We’re all publishers now, and thanks to social media and digital broadcast networks like Twitter our idle musings can reach massive global audiences, hitting far more eyeballs than the graffiti scrawled on the proverbial toilet door ever could.

But the immediacy of social media apparently makes it easy for some users to forget how far their views can travel — causing a small number of them to end up in legal hot water over the things they have posted online. Or, from the establishment perspective, to threaten the judicial process by potentially prejudicing prosecutions.

The U.K. government’s chief legal advisor, Attorney General Dominic Grieve, whose remit includes trying to ensure fair trials can take place, has decided the time has come to provide free legal advice (well, he calls it “advisories“) to Twitterers and Facebookers to help educate them on the responsibilities of using a “tool of mass communication”.

From today, Grieve will be publishing court advisory notes that have previously only been available to mainstream media outlets. The notes will be published on the gov.uk website and via the Twitter feed of the Attorney General’s Office, @AGO_UK (which currently has less than 4,000 Twitter followers).

“I hope we will be able to keep it in simple language and terms,” said Grieve discussing the public advisories in a video interview with The Independent newspaper. “We may well give a slightly difference notice on the Twitter feed to the one we give to the print media, for example, where we sometimes say some matters in confidence. This will be a public document but I think it will have, I hope, an educational value.”

“People will be aware that this is an issue. And can also come to it as a reference point if they start thinking there’s a great deal of comment floating around about a particular case,” he added. “We have now an extraordinary tool of mass communication and it’s a wonderful thing. But I think that children particularly… need to be alerted at school that they have responsibilities.”

As well as trying to ensure social media users don’t trample over the ability of courts to conduct fair trials, Grieve noted the guidelines will aim to help people avoid saying things that might in themselves be a criminal offence.

Just last week, for instance, a man who flouted court directions by posting pictures purporting to be of Jon Venables, who murdered the toddler James Bulger in 1993 when he himself was also a child, was handed a 14-month suspended prison sentence.

Another recent example is Peaches Geldof, daughter of the singer Bob Geldof, who the Independent notes apologised this week for tweeting the names of two mothers whose babies were abused by the Welsh rock singer Ian Watkins.

There is also of course a libel risk attached to using social media to publicly discuss others — back in October Sally Bercow, wife of the House of Commons speaker agreed to pay £15,000 in damages to Lord McAlpine over a libellous tweet, in one example.

“I think there needs to be some education on this, because what you say to a group of two other people and what you say to thousands of people will be judged differently,” Grieve added.

Despite what is a historic move in the U.K. — to expand contempt of court advisories to any and all social media users — Grieve went on to stress that the problem posed to the criminal justice system by Twitterers et al is not a huge one.

“I don’t want to exaggerate the problem. The vast majority of criminal cases in this country — there’s some 18,000 Crown Court trials — take place without any difficulties whatsoever. It’s a very small minority which cause difficulties. Usually, those which are attracting a great deal of public attention — and those are the ones I want to try and tackle. Because if I can reduce it… most people in our experience who have tweeted wrongly, come back and say ‘I had no idea I’d done anything wrong’.

“So I think we just need to alert them, first of all, and try to make them understand why the issue matters.”

Getting the people who ‘tweet first, think later’ to have the prescience of mind to check the Attorney General’s Twitter feed and parse its contempt of court advice before letting off steam about so-and-so’s court case may prove rather challenging. But putting more information into the public domain on how to avoid crossing the legal line will, over time, allow it to be disseminated by the very networks that can cause bother in the first place — giving at least the chance for it to filter into more social media users’ bubbles.

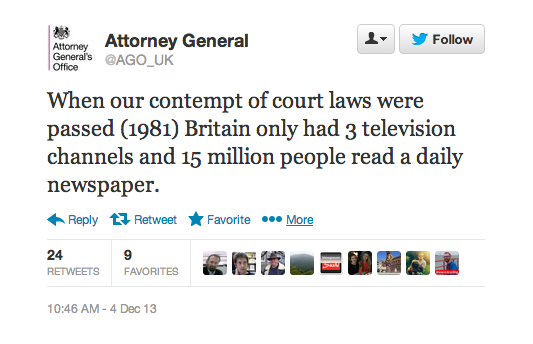

The Attorney General’s move is aimed at updating laws that have lagged well behind mass uptake of social media. But there is also a suggestion in its own data that information being shared via social media is influencing mainstream media to publish more than it might otherwise. The Attorney General said he has issued 10 media advisories so far this year — the most ever issued by the AGO, which issues five on average annually.