I write to you from my vacation, meaning, this time, the dusty port town of Kaolack in sunny Senegal. (What, your vacations don’t involve long hours spent riding in–or, sometimes, on–overcrowded West African inter-city public transit? Weirdo.)

The day I arrived I picked up an Orange SIM card, which cost me 1000 francs (US $2) and came with 1000 francs of credit, and then got my phone’s APN configured for some sweet 3G Internet. So far so standard, nowadays. But then my cab driver kind of blew my mind.

I apologize for getting all Thomas Friedman on you here. But still. I mean, I knew mobile money was big-verging-on-ubiquitous in East Africa, though M-Pesa–which, incidentally, has just expanded into Europe–but I hadn’t realized that it has grown so commonplace here in the West that it is used by cab drivers at gas stations. You can use “Orange Money” for both payments and transfers, here in Senegal, and even internationally to Mali and Burkina Faso.

In fact, across the developing world, where the vast majority of the population doesn’t have bank accounts per se, mobile-phone carriers have, or will, basically become their nations’ dominant banks. Oh, they’re not lending money–yet–but if you allow your customers to withdraw, deposit, pay, and transfer money, then you have basically become, for most intents and purposes, a retail bank. I don’t know how I didn’t notice until now that while software was eating the world it incidentally already pretty much ate most retail banking across a huge swathe of Earth.

Unfortunately, its next meal here may be slow to arrive.

The smartphone revolution is already en route, of course. On Tuesday I took a sept-place from Dakar to Saint-Louis; one driver and seven passengers crowded into an ancient Peugeot station wagon for five hours, upper-tier public transit but public transit nonetheless. The woman to my left kept tapping at her dual-SIM Samsung Galace SQ; the man in front of me had a T-Mobile branded Galaxy S, presumably secondhand from some European nation. (T-Mobile isn’t active here.)

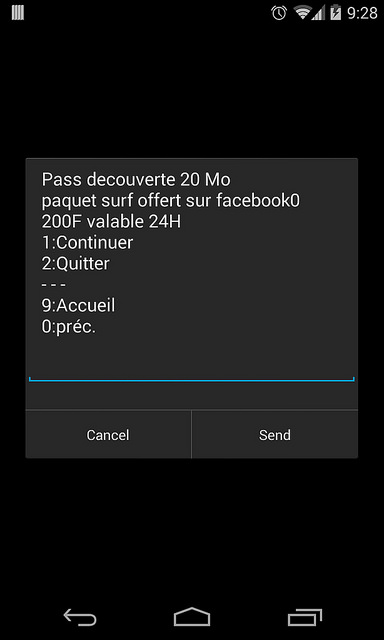

But new phones remain pricey — the cheapest Orange offered was the Galaxy Pocket, for US$120–and worst yet, data is crazy-expensive. I am currently paying Orange twice as much per megabyte than I pay T-Mobile back in the USA, where I’m not on an unlimited plan. (By contrast, in India three years ago, 1GB cost me $1.) Alicia Levine recently wrote a terrific piece on how Facebook and Google are fighting for the next five billion customers both with their phone/balloon Internet plans and their “Facebook Zero” and “Google Zero” zero-cost-to-access-our-site initiatives. Advantage Facebook, here and now, as per this screen shot from my Nexus 4:

but as much as I’m sure they’d love to have everyone on the planet walled within their garden, the Internet isn’t particularly useful if its free content consists entirely of Facebook — and/or Google, Wikipedia, Twitter — and everything else remains oppressively expensive. In the long run, now that the carriers here are also the banks, it’s probably to their own benefit to cut data access costs and reap the long-term economic rewards. Let’s hope they see that too.

Image credit: yours truly, Flickr.

Irrelevant footnote: I have now posted to TechCrunch from no fewer than a dozen different nations, mapped here via World66. (Canada, USA, the UK, France, Turkey, Senegal, Ethiopia, Kenya, India, Myanmar, Cambodia, the Philippines.) Do I win a prize? I bet John Biggs has me beat cold, though.