Forget.me, an online service for Europeans wishing to submit de-listing requests to search engines asking for outdated or irrelevant personal information to be de-indexed, has put out new details of the nature of requests it is helping to process — shining a little more light onto what remains a relatively closed-box process at this nascent stage.

The operational darkness here is mainly because the so-called ‘right to be forgotten’ (rtbf) court ruling, which requires search engines to accept and process de-listing requests from private individuals, is so new, only being handed down back in May (even though the data protection legislation it references dates back to 1995). Ergo the various players are still working out the details of how the ruling is best implemented.

The ruling requires Google and other search engines to accept and process requests from private individuals wanting old/irrelevant/inaccurate information de-indexed from a search for their name. It requires that search engines, as data controllers, balance considerations of an individual’s right to privacy with factors such as whether that individual has any public role and therefore whether there might be a wider public interest in continuing to surface to whatever personal information they are seeking to obscure.

NB: Europeans wanting personal data de-listed from Google do not need to use a third party service, such as Forget.me, but can make a request directly via Google’s web form.

Forget.me’s parent company, Reputation VIP, put out some earlier data — in June — on requests being submitted via its rtbf hand-holding service. At that time it had garnered 13,000 registrations, with 1,106 of those users having submitted right to be forgotten applications — requesting the removal of a total of 5,218 links.

It’s latest data records some 21,000 registrations for its service three months after launch, and 15,061 URLs submitted to Google via Forget.me from 30 different countries.

Looking at the submitted URLs, Reputation VIP notes that the majority (56%) have not yet been dealt with by Google. Of the 44% that had received a response, a majority (59%) had had their de-listing request denied by Google. Just over a third (36%) had had a de-listing request granted at that point, and a marginal 5% had been asked to supply Google with more information so it could assess their request.

The company points to a shift in Google’s decision making since the rtbf request process launched, based on tracking its week by week decisions — noting that Mountain View was far more likely to grant a request made in the first week of the process vs the start of September.

According to its data, 57% of rtbf requests submitted using Forget.me were initially granted by Google in June vs just 28% granted in the first week of September. (Of course the nature/type of requests Google has received may also have changed over the three months.)

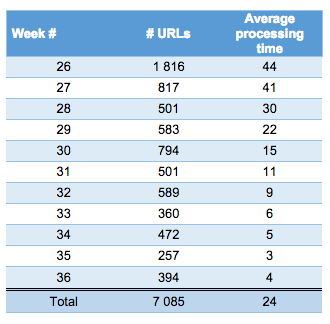

It has also tracked the average time taken for a decision over this period — and notes it has decreased significantly, as you might expect with a new process being established, from a whopping 44 days on average at the start of the process to just four days by early September. The data also indicates that Google has typically had to process fewer URLs as time has gone on, lightening its rtbf workload.

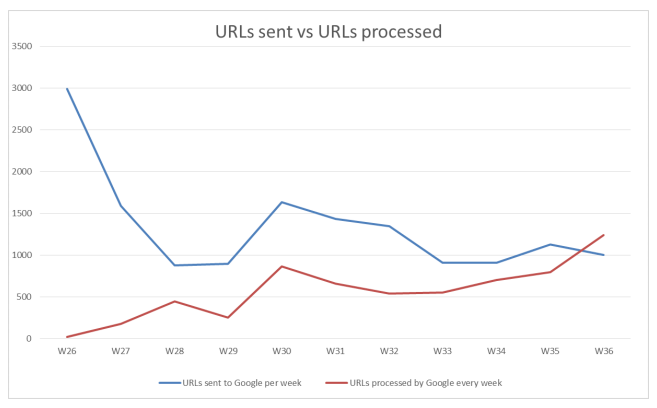

Google was evidently initially swamped with requests, and had to work its way through a backlog. But it’s now processing more requests than it receives per week, according to Forget.me (see graph below).

All of which suggests Google was perhaps not being so rigorous in assessing the merits of initial requests, in the interests of quickly cutting through the backlog in order to get on top of the process — but has since, perhaps, tightened up its assessments, now it’s not facing such a mountain of requests. (But again, it’s difficult to make a definitive judgement without knowing the content of the requests being processed, and how their complexity may have changed over nature.)

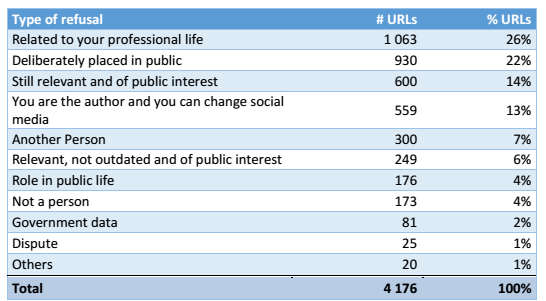

Where applications have been refused, Reputation VIP has collated the types of refusals individuals received from Google (listed in the table below).

The most common reason for refusal thus far (accounting for 26% of refused URLs) was that information related to the submitters’ professional life. Next most common was that it had been deliberately placed in public (22%). Thirdly Google’s refusal was based on info still being ‘relevant and of public interest’, in its view.

Determining who exactly has a public role and who does not should be a key part of the assessment process for Google et al to determine when a de-listing request for individual privacy is fair and should be granted vs when it’s in the public interest not to obscure a piece of information so a request should be refused.

Where refusals were based on the submitter having what Google determined as a ‘role in public life’, Reputation VIP checked the listed professions — and found the following job types coming up, shining some light on how Google is making these public role assessments at this point:

- TV presenter

- Journalist

- Politician

- Business leader

- Famous artist

Where rtbf requesters were asked to supply Google with more information in order for it to process their de-listing application, Reputation VIP said the most commonly asked questions were on the following topics:

- Does your request concern a pseudonym?

- You have made an error in your request, can you correct it?

- Can you prove your link to the country concerned?

- Why is the URL inappropriate or no longer relevant?

- Can you prove you are not guilty of what you were accused of?

- Can you prove what you were accused of is no longer relevant?

The wide scope of some of the above questions hints at the complexities involved in making decisions based on individual arguments — complexities which Google is having to grapple with under European data protection law.