Marblar is a product development platform that lets users generate ideas for commercial uses of scientific discoveries that lay dormant in universities and research labs around the globe. Today the company is upping the stakes.

In a development that sees it get access to half a billion dollars’ worth of patents from NASA, ETRI, and the University of Pennsylvania, the London-based startup has also signed Samsung as a commercial partner to offer users the chance to help create the company’s next product and earn a share of revenue along the way. The move represents a rejigging of Marblar’s collaborative model that appears to address most, if not all, of the platform’s shortcomings.

Working with university Tech Transfer offices and various government research institutes, Marblar originally set out to tackle the problem in which authors of scientific discoveries very often don’t know what practical uses, if any, their breakthroughs might have. As a result, research labs have a pretty poor track record of commercialising their research.

However, Marblar’s platform aims to make “lightning strike more often”. It plans to do so through expert curation, crowdsourcing and gamification in a way that encourages lateral thinking, greater creativity, and collaboration among people from different disciplines.

Simply handing ideas back to universities or government research institutes hasn’t proven to be a good approach.

Lightning But No Thunder

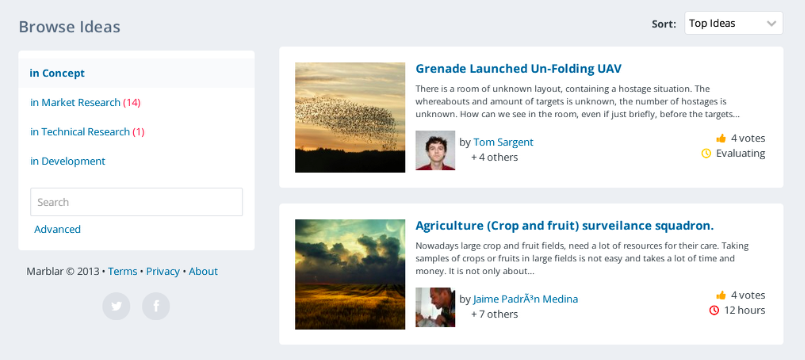

Launched almost a year ago to this day, 30 patents have been curated on the site, resulting in thousands of product ideas. This is proof, says Marblar CEO and co-founder Daniel Perez, that “people do want to think creatively around IP” and are capable of uncovering new applications for emerging and dormant discoveries. And yet something wasn’t quite working. Namely, very few of those ideas are on the path to commercialisation, instead being passed back to the same institutions where the original IP was gathering dust in the first place.

The way the startup was curating content didn’t scale, either, requiring universities to pay a listing fee per patent, thereby creating a disincentive for them to release swathes of IP. Meanwhile, along with desperately wanting to see their winning idea commercialised, users would sometimes raise the thorny issue of royalties, should the product become a commercial success.

Then the realisation: If Marblar were ever going to really fulfil its mission, it needed to not only persuade IP holders to post their discoveries on the site, but also to find commercial partners with a proven track record of bringing new technologies and products to market who would buy into its collaborative model to help find the next breakthrough product.

“Simply handing ideas back to universities or government research institutes hasn’t proven to be a good approach,” says Perez. “We were getting quite frustrated that we could hand a university several dozen new product ideas for their technology, but those ideas, even the really promising ones, weren’t going anywhere. In fact, a lot of universities didn’t even have the bandwidth or resources to read the ideas for their own technology.”

He says the company also learned that the way universities market their IP internally is also broken, consisting largely of posting patents to listing sites such as iBridgenetwork, or via email blasts. But similar to the problem that Marblar faced, a disconnect exists between IP holders and commercial companies in need of new technology.

“Every single corporate entity we’ve spoken to has mentioned they simply don’t bother with those emails or rarely browse a university’s IP list. If they have a product need they’ll google, see who has it, then approach that university if they think the IP would solve it”.

But more alarming, says Perez, and something that I sense has made him and his team even more determined to succeed, is that in many instances the path of least resistance for universities monetizing their IP is to sell to patent trolls. The irony, of course, is that many universities are funded by the taxpayer to help foster innovation, not stifle it.

But more alarming, says Perez, and something that I sense has made him and his team even more determined to succeed, is that in many instances the path of least resistance for universities monetizing their IP is to sell to patent trolls. The irony, of course, is that many universities are funded by the taxpayer to help foster innovation, not stifle it.

“I’d like to think that Marblar is the anti-troll,” he adds. “There is no reason for universities and government research labs to be sitting on piles of unused innovation or, worse, selling that innovation to trolls”.

A lot of entrepreneurs think hustling is just about emailing a bunch of people you don’t know.

A Meeting With Samsung

Faced with knowledge that Marblar’s existing model was never going to reach the moon, Perez did what many a CEO does when their back is up against the wall. He took to LinkedIn with a hit list of people at companies that he thought could help fix the startup’s problems and with whom he hoped to secure a meeting.

“We were really tactical in our approach, and on who we reached out to,” he says. “A lot of entrepreneurs think hustling is just about emailing a bunch of people you don’t know. We investigated deeply each person we approached. Our stalking would have made Edward Snowden boil.”

One of those was Luke Mansfield, Head of Product Innovation at Samsung Electronics, who, says Perez, in contrast to some of the other major corporates he approached, was immediately taken to the idea of working with Marblar.

One of those was Luke Mansfield, Head of Product Innovation at Samsung Electronics, who, says Perez, in contrast to some of the other major corporates he approached, was immediately taken to the idea of working with Marblar.

“We didn’t want to just pitch to Samsung, we wanted to pitch to the right person at Samsung. Luke Mansfield isn’t just a product innovation expert, he’s an Oxford-trained chemist. We thought if anyone at Samsung would get what we’re doing it’d be him. And we were right. He understood the potential immediately. And off we were.”

But at the same time, Perez had discovered that Marblar would need to dramatically increase the number of patents on its platform in order to get a company like Samsung to sign on the dotted line. Likewise, without a heavyweight commercial partner, persuading research institutes to release more of their IP created a chicken-and-egg situation. And although he won’t say who blinked first, or how imaginative Marblar had to be in its outreach and during negotiations, the results speak for themselves.

Not only is Samsung onboard, committed in principle to commercialising the best ideas generated by the Marblar community, but the platform will soon curate around $500 million worth of IP from new partners NASA, South Korea’s Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI), and the University of Pennsylvania, in part made possible by dropping the listing fees it previously charged IP holders. New patents posted range from those in aerial robotics, micro-sensors and new types of materials.

The new, much more ambitious Marblar would require a different business model.

A Hits-Driven Business

With two parts of a three-part puzzle now in place, Perez knew there was one more thing that needed to be addressed. The new, much more ambitious Marblar would require a different business model that would allow it to ditch the listing fees for IP holders and ensure that users and the startup itself could get paid in the long term.

Instead of prize money, Marblar’s users now earn a royalty if their idea or contribution leads to a new product being brought to market by Samsung, or one of the platform’s future commercial partners; 10 percent divvied up based on the number of ‘marbles’ users earn throughout the idea-generating process.

“We got a lot of feedback from our users, mentioning what they’d love is not just prize money but seeing ideas be realised, having lots more tech to chew on, and, importantly, sharing in the value created,” says Perez.

It’s also how Marblar hopes to generate revenue, with the company receiving a 5 percent royalty paid by the relevant commercial partner, not the original IP holder. In this way, explains Perez, there’s no risk for universities and government research institutes to post patents on Marblar, since it doesn’t cost them anything and, by their very nature, patents are made public anyway.

However, what’s most interesting about the company’s new business model is that rather than generating revenue every time a patent is curated on its platform, regardless of whether or not it is ever commercialised, Marblar is now entirely hits-driven.

If its users, working with IP holders and the site’s commercial partners, don’t produce a single product that makes it to market and sells, the company will eventually run out of runway. Conversely, should Marblar score a hit, on the scale of, say, the next ‘Post-it note’ or something as disruptive as the printed press, it could generate reoccurring revenue for a very long time. In that sense, lightning only needs to strike once for this UK startup to be a success.