Editor’s note: Ben Maximilian Heubl, is a tech blogger, a data journalist (data journalism ambassador for Infogr.am), digital health geek and technology advocate and speaker. Ben founded a European chapter of the non-for profit organization Health 2.0 and currently advocates for improved online health access via Zesty UK.

How interested is your doctor in health data that you’ve tracked yourself?

Wearable health and fitness devices are now hugely popular, and they certainly appeal to people who want to tot up their paces. But many people who have invested in trackers like the Fitbit, Jawbone’s UP bracelet, or the Nike+ FuelBand want to know: Can this data be used to give me more serious healthcare insight? Could it help my doctor to give me better advice?

There’s certainly going to be no shortage of raw data. With tech giants Google, Amazon and Samsung heavily committing to this space, ever more wearable health devices are going to be connected to your life. Samsung’s Galaxy S5 smartphone, for example, has a built-in heart-rate sensor, a pedometer feature, and the S Health app.

Apple, meanwhile, recently announced HealthKit, an expression of intent to take the tech war in health to the next level with a platform that, rather like the App Store, will support lots of independently created applications in tracking health and wellness.

But does that mean we’ll soon walk into our doctors’ office and find that the first thing they want to see is our statistics?

Dr. Dush Gunasekera, Co-founder & Director at the myHealthcare Clinic in London thinks so. He said he hopes that wearable health technologies will help doctors to work with patients more effectively, leading to better treatments and outcomes.

“In our clinic, we welcome and embrace innovation and online health access,” says Gunasekera. “Generally the more accurate data we have on our patients, the better we can help with their health problems. Sometimes a snapshot can be just enough to give us the indications of a problem, or to prevent us missing one. Systems like Apple’s HealthKit might be one of the answers to providing a better patient-doctor partnership. Also in our job, timing is everything and the more the patient supports our work, the more we can provide better treatment and advice.”

However, Gunasekera and other medical professionals also see challenges that will need to be solved if wearables are going to achieve credibility with the medical profession:

Accuracy is a big problem. Samsung’s tech has been shown to be inaccurate in its health readings while also delivering a fairly poor user experience. This doesn’t feel good to the scientist in every general practice. Worse still, regulators are taking an interest: Inaccurate instruments affect patient safety.

Doctors themselves need training. Practitioners may not need additional advice on interpreting the results, but they will need new skills to work effectively in a wearable world. It’s not just a case of dealing with a swathe of new technologies; wearables will change the doctor-patient relationship. How, for example, will the breaking of bad news change when a patient already has ample evidence on their wrist?

Privacy. Privacy is a big concern for consumers, and companies like Apple have worked hard to respect the privacy of customers, particularly in a field as sensitive as healthcare. But we do need some benchmark rules for tracked data. At the very least, tracked data should not be shared with third parties, and patients should be reminded that they take full responsibility if they bring their data to an office and share it.

The more reasons there are to use data, the more people will buy in. Build it and they will come! The wearable health field needs to find new ways in which wearables can make a direct impact. For example, the largest group of people calling in to the NHS 111 helpline are mothers with young children looking for health advice or reassurance. Perhaps a big future wearable health application is the monitoring of children. Maybe we’ll soon be buying wristbands for whole families.

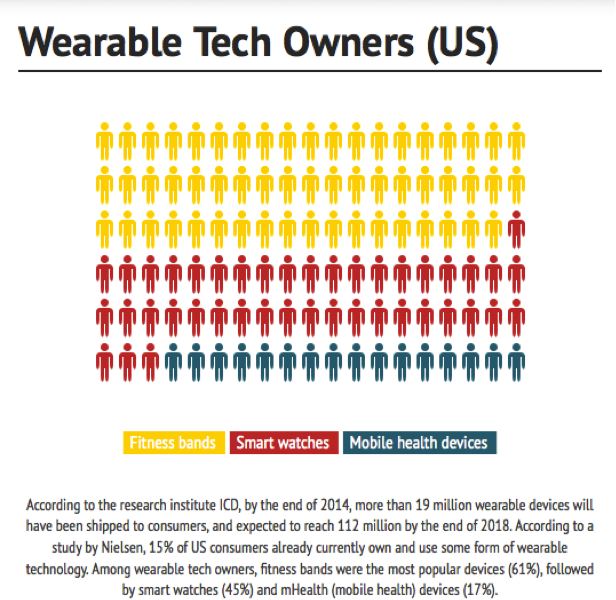

Data visualization provided by infogr.am

UK health technology startup Zesty has more than 1,500 healthcare professionals on their online health booking platform. It asked some of their private doctors how they would feel about patients turning up for an appointment with a suite of data in tow.

“We have spoken to many of our private general practitioners in London and the majority of them welcome the new opportunities offered by wearable health devices,” says Lloyd Price, founder of Zesty. “Some of our practitioners, like Dr. Gunasekera, are truly passionate about the opportunities presented by wearables and we want to help more practitioners to explore the potential. We also intend to approach companies like Apple and Samsung, so that patients can book healthcare appointments on their smart watches while presenting their tracked health data to health professionals at the same time.”

Apple just won a patent revealing that the company has actually been developing a smartwatch similar to the much-rumored and eagerly anticipated iWatch.

Dr. Bayju Thakar, founder of UK’s virtual health consultation startup, Doctor Care Anywhere, says that virtual GP consultations could benefit from additional tools such as wearable health devices. A doctor himself, he says that virtual GP consultations will soon reach a tipping point when late adopters understand and trust the service. With trust increasing towards wearable health technology from the doctor’s front, this point may come sooner than we think.

A recent UK report found that patient complaints to the General Medical Council had doubled in five years. Like all horrible headlines, this can be interpreted in many ways. In fact, part of the reason for the increase is that there are now more opportunities to feedback on GP services, including simple online methods.

Certainly, the doctor-patient relationship is in flux. Wearables will be another influence on that relationship, although even Dr. Gunasekera says that the technology has a long way to go. Wearable health won’t fix the NHS, but it can help remove uncertainties and keep patients motivated to participate in their own care. The sector just has to achieve the same degree of professionalism as the rest of clinical practice in order to gain true acceptance.