CEOs and CFOs of our portfolio companies often ask us, “How aggressive should we be when we set our budget? We want to grow as fast as possible and invest in our exciting new programs. But if we aim too high, we may miss our budget, lose credibility with our board and investors and quickly run out of cash. We know it’s important to under-promise and over-deliver. But if we aim too low, we may grow more slowly, leave the door open for competitors and risk a lower valuation on our next round of financing. What’s the best way to balance these competing goals?”

Based on practical experience with hundreds of early stage companies over many years, we generally recommend the following budgeting best practices. We call it the Bessemer Optimal Budget (the budget), and it involves explicitly recognizing probabilities in budgeting and forecasting.

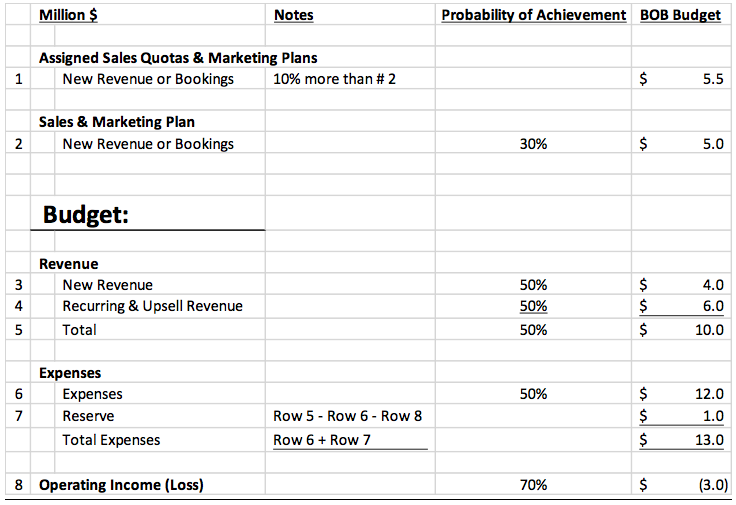

For example, a company can set:

- an aggressive budget it expects to achieve only 30 percent of the time, or

- an “expected case” budget it expects to achieve 50 percent of the time, or

- a conservative budget it expects to achieve 70 percent of the time.

It can then measure the actual results. For instance:

- If a company achieves its budget in 5 out of 10 quarters, it’s achieving a 50 percent budget.

- If 5 out of 10 Bessemer portfolio companies achieve their budgets this year, they’re achieving 50 percent.

In addition, the budget has four components:

- Sales plan and a marketing plan.

- Revenue budget and revenue forecasts.

- Cash budget and cash forecasts.

- Wall Street guidance.

Sales Plan And A Marketing Plan

Revenue consists of new revenue and recurring and upsell revenue.

Fast growth is the lifeblood of venture-backed companies. Fast growth requires new revenue from new customers, new marketing channels, new distribution partners and new products. All of these are risky.

Yet companies must invest in these risky new plans. We want our companies to dream big and to invest sensibly to achieve their dreams, in spite of the risks. Many of our companies reach their impressive goals, and with luck and hard work, some reach goals they never thought possible.

Other companies hit roadblocks along the way: customers delay buying, marketing experiments fail and new products are delayed. We encourage our companies to aim high. Even if they don’t succeed, they often achieve more than they would have achieved with more modest plans. As a result, the sales plan for new revenue, recognizing the inherent risk, has a 30 percent probability of achievement.

Fast growth is the lifeblood of venture-backed companies.

Likewise, for companies where revenue is generated by marketing, not sales, the marketing plan for new revenue has a 30 percent probability of achievement. Companies where both sales and marketing generate revenue will have both a sales plan and a marketing plan.

Sales VPs will often assign individual quotas to their salespeople that add up to 10 percent more than their sales plans. This leaves room for some level of potential underperformance and attrition at the salesperson level. CMOs will often do the same, assigning goals to each marketing program that add up to 10 percent more than the marketing plan.

Revenue Budget

Andy Grove, in High Output Management, points out that in professional sports (which is highly competitive, optimized and measured), 50 percent of the players win every game, and 50 percent lose.

We believe a revenue budget with a 50 percent probability of success, as in sports, is a best practice.

To achieve this, best practice companies start with the sales plan and/or marketing plan, then build in a cushion for unforeseen delays and surprises. Then they add recurring and upsell revenue from existing customers, which is more predictable than new revenue.

Overall, best practice companies set their revenue budget at the “expected case” — in other words, they achieve their revenue budget 50 percent of the time.

Cash Budget

The CEO’s job is to dream big and achieve those dreams. The CFO’s job is to never run out of cash.

It’s usually easier to achieve budgeted expenses than budgeted revenues, but even here, surprises can develop. Important customers may require extra R&D investment and customer support, unexpected employee turnover may lead to extra recruiting, training and temporary employee costs and technology transitions may result in higher costs of operations.

Offsetting this, venture-backed companies often can’t recruit all the high-quality employees as fast as they’d planned, so employee costs may be somewhat under-budget.

The CEO’s job is to dream big. The CFO’s job is to never run out of cash.

A 50 percent probability of achieving the revenue budget, combined with possible expense surprises, creates too much risk for venture-backed CEOs and CFOs, who want to ensure that their cash burn, measured in dollars, and their cash runway, measured in months, at least meets their plan.

Best practice CFOs have a solution for this: the reserve. The reserve is budgeted as an expense line, in reserve for unforeseen expenses or revenue shortfalls. The amount of this reserve should be sufficient for the company to achieve its cash budget 70 percent of the time.

This gives the CFO, CEO, board and shareholders confidence that the company has the cash resources it needs to survive and prosper.

Together, the revenue budget, expense budget and cash budget comprise the budget. This is the plan approved by the board; the company reports monthly and quarterly results compared to this budget.

Forecasting

The budget, once approved, never changes. But the world does change.

Best practice companies build updated forecasts quarterly to account for changes since their budgets were approved. Many companies issue forecasts monthly when conditions are changing quickly. Large companies, such as Oracle, issue updated forecasts weekly as part of their rigorous management practices.

Best practice forecasting uses the same 30 percent/50 percent/70 percent probabilities as the budget, updated with new information. For instance, after Q1, the full year cash forecast will include Q1 actuals, plus an updated Q2-Q4 forecast based on all newly available information and judgments, with an updated reserve to reach a 70 percent probability of achievement.

Bonuses

Best practice sales executives’ bonuses are based on achieving their sales plans. Sales plans will not be achieved every year.

Nevertheless, top quality sales leaders will achieve their plans often enough and, when they do, are likely to be the highest paid executives in the company. Bonus formulas are ramped, so sales leaders are paid well whenever they grow new revenue quickly, even if they fall short of their sales plans.

In much the same way, marketing executives’ bonuses are based on achieving their marketing plans.

Don’t be surprised if you learn your board members have widely varying probability expectations.

Best practice bonuses for other executives and employees are tied to the budget. Often, bonuses are paid 50 percent based on achieving the revenue budget and 50 percent based on achieving the cash budget.

Many companies pay bonuses for achieving specified operating goals, including year-end monthly recurring revenue, customer renewal and upsell rates and customer satisfaction rates.

Often, the cash budget part of the bonus is adjusted to account for extra investments specifically approved by the board of directors during the course of the year.

Many companies pay “above target” bonuses for executives and sales leaders when they achieve “above target” results.

Q4 Optimism Bias

We’ve seen quite a number of budgets with reasonable revenue budgets for Q1 and Q2, with a little extra revenue thrown in at Q3 and a big jump in Q4. After all, companies often budget to ramp up hiring and marketing investments early in the year, hoping they will pay off by Q4.

Companies that achieve their revenue budgets in Q1 through Q3 and miss in Q4 may even feel they’re planning effectively by achieving budget in three out of four, or 75 percent, of the quarters.

Leaders and boards of directors who believe this are deceiving themselves. The most important revenue of the year is the revenue run-rate at year-end, which establishes the base for recurring revenue the following year.

Best practice companies achieve their Q4 sales plans, marketing plans, revenue budgets, expense budgets and cash budgets at least as often as their Q1-Q3 plans.

Bookings

Many companies sign binding agreements with customers in one period which lead to material revenue in later periods. In this case, “bookings” becomes the key metric instead of “new revenue.”

The budget for bookings replaces the budget for new revenue, and has a 30 percent probability of achievement. Likewise, individual sales quotas for bookings total 10 percent more than the budget for bookings.

Wall Street Guidance

As companies prepare to go public, they add another key metric: Wall Street guidance. Guidance is typically more conservative than the budget. According to JP Morgan’s analysis of 203 recent technology IPOs, companies achieved their first and second quarter post-IPO revenue “Street estimates” (which are based on guidance) more than 90 percent of the time.

When Credit Suisse reviewed 534 technology companies that went public since 2005, they found that companies achieved their revenue “Street estimates” 73 percent of the time.

In other words, public companies guide to a 90 percent achievement level in their first year post-IPO, then guide to about a 70 percent achievement level in later years.

Conclusion

We recommend that CFOs explore several budget scenarios with their CEOs — and specifically discuss probabilities of various outcomes.

At first, this may be uncomfortable, because CEOs are paid to be optimistic while CFOs are paid to be pessimistic. CEOs are likely to believe an outcome has a 70 percent probability, while CFOs will have a lower, more conservative, view.

It’s especially important to have the probability discussion with your board. You may even want to survey the board before the discussion, to determine their probability expectations for meeting revenue and cash budgets.

Don’t be surprised if you learn your board members have widely varying probability expectations. If so, it’s even more important to discuss this with your board and to reach agreement on the optimal budget probability for your company.

Sample budget and probabilities