Between Mark Zuckerberg’s recent purchase of a home in the neighborhood and the regular anti-eviction and Google Bus protests that roll through Guerrero and 18th Street, the Mission District is the epicenter of San Francisco’s Gentrifi-pocalypse.

Just last week, a developer bought a shuttered auto repair shop in the neighborhood for a citywide record of about $350,000 in raw land costs per potential unit. So whatever these condos ultimately end up selling for once all the construction, permitting and marketing costs are filtered in will be much higher.

Yet the income disparities in the neighborhood are still stunning. I paid a visit last week to the Mission Economic Development Agency, a non-profit that has been serving the local Latino community for the last 40 years.

Nearly one-quarter of the students that they serve in the Mission’s four lowest-performing public schools do not have Internet at home.

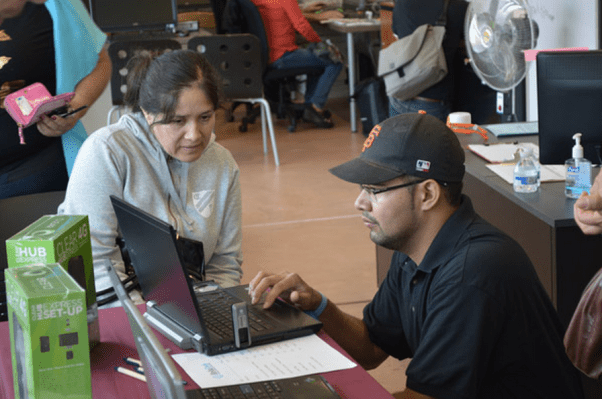

At MEDA’s Get Connected events, the Mission-based non-profit gets families signed up for Internet access and does giveaways or sales of refurbished laptops.

“It means that if they’re doing a research for a paper, they’re forgoing using the Internet or using a smartphone,” said Richard Abisla, who is MEDA’s technology manager.

Abisla’s work is part of a new federal effort that’s trying to replicate the ideas of the Harlem Children’s Zone and its creator Geoffrey Canada, who figured prominently in the documentary, “Waiting For Superman,” in other neighborhoods across the country.

Canada’s idea was to pair reform-minded charter schools with a wealth of non-profit services serving children all the way from birth to college. A study in 2009 from two economists at Harvard and Princeton found that the program astonishingly closed the black-white achievement gap for middle school students in math and cut it by half in English, although the Harlem Children’s Zone has since received criticism that it was so well-funded that its results can’t be duplicated for public schools nationwide.

Nonetheless, President Barack Obama has allocated at least $90 million in grants since 2010 to copy the model in other neighborhoods.

The Mission was chosen as one of them.

So Abisla’s spending his time trying to convince local Mission residents to buy things like routers and Internet service for as little as $10 a month.

“We hear them say a lot, ‘Oh, that’s not for me. I don’t speak English. I didn’t go to school,'” Abisla said. “Our approach has to be multi-pronged. We have to de-mystify technology for parents, especially newer immigrants who have never approached it before. We have to explain to them that it’s a necessity for their children to do well in school.”

MEDA also recently started a program called “Mission Techies,” that runs classes for neighborhood teenagers and youth on programming. They’ve been able to recruit Facebook and Google engineers to moonlight as volunteer teachers.

On Monday night, Facebook Messenger engineer Kurtis Nusbaum was teaching Android programming a group of 17 to 24-year-olds at MEDA with a friend RJ Marsan, who works at Google. They were running students through modules from Code.org, which is Hadi Partovi’s effort to make computer science education much more mainstream.

“There’s a feeling that tech workers aren’t involved with the community,” Nusbaum said. “I wanted to prove that wrong.”

MEDA has run one eight-week session of Mission Techies already.

Edwin Gonzales, a twenty-two-year-old who returned to San Francisco from El Salvador to live with his parents in Bayview, was able to get an internship at Jones IT doing diagnostics after being part of the last group. Even though he finished the program, he keeps coming to class.

Before, he was working at the Franciscan Crab Restaurant on the city’s touristy Fisherman’s Wharf.

“I’m very passionate about computers,” he said, explaining that when he was 14 years old, he helped his high school teacher in El Salvador build a computer. “I need to keep growing my skills.”

Why should you care? Well, a couple things:

1) Even though the U.S.’s inner cities are seeing less crime and more economic prosperity compared to 30 years ago and tech entrepreneurs are tackling urban problems like transportation and logistics, the dark flipside of this story is that American poverty is being suburbanized.

Today, only one-third of MEDA’s Latino clientele still lives in the Mission. About one-third of them come from other neighborhoods in San Francisco like Excelsior or Visitacion Valley, and the rest are commuting over from suburbs and exurbs in the East Bay like Richmond and beyond.

This is a local incarnation of a national phenomenon. You can see it in Los Angeles and Atlanta too, in these in-depth stories from The New York Times and Politico. Today, the U.S. has 3 million more people living in poverty in suburbs compared to big cities.

It’s a problem because the transit-rich density of U.S. cities actually makes them far more effective at delivering services to low-income populations. A generation ago, the national conversation was about inner city ghettos. But today, these communities are being gentrified out and suburbs do not have the infrastructure to deal with entrenched poverty. On top of that, the federal and city programs and non-profits that cater to these communities have literally taken decades to develop.

So there is a pretty deep irony that while tech startups are increasingly addressing urban inconveniences like food delivery and ground transportation, a poorer population is being physically marginalized from job opportunities and the largely city-based social services that were designed to lift them up over the last 40 years.

2) The tech industry has a problem with ethnic and gender diversity (and knows it):

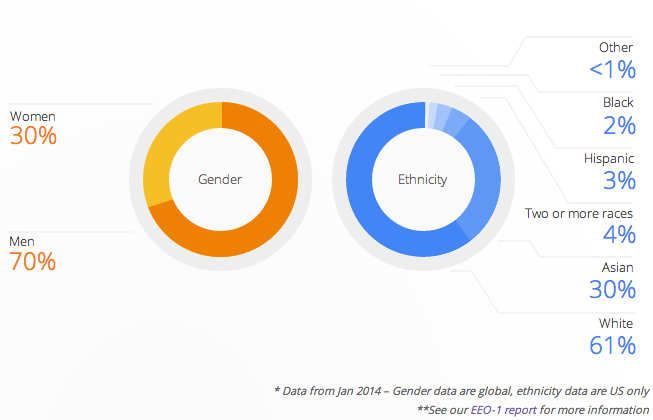

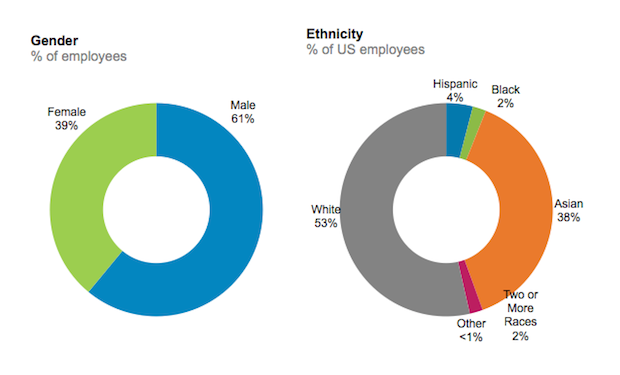

In recent weeks, both Google and LinkedIn have made the gutsy moves of sharing the numbers we all knew.

Here’s Google’s data:

And LinkedIn’s data:

It’s always characterized as a pipeline problem. Not enough minorities and women come out of four-year computer science degree programs, because not enough minorities either get the chance to go to college or get exposed to technology during childhood or in the K-12 system.

A vicious cycle continues because there aren’t enough minority role models in the system to shepherd others into the industry.

So why are we not building pipelines in our own backyards?

There are several existing programs that are running local classes in computer science for K-12 students like MissionBit, which uses volunteers from the industry in San Francisco’s public middle and high schools. Then there’s Hack The Hood, an Oakland-based non-profit that teaches technical skills to students and recently won a grant from Google.

There are also many jobs at growth-stage tech companies like QA testing that don’t necessarily require four-year computer science degrees and where a lot of the training happens on-the-job.

Surely, if Google and Facebook are the kinds of companies that envision being around for at least another 10 years, they could do more to support a diverse pipeline for that long-term future by being more systematically involved in local public schools. (Hell, I learned how to type as a five-year-old on Mac SEs donated by Apple.)

3) Lastly, for the political will to exist for increased growth (both of the housing stock and of the tech industry generally) in the Bay Area, tech companies have to show that the job and wealth creation benefits everyone locally.

This is hard to do given that we are at or near full capacity regionally in housing and transit, creating huge pressures for rent hikes and no-fault evictions. San Francisco’s population has never been higher and unemployment is near a record-low. BART is expected to be at full capacity by 2016 and the city has $6.3 billion in unfunded needs just to maintain its current transit system.

Activists complain about the Google buses and the city turning into a bedroom community for suburban tech campuses. But what they don’t realize is that we have several companies right now headquartered in San Francisco that will need to grow their headcount by a significant amount over the next five years.

Dropbox. Square. Salesforce. Twitter. Uber. Airbnb. Stripe. Not to mention all of Y Combinator’s other up-and-comers, many of which want to be headquartered in San Francisco.

Where are these tens of thousands of prospective employees going to live?

Mayor Ed Lee has a goal of building or preserving 30,000 units by 2020. But barring a macro-economic correction in the near future, this might actually be too conservative. San Francisco is already really behind, having added only 4,776 housing units from 2010 to 2013 while the city grew by 32,207 people.

As I’ve explained exhaustively before, the city’s politics around land-use and heights are complex. Then there’s a counter-intuitive set of political alliances that have emerged between wealthy, homeowning NIMBY-ists and affordable housing activists who add extra restrictions to the planning process that are well-intentioned but end up exacerbating the housing shortage.

On near record-low turnout a few weeks ago, voters passed Proposition B. It will require developments exceeding current height limits — usually around 40 feet — across much of the city’s waterfront to face a citywide vote. Proposition B’s passage means two individual developments, Forest City and a new San Francisco Giants project, containing around 2,500 housing units, will have to go and be placed on the ballot starting in November.

A few affordable housing activists were skeptical of extra waterfront construction, saying that it would be pretty much all be luxury condos.

The thing is, if new housing isn’t created regionally (including on the waterfront, down on the peninsula and the Western neighborhoods) on criticism that it’s just for the ultra-rich, existing homes elsewhere like in the Mission, Bernal Heights and maybe eventually Bayview end up becoming luxury-priced.

Furthermore, the city subsidizes the creation of below-market-rate housing with market-rate construction through a policy called inclusionary housing. The “right” ratio of market-rate to affordable units is a huge point of contention. But right now, without the federal or state support that the city has historically received, more market-rate construction is a key way the city uses to generate funds for preserving or building affordable units.

It’s all rather complex.

But if you want to change the existing political dialogue from something that pits tech against the city, mutual good will and understanding needs to be built now.

Education and the digital divide is a great place to start, and it’s right here on our doorsteps. It would kill many birds with one stone.