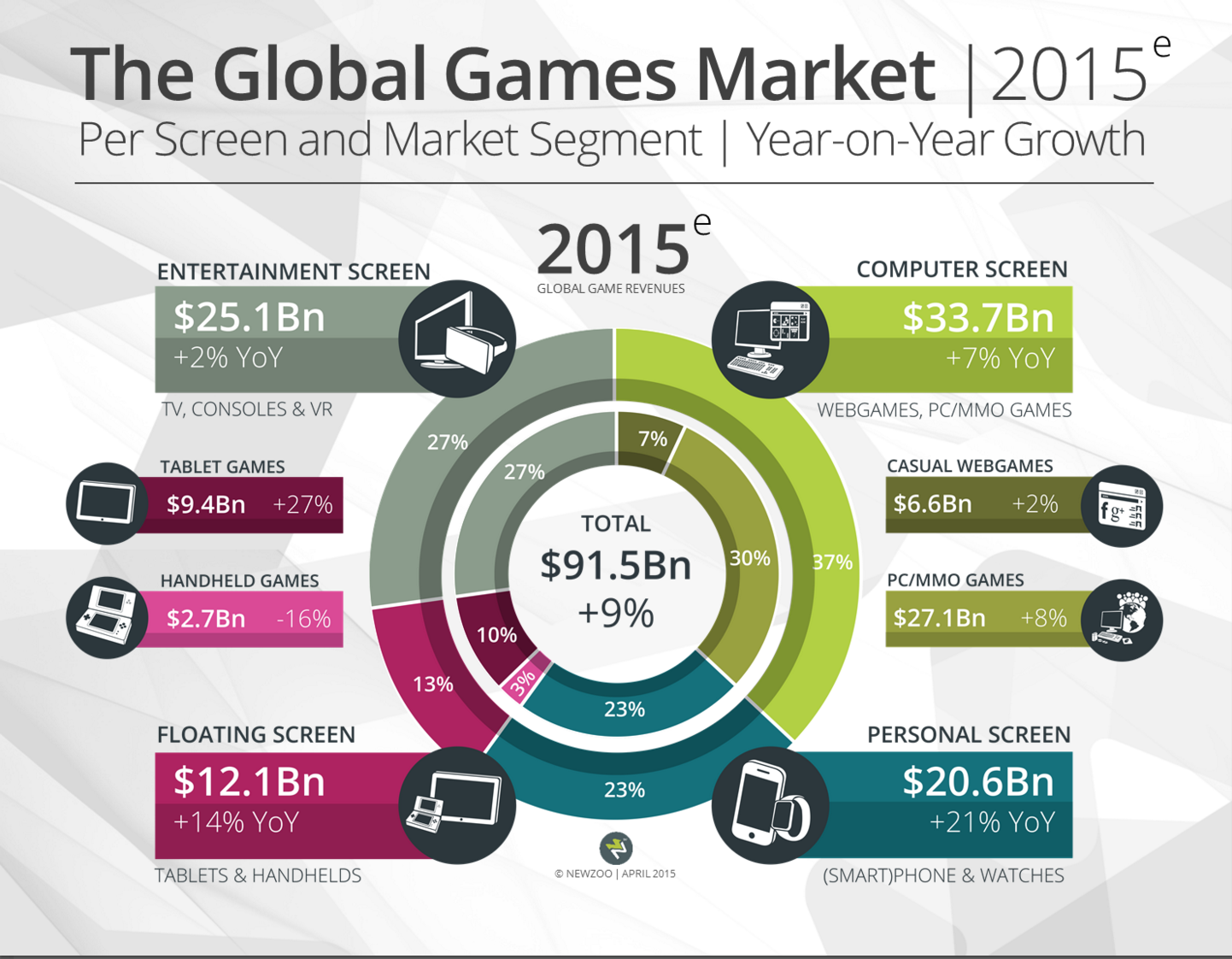

The global gaming market is projected to reach $91.5 billion in 2015. While PC and console games are still mainstream, mobile is the fastest growing segment — increasing 21 percent year-over-year — thanks to the penetration of smartphones in emerging markets and the successful “freemium” revenue model of free-to-play games with in-app purchases. Reports show that users are quick to shell out money for VIP status, virtual items to boost game play or even to win the game at an average spending of $50 per user per game.

Image source: Newzoo, Global Games Market Report 2015

With the market booming so favorable, it is not surprising that online criminals have also found their way into the ecosystem and are creating a thriving underground market for in-game virtual goods. How do they pull this off? Here are a few attack techniques we’ve observed in the wild.

Sybil attacks via proxy servers

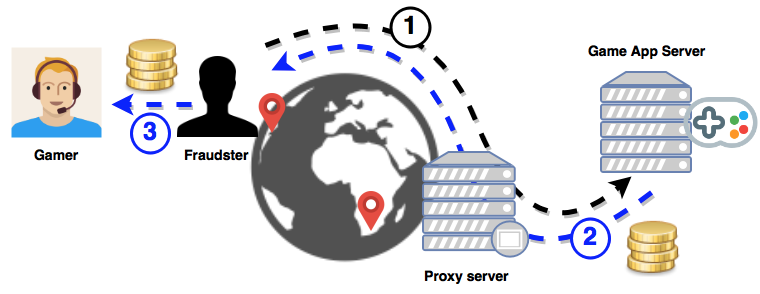

Proxy servers rented out by cloud services allow online criminals to significantly scale up their operations and bypass reputation-based detection systems. In the context of mobile game fraud, they also allow attackers to assume multiple fake identities by simulating presence in different geographic locations, depending on where the servers are located.

These fake identities (or “Sybils” as they are known in peer-to-peer networks) are leveraged to take advantage of game promotions for rare or limited virtual items, such as those that are only given in specific regions or in limited daily quantities.

They are also used to perform virtual currency arbitrage: By simulating presence in different countries, the attacker can purchase virtual goods in one location (the one with the weaker currency), resell them at another location (the one with the stronger currency) and pocket the price difference.

The attacker routes traffic through an overseas proxy server to simulate presence in another geographic location (1), purchase virtual items from the game app (2) and resell to gamers for a profit (3).

These “proxy” servers in different networks and regions are not limited to hosts rented out by cloud services and hosting providers. Attackers also exploit compromised machines located in homes or business DSL networks, such that the malicious activities appear similar to (or intermixed with) those from benign users.

In-app purchase brokers

Some mobile games do not allow virtual items to be transferred between players. In this case, the items cannot be purchased in advance to be resold at a later time, as in the above example.

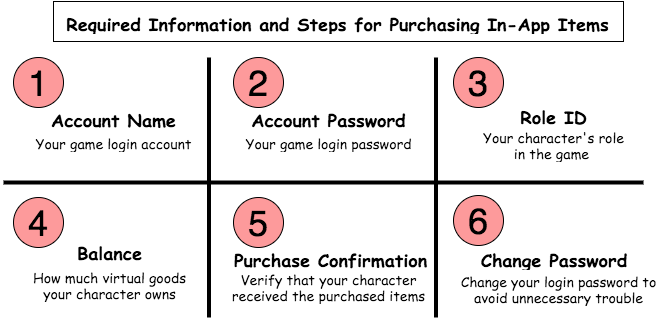

Not to be defeated, online criminals take a different approach with these types of games and virtual item marketplaces. They will advertise price discounts so irresistible — at 25 percent off, or more — that players hand over their game app login credentials to have someone else purchase the virtual items on their behalf. The sellers will even remind you to change your password after the transaction is completed to “avoid unnecessary trouble.”

Instructions from sellers on the underground market for mobile game players looking to purchase cheap virtual goods.

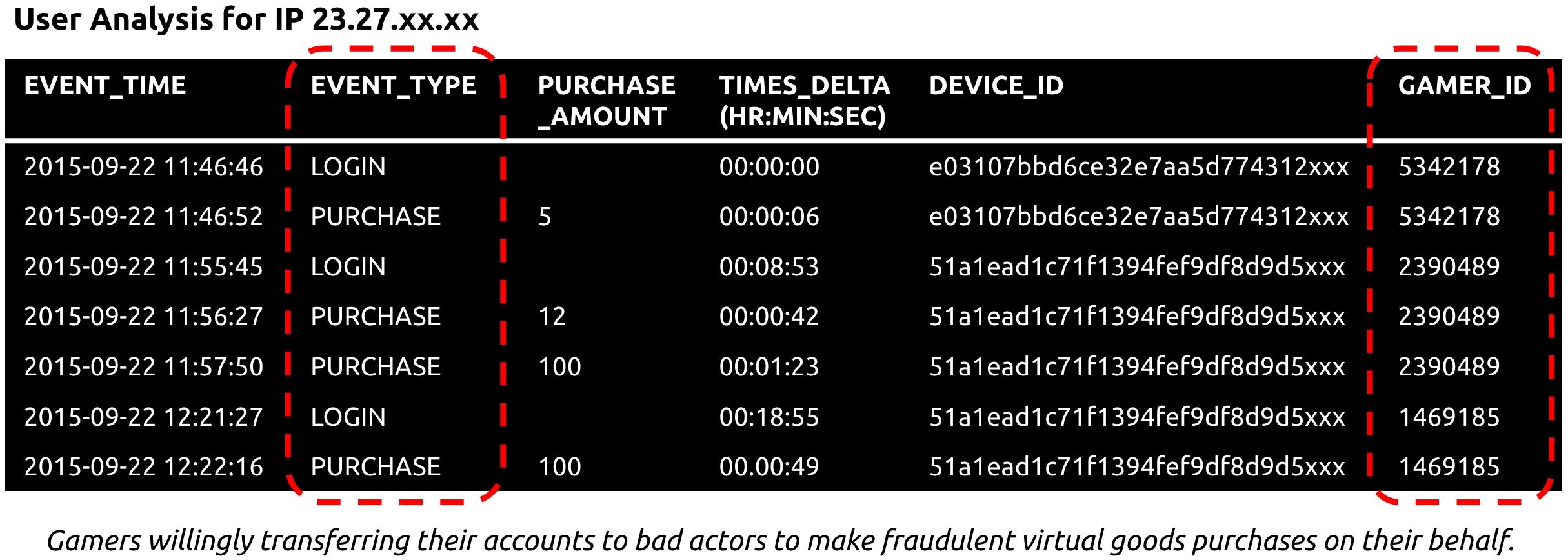

The table below shows an example of this attack in action. Each row corresponds to an event logged by the mobile game app. We can see this attacker repeatedly log on as different users (gamer IDs) to make purchases, without generating any other types of events indicative of actual game play. In fact, each user is only logged in for at most a few minutes — until the purchases are complete.

Fake or stolen credit cards

Nobody would risk being in this business if the pay-off wasn’t good, so how can the underground market offer such steep discounts? It’s back to the source of much financial fraud and headaches in recent years — counterfeit or stolen credit cards from data breaches.

Unlike in-store purchases that can be protected by EMV chip-and-pin technology, game app developers have very limited methods by which to verify an in-app, card-not-present transaction. Existing approaches tend to rely on rules-based systems or supervised learning models, which can only respond to known attack patterns.

To make things more complicated, in-app transactions are commonly mediated by mobile payment platforms, such as Apple App Store or Android Pay, so apps lack visibility into details of the transactions for distinguishing between legitimate and fraudulent purchases.

The real cost of in-app purchase fraud

Why does all of this matter to mobile games? Yes, virtual items don’t really “cost” anything, but this basically means that there is a huge amount of money lost to unrealized gains. It is estimated that for every legitimate virtual item sold and downloaded, there are 7.5 virtual item downloads lost to fraud. This number can be much higher in some countries — in China, for example, there are 273 fraudulent virtual items downloaded for every legitimate item. This means a staggering 50-99 percent of all virtual good purchases are illegitimate.

But perhaps the biggest concern for games is the negative impact on user experience. When fraudulent in-app purchases pollute the economics of the game and allow some players to gain an unfair advantage, it ruins the experience for other players. With the gaming landscape being as competitive as it is today, most players won’t put up with this, and games cannot afford to lose users.

These are only a handful of attack techniques faced by mobile gaming apps, and the full list is not only much longer, but also constantly changing to evade existing detection approaches. As mobile apps rely more and more on in-app “virtual” purchases, they must also be ready to fight fraud. There is a real cost associated with lost virtual goods, and one that has huge negative impact on both user growth and company profit.