Seventeen international human rights and transparency groups, including the Sunlight Foundation, EFF, Free Press, Open State Foundation, Human Rights Watch and others, are taking Twitter to task for its decision to ban the Politwoops tool last month, which was used to track politicians’ deleted tweets. Twitter had earlier banned the U.S. version of this tweet-tracking service in May, saying it was in violation of Twitter’s developer agreement. At the time, Twitter also noted that every user on its service should have the same rights to privacy.

But the organizations argue that what politicians say is a matter of public record, and therefore, they shouldn’t have the same expectations of privacy when using social media as ordinary citizens do.

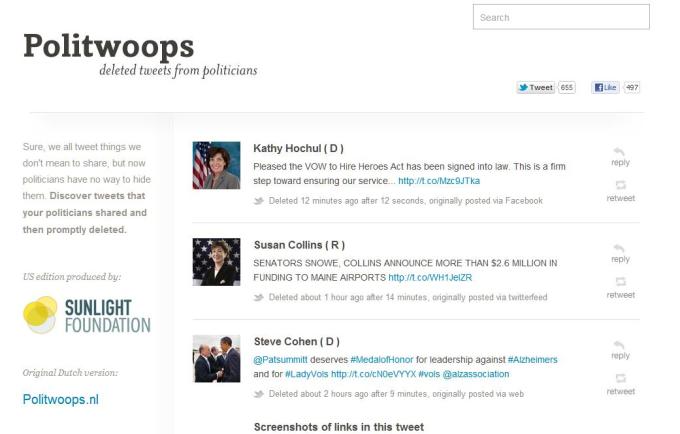

Politwoops, for those unfamiliar, was a tool developed by Dutch organization, the Open State Foundation, over three years ago. The code was used to track politicians’ and diplomats’ remarks on Twitter – and their subsequent removal – in 30 countries around the world. In the U.S., a government transparency group called the Sunlight Foundation used that same code to create a U.S. version of the service.

Twitter shut down the U.S. Politwoops account in May, but dozens of other international accounts continued to operate until this August.

According to Twitter, preserving deleted tweets violates its developer agreement. But in a statement, the social networking company also added that “honoring the expectation of user privacy for all accounts is a priority for us, whether the user is anonymous or a member of Congress.”

Of course, Twitter has the right to run its network as it sees fit, but it’s hard not to believe that the company’s decision is in part influenced by its struggles to grow its user base. Making high-profile public figures uncomfortable, and possibly alienating them from the service by allowing rights groups to shame them thanks to their uncovered deleted tweets, could see them leaving Twitter for good. And with fewer notable accounts to follow, user growth and engagement could also be impacted.

In the jointly signed letter posted today, the rights groups say they recognize that Twitter’s API license allows it to enforce its terms.

“However, Twitter should also take into account human rights when it exercises that discretion—and particularly the right of people to access to information where it serves the interest of public accountability and transparency in a democratic society,” the statement continues. “There are times when what is legal must be outweighed by what is right.”

In other words, the groups are appealing to Twitter’s sense of morality – as if a business where profit is the key goal is motivated such sentiment.

Making their case, the groups also point out that court systems have long-held that public officials don’t have the same expectations of privacy as others, and when politicians turn to Twitter to amplify their views, they’re inviting “greater scrutiny of their expression.” The groups also believe that in the case of Politwoops, citizens’ rights to information outweighs “an official’s right to a retroactive edit.”

In addition, the groups claim that Twitter engaged in very little dialog with the Open State Foundation and the Sunlight Foundation when enacting its decision, which impacted what was a widely used, volunteer-run service. (In fact, Twitter didn’t respond to our requests for comment when we reached last month about the shutdown.)

Twitter also didn’t give the groups a means to appeal or discuss the decision, which the groups’ characterize today as being “arbitrary” and one that “cuts against the very principles of transparency that Politwoops was designed to confront.”

That being said, during its time of operation, Politwoops unveiled very few big scandals involving politicians’ deleted tweets, so it’s hard to calculate the lasting damage its removal will have. After all, politicians do seem to be aware that what they post to social media is meant to be public, and they tend to be careful about what they say. One of the more notable incidents, however, involved politicians deleting their praise for Bowe Bergdahl, a soldier held hostage in Afghanistan, who was later charged with desertion.

The open letter from the groups concludes by urging Twitter to reverse its decision and update its developer policy to make exceptions for information shared in the public interest, such as for transparency or journalistic purposes.

What’s most interesting about this incident, is that Twitter has often been thought of as a tool used by citizens worldwide to take social and political action. The “Twitter Revolution,” for example, is a term that refers to how demonstrators used the social network to plan protests, mobilize citizens and disseminate political news. It has been used in a number of protests and revolutions, including the “Arab Spring” – something that Twitter itself has acknowledged, and perhaps even reveled in.

For example, in 2015, Twitter’s then-CEO Dick Costolo wrote about Twitter’s ability to offer people access to information at scale, and that power that holds:

“It means that a country can hold its government to account and that it’s harder to cover up the true version of events. It won’t end the use of propaganda, of course, but giving people direct access to information, and the ability to share and discuss it openly, provides a very strong counter balance.”

The decision to ban Politwoops, then, seems to fall very far from Twitter’s ideals.

The seventeen groups who signed the letter, posted here, include Alternatif Bilisim (Turkey), Art 34-bis (Italy), Asociacion por los Derechos Civiles (Argentina), Bits of Freedom (Netherlands), Blueprint for Free Speech (Australia), Derechos Digitales (Latin America), Electronic Frontier Foundation, Free Press, Human Rights Watch, Jinbonet (Korea), OpenMedia International (Canada), Open State Foundation, Paradigm Initiative (Nigeria), Pirate Party (Turkey), Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales (Mexico), and Sunlight Foundation (U.S.)