You hear about graduate students who drop out to found startups, but I guess that would be too easy for Jeff Smith. He co-founded and serves as CEO at Smule, the startup behind social music apps like Ocarina and Magic Piano. At the same time, he recently received a Ph.D. in computer-based music theory and acoustics from Stanford.

Smith and I spoke earlier this week about being a full-time graduate student and a startup executive (not to mention the father of three children) since 2008. One of the questions that we kept dancing around during our conversation was: Why the heck did he feel the need to do this?

Apparently that’s a question that came up at Stanford, too. Smith recalled that during his Ph.D. qualifying exam, a committee member asked him, “Why are you here?” Smith had to admit that he wasn’t interested in teaching or becoming an academic researcher. So why?

“I’m really interested in music,” Smith said. “I want to study music. I want a formal program.”

You might think that Smule’s investors weren’t thrilled about Smith’s academic commitments either, especially since his co-founder Ge Wang is also an assistant professor at Stanford. However, Smith said it was never a serious point of contention — though investors would bring up the issue in an “indirect” way, by asking, “How do you feel about things? Are you committed?”

Board member David Cowan of Bessemer Venture Partners (his other investments include LifeLock, LinkedIn, and Reputation.com) told me that that Smith’s dual careers never gave him pause.

“I’ve backed founders who are bipolar and pregnant and had all kinds of distractions and impairments,” he said. “In general, if I can find an entrepreneur who is brilliant and passionate and honest, we’ll work around the other stuff.”

Cowan added that Smith’s background running a number of other startups (including Tumbleweed Communications, which went public) helped bolster investor confidence — not to mention the fact that Smule is having what Smith called a “transformational year,” setting a sales record of $2.4 million last month.

“That’s one of ways to tapdance around it,” Smith said. “It’s one conversation if things are going poorly, and another conversation if it’s up and to the right.”

Plus, Smith’s Ph.D. research was closely tied to his work at Smule — as he explained it, he looked at large sets of data, including user data from Smule, to understand how cultural differences lead to different styles of musical performances. (His dissertation was titled “Correlation analyses of encoded music performance” and you can read the abstract here and the full thing here.) Smith compared his work to composer Béla Bartók, who did important research into European folk music.

“I wanted to pick up where Bartók left off and see if we could begin to understand culture through a very different lens …. through the lens of art,” he said. “At least as far as the data goes, the answer is yeah, we can.”

For example, Smith said that his dissertation allowed him to analyze the extent to which different types of Western music have permeated China, as you can see in the embedded document below.

At the same time, I wondered if the research might also undercut the big vision for Smule that Smith and Wang have both laid out for me at different times — that music can be a form of communication that transcends language and culture.

“It’s quite complicated,” Smith said. “There is this universal expression of music that we’re seeing across the globe, but there’s a lot more nuance, there’s a lot more diversity of interpretation. It’s

a little less transcendent than I might hope it might be, but there’s still these common things that are binding people together.”

Discovering some of those common things actually allowed Smule to improve its products, he added. One of his findings: When people don’t know a song very well, they tend to play more quickly at the phrase boundaries, something that’s exacerbated in Smule’s Magic Piano app because the app tries to follow the pace of the player. By slowing the app down at those boundaries, Smith said the company saw a significant improvement in how many users would actually complete a song.

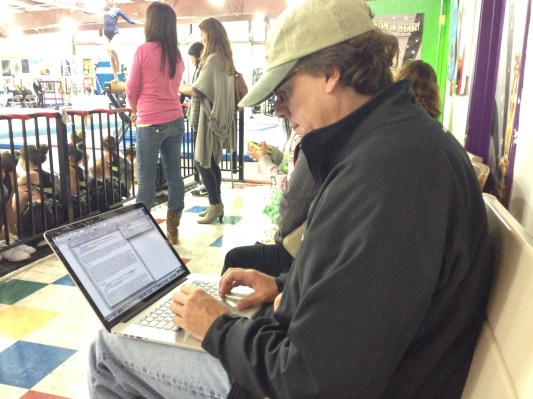

And yes, Smith said the time commitment of both roles could be a challenge. Apparently, any free time went to completing his dissertation, and he recalled sitting in the stands of his daughters’ athletic events and typing away (as you can see in the photo at the top of this post). His laptop, he said, was “attached to me wherever I went for a few years” — he was on his computer so often that he started learning special back exercises to deal with the strain. He also took vacations with the goal of getting more work done.

So how did it all turn out? Well, he got his Ph.D., and his professor Jonathan Berger told me in an email that there was “no negative impact on quality of work on either side.”

“Despite my initial trepidation — Smule fueled Jeff’s intellectual pursuits, just as his creativity

as a scholar and composer helped make Smule what it is,” Berger said.

Still, Smith admitted that his choice had its costs.

“At some level this whole thing is irrational, and I concede that it’s not something anyone should do,” he said. “It took a toll. I’m pretty tired.”

And now that he might actually have some free time, Smith told me, “I honestly don’t know what I’m going to do with myself.”