Europe’s Article 29 Working Party, the body comprised of data protection representatives from individual Member States of the European Union, has now published guidelines on the implementation of the so-called ‘right to be forgotten’ ruling, which was handed down by Europe’s top court back in May.

The European Court of Justice ruling gives private individuals in Europe the right to request that search engines de-index specific URLs attached to search results for their name — if the information being associated with their name is inaccurate, outdated or irrelevant. The ruling does not generally apply to public figures, so requires search engines to weigh up requests against any public interest there might be to accessing the information in a name search de-listing request.

Earlier this week the 29WP said it wanted the search de-listing ruling to extend to cover results on .com domains, not just European sub-domains. However Google, the major search engine in Europe, has been implementing the ruling only on sub-domains so far. So it remains to be seen whether the company will follow the guidance and extend de-listing to .com as well.

Up to now Google has argued that .com is not much used in Europe and therefore it’s not relevant to the ruling. But not implementing de-listing on .com offers a trivial workaround of the law, as the 29WP guidelines note. TechCrunch has asked Google whether it will expand its implementation of search de-listing to cover Google.com and we will update this article with any response.

Public interest balance

The 29WP guidelines cover multiple aspects of implementing the ruling — beyond expanding it to cover .com domains — and expend a lot of ink stressing the importance of balancing any public interest in accessing information up for de-listing.

The guidelines note (emphasis mine):

…a balance of the relevant rights and interests has to be made and the outcome may depend on the nature and sensitivity of the processed data and on the interest of the public in having access to that particular information. The interest of the public will be significantly greater if the data subject plays a role in public life.

They also assert that any impact on freedom of expression and access to information is “very limited” exactly because of this public interest balancing act. (Again, emphasis mine.)

In practice, the impact of the de-listing on individuals’ rights to freedom of expression and access to information will prove to be very limited. When assessing the relevant circumstances, DPAs will systematically take into account the interest of the public in having access to the information. If the interest of the public overrides the rights of the data subject, de-listing will not be appropriate.

The context here is that free speech advocates, such as Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales, have been hugely critical of the ruling — dubbing it ‘censorship of knowledge’. Views which inevitably butt against the principles of European data protection law.

The law in Europe affords private individuals a degree of control over the processing of their personal information — hence the ECJ ruling expanding existing DP legislation to cover search engines after deeming them data controllers whose algorithms do in fact process personal information.

Critics of the ruling have also questioned how a public figure can be defined. A second section in the 29WP guidelines includes a list of common criteria intended to be used by data protection authorities when handling appeals for search de-listing requests that have been refused by search engines. And this list includes steerage on what types of individuals can be said to have a “public life”.

It also stipulates there is an “argument” in favor of the public being able to search for “information relevant to their public roles and activities”. That suggests that while a private individual’s private life naturally falls within the parameters of search de-listing, details associated with a private individual’s working life or involvement in a wider community may not.

The criteria notes:

It is not possible to establish with certainty the type of role in public life an individual must have to justify public access to information about them via a search result. However, by way of illustration, politicians, senior public officials, business-people and members of the (regulated) professions can usually be considered to fulfill a role in public life. There is an argument in favour of the public being able to search for information relevant to their public roles and activities.

A good rule of thumb is to try to decide where the public having access to the particular information – made available through a search on the data subject’s name – would protect them against improper public or professional conduct. It is equally difficult to define the subgroup of ‘public figures’. In general, it can be said that public figures are individuals who, due to their functions/commitments, have a degree of media

exposure.

The document also notes that some information about a public figure may actually be “genuinely private”, and would therefore qualify for de-listing — information such as their personal health or about their family members. “But as a rule of thumb, if applicants are public figures, and the information in question does not constitute genuinely private information, there will be a stronger argument against de-listing search results relating to them,” it adds.

Problems with Google’s implementation

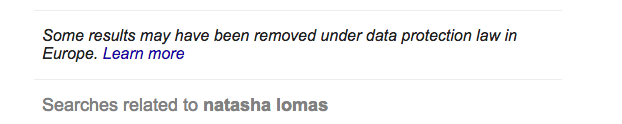

In addition to picking up on the .com problem, the 29WP guidelines also tackle two other issues that have caused issues with the current implementation of the ruling: firstly Google’s practice of routinely posting a notice at the bottom of search results for private individuals’ names informing users that some information may have been removed.

E.g.:

The 29WP notes that this practice “is based on no legal requirement under data protection rules”, and further notes it “would only be acceptable if the information is presented in such a way that users cannot, in any case, conclude that one particular individual has asked for the removal of results concerning him or her”.

So, in other words, Google must either not post these notices at all, or must post them universally under all name searches in order to avoid web users being able to infer a particular person has made a de-listing request.

(Incidentally it is not at all clear what current logic Google uses when choosing to display these notices, although it has previously said it does not display them on searches for celebrity names. In the case of my name, I have not personally made any search de-listing requests, however it may be the case that another individual with the same name has. Or not. It’s not clear what Google’s current criteria is for these notifications.)

The 29WP also tackles what has been a clear problem with the current implementation of the law by Google — namely a ‘Streisand effect’ caused when it has informed source websites that some of their content has been de-listed for a particular search — and those sites have then informed their users.

On this point the guidelines state that it should not in fact be routine for search engines to inform webmasters of pages affected by de-listing requests — stressing “there is no legal basis for such routine communication under EU data protection law”.

Yet Google has been routinely informing websites when their content has been de-listed. And by informing webmasters in this way the company has easily been able to whip up a media storm of ‘censorship’-based criticism, which aligns with its objections to Europe’s data protection legislation — and allows others to lobby against the ruling on its behalf.

Where news outlets have covered specific de-listing requests the result is to re-insert whatever information an individual was requesting for de-listing back into the foreground of the public domain. So instead of obscurity, the result is fresh publicity — the opposite effect to that intended by the ruling.

The 29WP guidelines further clarify that contacting the original editor of the content being targeted by a search de-listing request might actually be appropriate in some cases when more information is required to make a decision — so prior to de-listing, not after the fact. Which is not how Google has been operating thus far.

The guidelines also made a call for search engines to be more open about the criteria they are using to make de-listing decisions. Again, Google has only released limited and very partial information about how it makes de-listing decisions thus far, focusing most of its energies on lobbying against the ruling — including by organizing a public tour of Europe to debate the underlying principles.

The 29WP guidelines add:

Taking into account the important role that search engines play in the dissemination and accessibility of information posted on the Internet and the legitimate expectations that webmasters may have with regard to the indexing and presentation of information in response to users’ queries, the Working Party 29 (hereinafter: the Working Party) strongly encourages the search engines to provide the delisting criteria they use, and to make more detailed

statistics available.

TechCrunch has asked Google for comment on the guidelines and will update this post with any statement.

The full 29WP guidelines document is available here.