There is a constant tension about education in labor economics these days. On one hand, education is strongly correlated with income and employability. Workers with college degrees, or even just some university-level courses, are significantly more likely to have a job and to be paid better, as well. This is borne out by today’s U.S. jobs report, which showed a decrease of unemployment for college graduates, but an increase of unemployment for high school graduates.

The tension comes when you look at the government’s projections for job growth over the next decade. The jobs with the highest expected growth are also among the jobs that are least likely to provide a living wage, occupations like personal care aides (median salary: $19,910 per year), retail sales people ($21,110 per year), home health aides ($20,820 per year), food preparation workers ($18,260 per year), and the list goes on. In fact, of the top 20 occupations with greatest expected job growth, only two of the categories are above the current median wage of the country.

This is the largest problem facing society this century.

There has been much discussion over the past few weeks about Thomas Piketty and his book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Piketty focuses on the increasing divergence of the income and wealth distributions between the top percentile and everyone else. Left mostly unanalyzed in the book, however, is how people at the top of the labor market are able to leverage their abilities so much more than those in the middle or base of the market due to a combination of technology and finance.

We need to disabuse ourselves of the theory that just a little more education is going to change the fundamental dynamic of how the Internet economy functions. Instead, we need to understand how productivity is changing today, and why education is highly unlikely to smooth out those changes. Instead, we need to think bigger if we are going to create a more equitable and inclusive society.

Bullshit Jobs and the Power of Leverage

Productivity is among the most important measures of an economy. In economics, a production function takes a variety of inputs – typically, labor and capital – and outputs the quantity of products that are produced. As productivity increases, we have the ability to produce more goods while maintaining the same inputs, a wonderful outcome because it means we can serve more of our wants without additional costs.

Productivity has for the most part increased monotonically over the course of civilization (the European Dark Ages being a notable exception). We started off as hunter-gatherers and eventually developed rudimentary agricultural techniques that allowed us to stay in one place while meeting our food requirements.

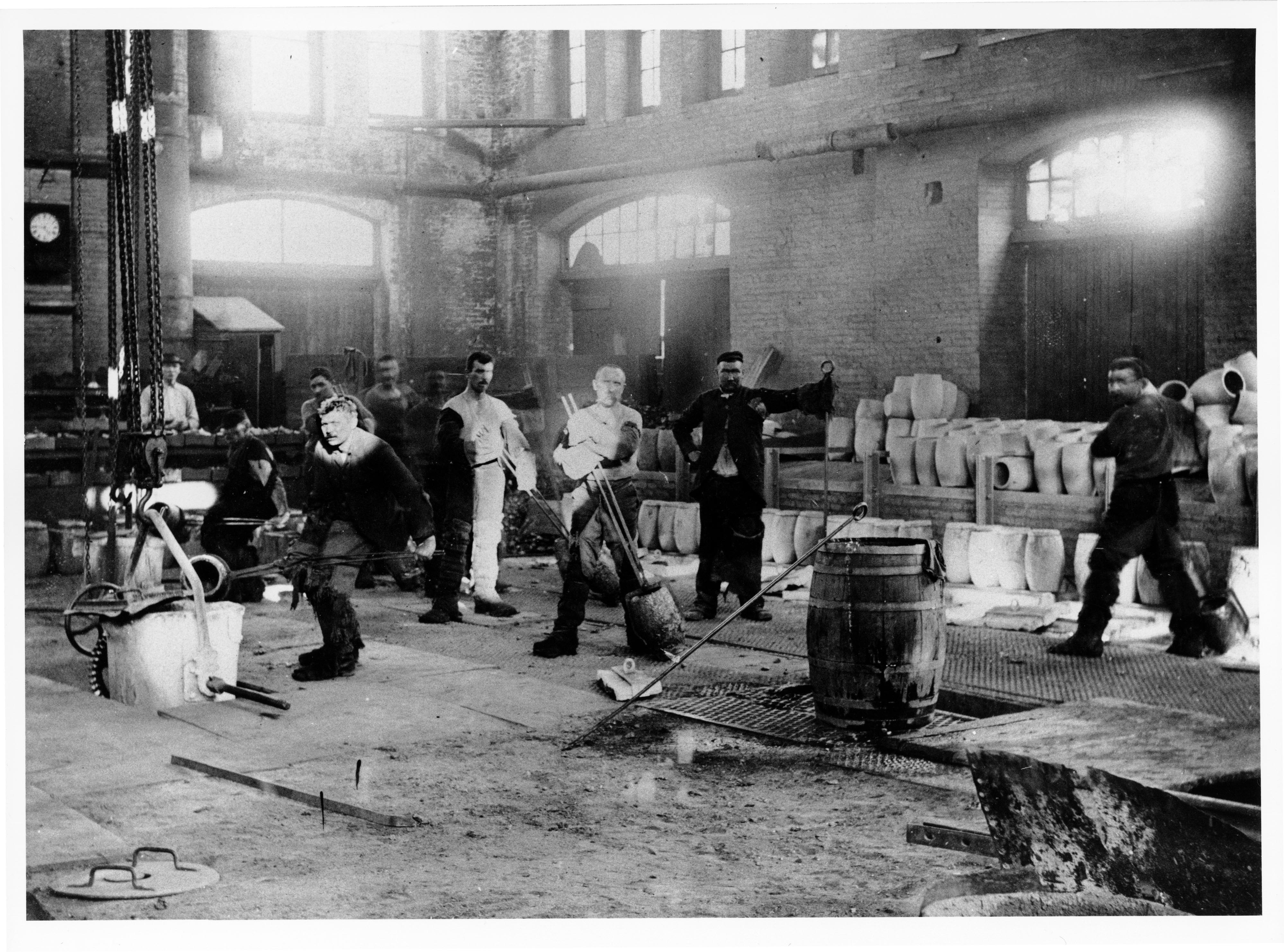

Civilization flourished as workers could pursue activities outside of food acquisition, and that economic specialization has continued throughout history. Today, only 1.5 percent of the American population is involved in agriculture, and only 8.2 percent or so is involved in manufacturing. That specialization has been particularly beneficial for the length of the work week, which has declined throughout most of history.

Photo credit: Kheel Center

Except, that is, until last century. Despite the impressive gains made in productivity, workers continue to spend thousands of hours a year toiling away, whether in services, information technology, or manufacturing. According to the OECD, workers in America averaged 1,790 hours of work per year, while workers in nations like Korea and Mexico work an average of over 2,000 hours per year.

This is profoundly surprising, because one of the most influential economists of all time, John Maynard Keynes, once predicted that we would have a 15-hour work week by 2030. Clearly something happened.

One recent influential viewpoint on this matter comes from David Graeber, a professor of anthropology currently at the London School of Economics. He posits that more and more of humanity is engaged in “bullshit jobs,” which he defines as jobs that exist in the “administrative sector” – the paper pushers that keep modern society moving along.

Graeber tries to analyze what’s going on. “It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working. And here, precisely, lies the mystery. In capitalism, this is precisely what is not supposed to happen.” Since it costs money to pay these paper pushers, shouldn’t we expect them to disappear through automation?

Replacing a paper pusher with an automated machine requires capital, and most human labor outside of a handful of rarefied industries is quite cheap.

His argument is fairly simple: we could almost certainly do without all of these jobs, but “the ruling class has figured out that a happy and productive population with free time on their hands is a mortal danger.” In a society in which so many desire to become the boss and have a small army of direct reports, his frank analysis is perhaps not too far off the mark.

The less conspiratorial answer, of course, is that replacing a paper pusher with an automated machine requires capital, and most human labor outside of a handful of rarefied industries is quite cheap. When you think of the fast food industry, for instance, nearly all the jobs in a typical restaurant could be automated, but we continue to use humans because hardware is pricey. This is why Bill Gates believes that we need to be careful about raising the minimum wage, since it is the cheapness of labor that keeps its demand high.

This is the fundamental difference between the two groups of workers we increasingly see in our economy. One group is paid for their time hour-by-hour, doing readily replaceable tasks that continue only so long as they keep their wage depressed. A much smaller group of workers, though, has the ability to leverage their talents to uncouple their hours worked from their wage. Software engineers are a prime example.

But the interesting challenge for productivity is that even those high-leverage jobs are increasingly becoming automated. Automation has been going on since the Industrial Age, but the Computer Age has really pushed that to an extreme. At first, it was just industries like accounting, where entire rooms of human calculators were replaced with spreadsheets. But today, it is lawyers that are getting the boot, and other professions like doctors seem likely to be challenged as well.

Read More. And More. And More.

There is a deep myth in Silicon Valley that education is the solution to this split in the labor force. If only people had more education, or that their education were more focused on marketable skills, then we wouldn’t have the employment problems we see today. Internet plus free courses with a smattering of TED Talks, and we should all be good to go.

There is some truth to this, of course. For many years, economists have argued that there is a race between technology and automation on one side, and the ability of our society to educate its citizens to take on more and more complex tasks. The argument goes that computers have simply evolved faster than our education system over the past few decades, and our race for education is falling behind.

That seems reasonable, yet it seems difficult to believe that we can truly increase our academic productivity in any sort of radical away for the individual learner to counteract that automation. While disparities remain huge in the American educational system, and the cost of education is flat-out ridiculous, our ability to move someone from elementary addition to advanced specialties has not been significantly cut over the past few decades. We can only input so much knowledge into the human brain at a time.

Two different types of startups are trying to change that, but both will meet resistance. One is the rise of MOOCs – these massively open online courses that were the height of hype last year, but that seem to have quieted down more recently.

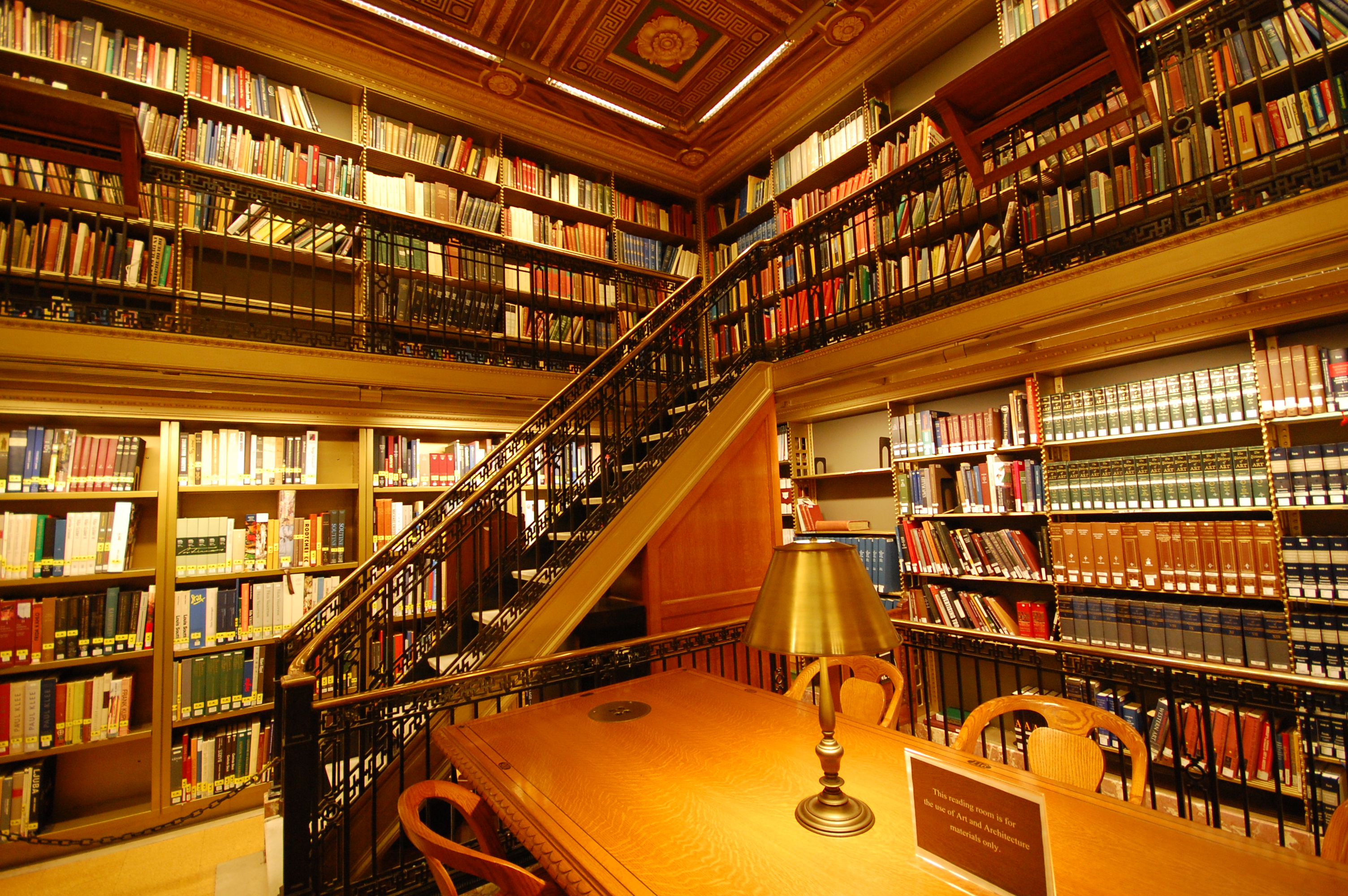

These startups aim to make learning free for everyone, everywhere. It is indeed crucially important to disseminate the widest amount of human knowledge possible. Unfortunately, free access to knowledge has never really been the problem in the education system. Libraries have held most knowledge on their shelves for centuries, and yet our society isn’t swimming in PhDs. The Internet has certainly made knowledge acquisition more convenient, but that doesn’t seem to be an underlying issue here.

Photo credit: Flickr user Gabriel Rodriguez

One of the key problems with education is that motivation itself is one of the largest determiners for success, and character is difficult to teach. But even students with motivation don’t always have the time to engage in the kind of intensive study needed to enter the professions with the most opportunity for leverage. Workers in many industries are forced to work two or even three shifts just to survive, leaving little time for education no matter how convenient. Thus, MOOCs often end up benefiting those already capable of learning – the very knowledge workers who didn’t need the help in the first place.

An interesting response to this comes from the rise of code schools or code boot camps, where people go to courses for a 12-week period (or whatever the case may be) and learn coding very rapidly. I have had a number of friends who have used such programs, and they seem to have enjoyed the experience pretty well.

Here’s the key question though: if people can take a 12-week course and get a job on the other side paying $90,000, aren’t we looking at a serious labor market imbalance that will correct itself when more entrants show up in the marketplace?

This is one of the problems with the idea that we should increase trade schools in the United States. In every labor market, the more workers that enter the market, the lower the prevailing wage in that market. If we really think that everyone would be rich if they become a software engineer, then we don’t understand the basics of market-based salaries.

There is an obvious solution here, one that is controversial in U.S. education circles. One option is to simply specialize children earlier in their academic training, such as in high school or maybe even middle school. It doesn’t seem to make sense that students are in school for 16 years only to learn what they want to do in their final years of college. This would have to be coupled with periods of retraining that would allow workers to move between similar specialties throughout their career.

But instead of confronting this reality, we continue to tack on requirements to grade-school students to try to prepare them for an array of specialties that they may never consider. I have this frustration even within the startup community, which has vocally called for high schools to be required to teach computer science.

There needs to be greater guidance for both students and adults about what skills are actively demanded in the marketplace, as well as how to acquire such skills.

There is always a call to add requirements, but where does the time come from? Should we be scaling back language classes, math classes, or something else? The level of base knowledge needed to be a “cultured” adult seems to only increase without end. As our knowledge of the world rapidly expands, we have to accept that most of us are going to be ignorant about a great many topics. We can’t simultaneously teach all of the engineering disciplines, social sciences, and humanities to every child if our hope is to get them prepared for a meaningful life.

Education shouldn’t just focus on children, though; it has to be part of a lifelong commitment to improving and adapting our minds to the needs of our society and our changing personal goals.

Today, a growing number of employers don’t want to train new workers, but instead desire workers who already have the skills they are looking for. Given the state of unemployment in the economy, there are many employers who can be quite choosy with whom they select, and thus the skill requirements for new employees have been increasing.

There are two directions to consider here. There needs to be greater guidance for both students and adults about what skills are actively demanded in the marketplace, as well as how to acquire such skills. Whether it is financial modeling, programming, or essay-editing skills, directing workers to the right resources with accurate counsel would be highly valuable.

The other direction is to consider how to guide employers to choices that actively encourage them to engage with workers and develop them. Employers need better options than expensive executive-education courses (an extremely profitable market these days) in order to get the right return on investment. Making it easy for employers to add the right training while keeping costs low could actively provide employees with the skills they need to continue productive lives.

Finding the Bigger Picture

Our economy is increasingly making some people richer and others poorer. The reason is an underlying mechanic around leverage. Most people work at jobs that are easily replaceable, while a narrow group has the ability to amass larger income by leveraging their time, often through technology and finance.

While education has often been the answer to this problem in the past and also is deeply embedded in the value system of Silicon Valley, it seems to be incapable today of giving humans the opportunity to compete with machines for work. Our technology has done something wonderful – increasing productivity while cutting labor costs, but at the expense of a far more inequitable economy.

Imagine if workers had the ability to take a year off from work at their old salary as long as they focused on building a skill set in a needed area of the economy.

As the pain increases, questions about distribution are only going to become more prominent, an issue that startups seem ill-equipped to handle. The people on platforms like YouTube and Kickstarter who leverage their networks can make hundreds of millions of dollars (see Maker Studios and some of the other multi-channel studios or Oculus Rift), but everyone else makes essentially nothing for their efforts. That is unlikely to remain tenable as our occupational futures become increasingly bifurcated.

The only answer to such systemic issues is through a wider lens on the problem. One solution is to move toward a model of specialists that regularly adapt to new work. Imagine if workers had the ability to take a year off from work at their old salary as long as they focused on building a skill set in a needed area of the economy. Programs like this already exist for laid off workers, but these programs could expand to encompass everyone.

Another option, popular with Thomas Piketty, is to devise a global wealth tax. The idea is simple – charge a really small percentage tax on wealth, creating a disaggregating effect on wealth in the economy. Beyond its impracticality in a globalized world though, it seems a tax is the wrong kind of model to solve issues around automation.

For us in the startup community, maybe there is a real opportunity to provide leadership here. We could create labor markets and structures that direct people to the most lucrative job offerings, and advise people in real-time of the classes, people, and projects they should be engaging in order to progress in their careers. I have brainstormed publicly that a real-time labor market protocol may solve some of these problems. At sufficient scale, this might just turn back the split in the labor force we have witnessed recently.

It is not often we get to work on some of the largest issues facing humanity. We need to take advantage of the moment, and work to solve the underlying labor problems that plague our economy. We created many of the dynamics we are seeing today – let’s do our part to reform it.