U.K. startup Neurence, which has previously released two proof-of-concept apps showcasing its augmented reality tech, called Taggar and Tag Me, has now launched its long term platform play: a machine learning cloud platform for object recognition which it’s hoping will underpin the next wave of search queries as computing becomes increasingly immersed in the physical world — thanks to the rise of wearables and the Internet of Things.

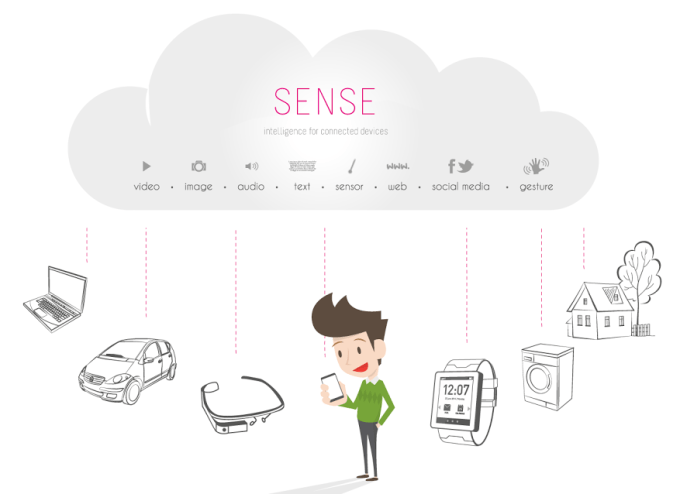

It’s calling this platform Sense, and is offering free access to interested developers via an SDK as it seeks to drive adoption and usage. It needs users because there’s a crowdsourcing element to the platform play, with individuals encouraged to add objects to the Sense database themselves to help build it out and make it more useful and contextual.

At launch there are “hundreds of thousands” of recognized objects but the Sense system is capable of identifying up to five million, according to Neurence investor Dr Mike Lynch — investing via his Invoke Capital technology investment fund. Some types of objects, such as books, have been able to be added in bulk, by crawling online datasets. But to scale up to the level of adoption the startup is hoping to achieve, the platform is clearly going to need lots of humans feeding it data.

As Wikipedia has crowdsourced an online encyclopedia, Neurence’s hope is enough users will help it label and augment millions of real-world objects — so it can become a contextual layer for the Internet of Things over the next five+ years.

“The important point here is that the devices, the wearables that are out in the real world have full context, because they can see and hear [via Sense],” says Lynch, in an interview with TechCrunch. “Anyone can tell the system about a new thing. It’s not something we need to program. All you need to do is look at something and rather like Wikipedia you can contribute that object and its properties to the cloud and it’s then available to everyone.”

“You can author and you can use, and it’s available to anyone on the system,” he adds.

Given that objects can mean very different things to different people, groups, communities and cultures, Neurence building a platform that affords users the ability to author an object’s context is the sensible decision. Users can upload images, audio files and algorithms to the platform via the Sense website to give a real-world thing their own digital spin.

The Sense platform works by analyzing what can be seen and heard around a connected device — using its camera and microphone (if it has both; the platform can also work with just one or the other input) — and turning the sensory data into “probabilistic vectors”, as Lynch puts it, sending those to its cloud engine for processing. So it’s not streaming or uploading any feeds of actual visual or audio data into the cloud (because that would be really slow, as well as really creepy).

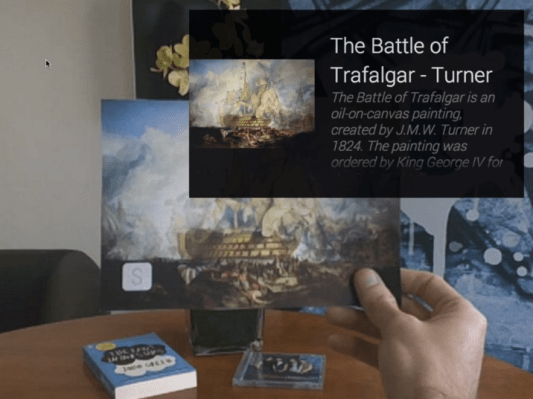

The platform then identifies real world objects if it finds a pattern match in its database, and can do so in near real-time (depending on the hardware being used). Objects it can recognize include signs, books and paintings.

But that’s just the initial utility for Sense. The act of recognition opens up follow on actions for the user, much like a returned search on the desktop invites a user to engage with a spider’s web of additional information. With Sense the device wearer can also quickly access additional information and content about an object in their vicinity. This can be content that the system or developer has associated with a particular object, or which a user has custom-tagged for their own eyes or for others.

“One of the things that anyone that writes an app or a piece of code that goes into an object can do is say ‘I want this recognized and if you have definitions from these sources they take priority’,” says Lynch, discussing how different services and users could implement and customize Sense to fit their world view.

“What you might expect is various sub-cultures would have their own definitions of things,” he adds.

Hunting for the next generation of search

If all that sounds a bit layered and nuanced for mainstream utility, the core problem Sense is aiming to fix is a simple one, according to co-founder Charlotte Golunski. “We see this as the next generation of search,” she says. “It’s exactly the same reason we use a search engine.

“We want to find out more about things. We want to learn about similar things we might like. We want to know the background about something. Often I’ll be walking along and I’ll think ‘oh, what’s that building? What’s the history of it?’ Or I’m in a foreign country and I want to understand what the foreign text is I’m seeing. And all these things could certainly be solved by the advent of smart wearable devices.

“I’m often wondering more about the things I’m looking at and this is a way to just access that information very, very quickly and discover more about something without having to get my phone out, search for it, go down a list of links. I can just instantly access information in a much more human friendly way, as if I would ask a friend when I was walking along… That’s the problem that we’re trying to solve here.”

The Sense technology can support facial recognition but Neurence is targeting objects rather than people at this point, given the massive privacy can of worms that automatic, real-time facial recognition technology inevitably opens up. (More on the privacy implications of Sense below.)

After successfully identifying an object with Sense, a user is able to follow up with a series of configurable actions — such as purchasing the same item via an ecommerce store, or playing a video associated with it and turning a movie poster into a trailer they can watch immediately, for instance. This is where Neurence sees the likely future monetization of the Sense platform — such as via affiliate or promoted links. (Albeit generating revenue is very far from its mind at this early point.)

As mentioned above, these actions can be customized by the user to fit their own needs and tastes. One example might be to have a wearable device pull up real-time transport data when it perceives its wearer has arrived at their local bus stop or train station to save them having to fire up an app and check this manually.

It’s up to developers how they apply Sense in their apps and devices, so applications are going to vary. Golunski says early developer interest has focused on shopping use-cases and real-estate scenarios, such as turning pictures of houses into dynamic tours.

Neurence is already working with Google on a Glass application of the Sense technology, and also with Samsung for its Galaxy Gear 2 smartwatch (which has a camera). Neither application is out in the wild yet but both were shown in action to TechCrunch. It’s working with around six device developers in total at this early point, and says it’s keen to get more on board.

The Galaxy Gear 2 application of Sense allows the user to point the device’s camera at an object — such as a book — and once/if the system recognizes it a red dot appears at the top corner of the screen. Tapping on that brings up information about the item and a series of actions that let the user drill down further or purchase the item.

The Glass application, which can be seen demoed in the below video, allows the wearer to get related information about what they are looking at pushed to the display. They can then use additional voice commands to interface with Sense via Glass and access other digital content associated with the recognized item.

Neurence was founded last year but its algorithms and underlying machine learning tech predate that by some time. Its co-founder, Dr James Loxam, studied at Cambridge University, and set up the company to commercialize his machine learning PhD research. The startup has been backed by $4 million in investment from Lynch’s Invoke Capital (who also has his own PhD pedigree in computer vision technology). Neurence’s other co-founder, Golunski, is a former Autonomy employee.

Lynch says developments in computer vision and machine learning mean the ability of computers to recognize objects in real world environments has made leaps and bounds in recent years. Using a camera that can be directed by the user on the particular object of interest — as in the Sense scenario — also helps make the recognition task easier. Plus the technology has been given uplift by improvements in mobile hardware, so more processing power and higher quality cameras with auto focus and image stabilizing tech.

On the demand side, there’s evidently a way to go to get users engaged with an object recognition search platform, given how nascent wearables still are — and with text and typing remaining the major focus for mobile digital activity.

But Neurence’s pitch is that the proliferation of connectivity, wearables and connected objects will create more demand for an alternative interface for search querying the world around you — one that does away with the friction of manual inputs. And that’s where Sense aims to insert its smarts. (Other startups are also clearly investigating the intersection of computing and the physical world; Magic Leap springs to mind.)

“This is a long term thing,” says Lynch. “You can imagine objects are all going to have this intelligence. They’re going to have to be able to use this and exchange it with each other. This is a fundamental part of the next generation of the Internet. So we’re having to take some bets. We’re betting that always on connectivity will arrive. We need that, there’s no doubt about that — but I think that’s a fairly safe bet on the timescales that we’re looking at.”

“What you’ve seen [in the Sense demo] is rather like seeing the first television pictures in the 1940s but I think things like cameras, resolutions, all that sort of stuff, one can be fairly sure are going to get better on these devices,” he adds.

Lynch envisages an early wave of applications will use Sense in specifically targeted ways, such as the smartwatch application with its focus on shopping. Followed by next-gen smart glasses that are a lot more polished and useable than the “clunky” current crop of devices — and therefore more likely to be more widely adopted. Beyond that, over the next five years, he sees potential for demand to blossom as the universe of connected objects populating the Internet of Things inflates and having more intelligent interfaces becomes an imperative.

“You’re going to have a lot of intelligent objects and they’ve all going to have to deal with this problem and exchange their understanding with each other, and that’s really where this idea starts to really come into its own,” he says, describing Sense as “an incredible enabler” for the next generation of smart systems.

“If you want a system that knows whether your grannie has fallen over in her house it’s got to be intelligent to work. If you want a system that is going to reduce accident breaks because autonomous cars work in reality then you have got to these kinds of intelligences,” he adds.

Little Brother’s prying digital eyes

But there is one other big bet to consider: that people will be comfortable with the privacy implications posed by widespread application and adoption of adaptive, real-time recognition technology.

Early reactions to Google Glass suggest many people are in fact highly uncomfortable with visible surveillance wearables. Whether that discomfort wears off as wearables proliferate remains to be seen.

We are now going to enter a world where the ability [of technology] to understand becomes industrial

Sense offers connected objects a real-time ability to understand what’s going on around them — and so there are obvious and potentially seismic implications for privacy should this sort of technology become pervasive, especially if facial recognition is switched on (as it has currently been toggled off).

Put such a technology in the hands of lots of people and it’s not Big Brother watching you; it’s Little Brother, says Lynch — and Little Brother really is everywhere.

“In a world where you’ve got the ability as a user to instantaneously look up things, in effect, with no effort, and your ability to, for example, know what’s going on around you, among other people who are around you, does go up a lot…and that does raise some interesting questions,” he says when I pose the privacy question. “It’s not dissimilar to the problem where we can all get very excited about having CCTV cameras in town centers but as long as no one’s watching them and no one can analyze and follow them and all that sort of stuff it’s much less of a problem.

“But when you start to see these machine learning technologies that can understand what’s going on in one camera and as the person walks to the next camera understand that, and then yes there are some questions that society is going to have to look at — at how it wants to handle that sort of thing.”

Lynch concedes there is a big societal debate looming here. But he also argues that the networked technology is already inexorably being slotted into place — so it’s just a question of how we use it now. Sensing technologies are coming regardless, even if Sense is not the platform that prevails.

“The thing people haven’t really understood about the privacy debate is… we are now going to enter a world where the ability to understand becomes industrial. So that will raise questions and there will have to be thinking about that, and how that’s done,” he says. “We’re going to have to work how we want powerful technologies to work in this area.

“The genie is out of the bottle on this. It is happening. Everyday there are apps coming out that are more intelligent and understand more what’s going about them… the thing that people have missed is it’s not just the power of an individual app on an individual phone but when you network that through social media and you have 3,000 of them in a city, then you get a data fusion effect, which is very powerful.”

“My position is not to make a value judgement here. I’m not saying that’s good or bad, you can argue both cases, but it is inevitable,” he adds.