Monument Valley, the much-anticipated iPad and mobile game from London app & design studio ustwo (maker of the late lamented antisocial photo-sharing app Rando), will be launching globally on April 3 — priced at $3.99/£2.49, TechCrunch can confirm.

Although originally trailed as iPad-only — and then ‘iPad first’ — Monument Valley will actually be available for iPads, iPhones and the iPod Touch on its global launch date.

An Android version of the game is also in the works, due for release in a few weeks’ time, according to the company.

Ahead of Monument Valley’s launch, ustwo has released a short behind-the-scenes documentary (embedded below) which includes interviews with members of the game’s development team.

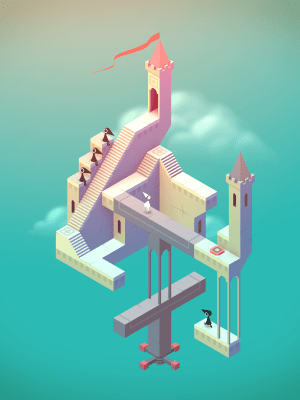

As I noted in post last November after playing with a beta version of Monument Valley, a core part of the game’s appeal is how its visuals dovetail with and inform the gameplay — making a unified experience that’s both fun to play and beautiful to look at.

It’s a big shift in style from ustwo’s most successful game to date, Whale Trail, which has clocked up a total of ~5.2 million downloads, since release back in October 2011.

With Monument Valley, there’s more tonal overlap with another ustwo mobile game — last year’s minimalist puzzler Blip Blup — but where the latter took a very skeletal approach to design, the former fills in the blanks with gorgeous aesthetics.

“Everything in the game both works in a mechanical sense but also looks visually amazing,” says Monument Valley’s senior designer, Ken Wong, in the documentary. “There was this idea at the start of the project that every screen of the game would be a work of art in itself… I think it’s a different way of approaching making a game, where the aesthetic experience is really driving the experience.

“Every screenshot could be printed out and hung on a wall.”

Monument Valley’s blend of architectural aesthetics and visual trickery is inspired by MC Escher’s surrealist designs. But various other influences evidently pervade the game (more on that in the Q&A below).

TechCrunch got hands on with the full version of Monument Valley ahead of the public release. The biggest change versus the earlier beta is the addition of audio — a huge previously missing piece of the puzzle as the sound design is very much a key part of the experience.

Audio instrumentation augments the player’s actions and can even feel like it’s helping to inform which actions to perform — with changes in pitch reflecting how you rotate and manipulate individual blocks. At other times, you can get caught up in just making impromptu melodies with your movements.

The game’s visuals are also now entirely polished, with sumptuous and (at times) animated scenery providing the backdrop for the game’s protagonist, Ida, and the other characters she meets. Smaller animated details have also been filled in to flesh out the characters, injecting shots of personality into proceedings despite dialogue and interactions remaining purposefully minimal.

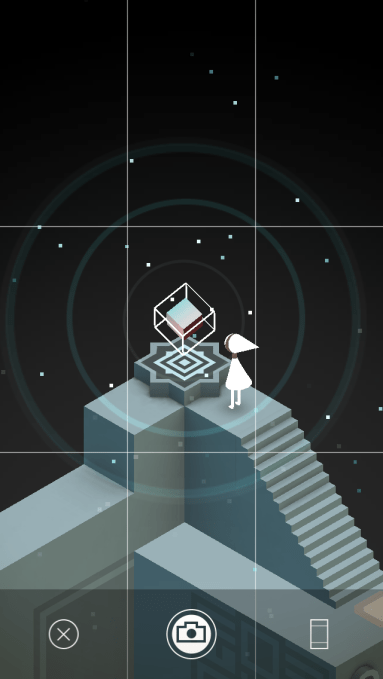

A new built-in camera function also allow players to compose, take and share screenshots of completed Monument Valley levels — another neat addition which plays to the social sharing circus and obviously makes more hay from the game’s visuals.

Ahead of Monument Valley’s global release next week, I asked Wong, to answer a few questions. Our Q&A follows below.

TC: How big is the MV team & who are they (names & roles pls)?

Ken Wong – Senior Designer

Peter Pashley – Technical Director

Neil McFarland – Director of Games

Manesh Mistry – Programmer

Van Le – Programmer

Michael Anderson – QA Manager

Dan Gray – Producer

David Fernández-Huerta – Animator

TC: How long was the entire development time for MV — from coming up with the original idea & doing the first bits of storyboarding, to coding, designing & testing it all out?

Monument Valley took about 10 months from start to finish. One thing I think we did right is not to have a fixed idea of what the finished game would be like. We allowed ourselves to experiment and explore, knowing that we’d discard the majority of our code and levels in the search for a very focused, elegant result. So maybe 7 of those months was exploration, and only the last 3 was really about finishing up the final content.

TC: The design is described as minimal — and that could also apply to the gameplay (e.g. you could have added a timer for completing levels faster, or scores based on number of steps to complete and so on). It’s deliberately pared back. What sort of atmosphere were you trying to create for the player?

Looking back, I don’t think we ever pared back the components of the game. From the very first prototype, the game was about getting a character to the exit of a surreal landscape, by manipulating architecture. The game never became much more complicated than that. Rather than see Monument Valley as minimalist, perhaps it’s more accurate to describe games that try to do everything as bloated.

What I wanted for the atmosphere of the game is to echo what M.C. Escher achieves in his art. He found a way to combine art and geometric concepts in a way that normal people could find beautiful and fascinating, while at the same time forcing them to think about the nature of representation and reality. By not burdening the player with time limits, complex character relationships or missions, we invite them to figure the world out for themselves. I think this results in the kind of joy of playful discovery that only interactive media can bring.

TC: How many levels are there in all? Will there be additional levels offered as downloadable content or is the game a complete & coherent entity as is?

From the very beginning, we wanted every level to have its own distinct gameplay or architectural ideas. One level introduces the idea of rotating architecture; in another level Ida needs to find ways to get past the enigmatic Crow People. From a list of two dozen concepts we prototyped and tested and eventually cut down to ten levels, which is the perfect length for us to tell our story.

We worked really hard to make Monument Valley a complete, satisfying experience. If players enjoy the experience and tell us they want to visit this world more, I’m sure we can explore more adventures with Ida.

TC: Who is Monument Valley for? What sort of player did you have in mind when you created it?

I think we first and foremost made a game that we ourselves would like to play. Most members of our team seem to have both left-brain (logic, reasoning) and right-brain (creative, emotional) interests, and I think Monument Valley is a result of that. Every level is an intertwining of puzzles and architecture, of code and graphics. We were surprised to discover that this resonated with a very wide audience. Friends and coworkers and strangers who had no interest at all in video games were very curious and eager to try what we were working on. So I think the secondary consideration for us has been to make a game that non-gamers might be interested in.

Our job as artists and creators is to show people something beautiful or surprising – to invite them to surprise themselves, to explore and interact. We had to find ways to challenge our audience without overwhelming them, to describe complex ideas in simple, elegant ways.

TC: Which levels were the most complex to design & build? Which are the teams’ favourites?

Every level had its own set of unique challenges. The Descent is driven much more by atmosphere than puzzles compared to other levels. The two levels featuring Crows were very difficult because we had characters walking and interacting on impossible geometric structures. I had a lot of trouble settling on the visual theme of the final level in the game. The Box is a very difficult level to work on because of all the non-Euclidean geometry going on.

I just asked the team members currently in the studio and they each had a different favourite level in the game.

TC: What specific sort of expertise/experience were you looking for when you hired in to build out the MV team?

Most of the guys had already worked together on ustwo’s previous game projects, including Whale Trail and Blip Blup. Around a year ago the team hired in Dan and I, and David joined a few months after that. During Monument Valley we found that it was invaluable that each member of the team had multiple disciplines. David was hired for his animation and 3d skills, but he also produced storyboards and worked on the art of several levels. Manesh’s experience with music technology enabled him to contribute to the game’s audio. I’m an artist who can do a bit of code while Peter ‘Pash’ Pashley is a programmer who can do a bit of art, and together we did the bulk of the level design.

TC: I notice there’s a built-in camera function in the app to let people compose and take screenshots — how did you come up with that idea?

One of the design goals of the game was to make every screen a piece of art you could hang on a wall. Late in the production, when we had all these amazing looking scenes in front of us, Pash came up with the idea to enable players to share these from within the game. Van had it working a day or two later.

TC: Does the game’s narrative have a conscious message/moral?

TC: Does the game’s narrative have a conscious message/moral?

Personally, I’m not interested in shaping my work around a message or moral. Maybe I don’t know enough about life to be confident in a message I want to say to everyone. But I also feel that having a discussion is more important than having a conclusion. The ending of Monument Valley is important and shapes the rest of the game, but the real substance is in experience itself – going on a journey with Ida, discovering who she is and helping her get to the top of each monument.

TC: What design influences did the team have (Escher aside) — visual, auditory and thematic? Any other games that also inspired?

Something that people responded to from the very first bit of concept art is what I call ‘little worlds’ – a scene or building that was entirely enclosed within a single page or screen. People seem to find something very reassuring about seeing everything at once from this bird’s-eye view. The level becomes like a sculpture or a piece of graphic design. So a lot of the visual inspiration were in the form of enclosed shapes and forms – Japanese flower arrangements, cross-section diagrams, architectural models, typography posters and spot illustrations.

There was a very long path to get to the final audio in the game, during which we listened to a lot of music that mixed lo-fi electronica with traditional instruments. In the end the most useful reference was the ambient work of Brian Eno.

The three biggest game references were Windosill, Sword & Sworcery and Portal. Each of these is a short but brilliantly put together experience, pairing puzzles with intricately designed worlds.

TC: How did you go about designing the difficulty level of the puzzles? Is this designed to increase as players progress?

We want as many people as possible to be able to finish Monument Valley. If they are playing for the story or characters, it’s a shame if they can’t complete the game because their spatial or problem solving skills aren’t as high as experienced gamers. So we spent a lot of time user testing with non-gamers and casual gamers to balance the level of challenge. I’m not sure if difficulty is really the right term to describe the arc of the game… there are a few trickier puzzles towards the end of the game, but the solution is never too complex.

TC: Originally, MV was slated as an iPad game. But the release is for iPhone too — was this a conscious decision to open it up wider than originally planned from the beginning? What was the thinking here?

The line we’ve used in our trailer and on the website is “for iPad and other mobile devices”. The game looks utterly amazing on an iPad screen, but we’ve always wanted to make the game available for users of iPhones and iPod touches, so we spent a lot of effort getting the controls just right for the smaller screen. We’ll leave it up to the fans to figure out what “other mobile devices” might mean.

TC: Is it generally getting more expensive to develop quality gaming titles for mobile? (With so much competition vying for people’s free time)

I guess that depends what you mean by quality. During what I call the ‘dark ages’ of game development, the focus was on realism and graphic fidelity, both of which cost huge amounts of money. I’m really excited that audiences are increasingly appreciative of games that focus on aesthetics and creative gameplay – something that a student with a $1,000 computer and free online tutorials can accomplish. To be honest, I think general statements about the games industry are one of the things that is holding the industry back. We’re too diverse for that now. You can make amazing things on any budget.

TC: What were the biggest challenges in delivering on the original vision for MV?

When you create a game in an established genre, in a familiar art style, there are lots of tropes and conventions you can rely on. In trying to create a new sort of experience we had to develop our aesthetic and interactive language from scratch. Reliably rotating isometric objects with touch controls was hard. Getting ambient occlusion shadows to work on impossible geometry was hard. Creating levels that didn’t confuse or exhaust non-gamers, while keeping experienced gamers interested was hard. Making each screen in the game work as architecture, graphic design and as a puzzle was hard.

TC: What targets does ustwo have for MV sales, in terms of the level required to break even — and the level required to come away with a sense that the game has been a success for ustwo?

I don’t think any of us has actually sat down and worked out the numbers. Internally within the team, the game has already felt like a success for the past few months. We had a blast making it, and we all feel proud to have worked on something so personal and unique. The response to early builds of the game has been overwhelmingly positive, from friends and strangers alike, so we’ve never really worried about whether the press and public will appreciate the game.