A year ago, I checked in with a tiny non-profit called MissionBit that was bringing computer science education to San Francisco’s public schools after class. Considering that only five percent of the city’s high school students are even enrolled in any computer science classes, San Francisco Unified provides a startling contrast with how the city has become geographic center of the U.S. technology industry over the last five years.

So a San Francisco parent, Tyson Daugherty stepped in. Looking to bridge the city’s school system with the wealth of opportunities of the tech industry all around it, he started MissionBit to bring free after-school computer science education to public school students.

Over the past year, the non-profit has matured. Daugherty has handed over the reins to Stevon Cook, a third-generation, black San Franciscan who grew up in Bayview and ran for school board last year.

Cook has since re-organized MissionBit to bring more students of color into its classes. Today, 23 percent of its students are African American, 25 percent are Latino and 40 percent speak a language other than English at home. For nine out of 10 of them, it’s the first time they’ve ever written code before.

“What Tyson saw in me was someone who had deep roots in the San Francisco community — someone who really cares about expanding the opportunity,” Cook said. “We are going out into the farthest places in San Francisco where you’d never think of seeing a coding class.”

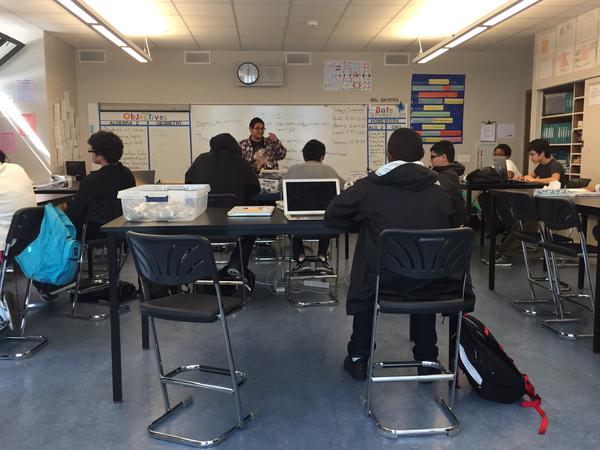

For the first time, MissionBit is teaching a daytime class at Leadership High School in Excelsior on top of the after school programs (pictured above).

When I visited, 15-year-old CJ Carter was building a Zombie apocalypse-themed game. “Everything is so complicated! There’s so much code, like lines and lines,” he told me.

He and his partner, 15-year-old Esteban Colon, were trying to build the pre-loading screen and the main menu.

Cook is also re-organizing MissionBit to be more self-sustaining by having the schools and the district chip in funding for the classes. San Francisco Unified recently passed a resolution to expand computer science education to all grades from pre-school through 12th. But it will take several years given budgetary constraints; California is in the lower half of the rankings for statewide education spending per student. He has a three-year goal of teaching 10,000 students through workshops and courses in campuses and across the entire Bay Area region.

Next up, Cook is also building a six-month programming course for the city’s public housing residents in partnership with Hack Reactor.

“If you can give people the skills to stay in the city and take advantage of all it has to offer, they can escape that generational trap,” Cook said. “When young people get experiences like this, their whole perception of self and their sense of agency is changed. We need to build schools that achieve these things and that help people and their communities advance so they can work for whatever company they want to.”

For Cook, it’s a personal mission. His grandparents came to San Francisco in the 1940s. Like other African-Americans, they were not allowed to buy property anywhere outside of a tiny number of San Francisco neighborhoods because of discriminatory housing policies that barred blacks from purchasing homes in primarily white neighborhoods and suburbs in mid-20th century California.

They ended up living in Bayview. Cook’s grandfather took a job in the shipyards while his grandmother was an admin at the city’s public hospital, the San Francisco General.

“Changed Everything for Me” – A Mission Bit short film from Mission Bit on Vimeo.

Today, the African-American population in San Francisco has rapidly declined over the last generation, falling to 5.8 percent from 13.4 percent in 1970. There is even a documentary being made about the shift, called “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” by Joe Talbot and Jimmie Fails.

Even with record employment growth amid an enormous tech boom, the median income of African-Americans in the city has declined by 5 percent to $29,500. Over the years, Cook has watched his friends and community, which remain in physically isolated neighborhoods and housing developments, get sidelined as the city’s wealth has increased.

“If we can give people better educational and work opportunities and give them possibilities to move up within companies, all of this is worth getting someone out of the projects,” Cook said of his upcoming public housing computer science program. “When you see all of the negative social and emotional risk factors associated with living in those units, you’ll see poorer educational outcomes and higher risks for health issues.”

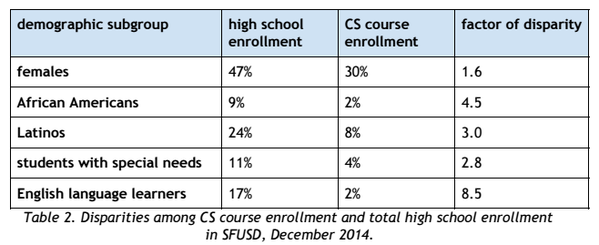

Getting those educational opportunities means overcoming huge discrepancies in access that exist even in the wealthiest of cities like San Francisco. Last year, only 800 kids out of 17,000 high school students were enrolled in computer science classes.

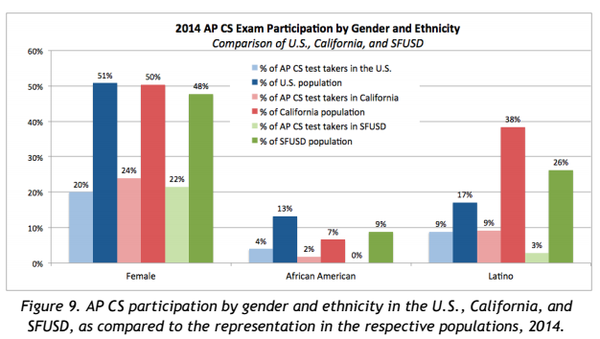

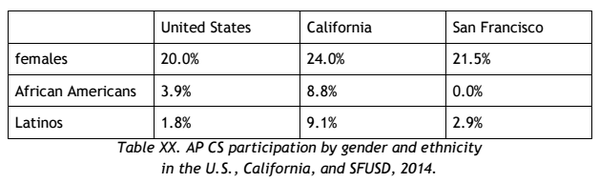

On top of that, no African-American students in the San Francisco’s public high schools took the computer science AP test last year, which is embarrassing considering that the percentage was higher among both state and federal test-takers.

Cook is running MissionBit on a $400,000 annual budget for five lead instructors, computers and equipment. He needs to raise $40,000 by the end of the year minimum in order to keep the program going and is hoping to get to $100,000.

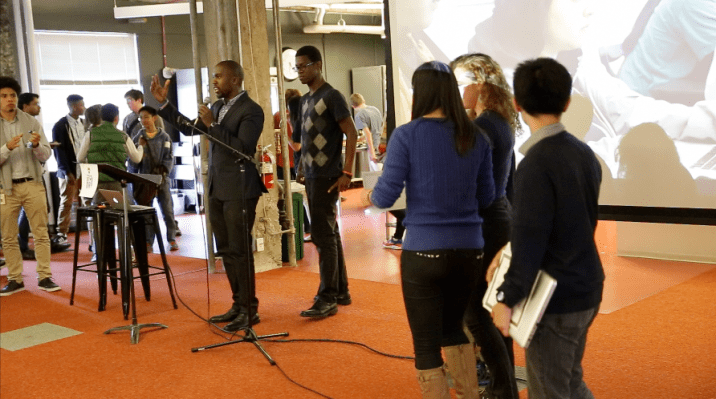

Already, Cook and Daugherty have a couple of well-connected tech leaders on the board like Clive Downie, the chief marketing officer of Unity Technologies. Instagram co-founder Mike Krieger also spoke at the non-profit’s annual fundraiser.

But they still need more funding to keep the non-profit going and they also are looking for volunteer instructors who can commit at least four hours a month to teaching. The classes, which run up to three months, are project-based. So they don’t prefer drop-in volunteers; they need folks who are willing to commit and help the kids complete projects that will be ready by Demo Day.

“At the end of the day, this wealth will come into the city no matter what and it will do what it will do,” he said. “But there are certain things we can do that we can put in place for people who are poor so they can access it.”