I’m probably going to be consigned to whatever level of hell is reserved for pretentious editorialists for saying this, but sometimes when I’m trying to evaluate some new piece of technology, I consider whether Henry David Thoreau would have taken it to Walden Pond with him.

Wait, just give me a second. I know how it sounds. Let me explain.

I’m not some Neo-primitivist who thinks we should all go barefoot and use calorie-impoverished diets to extend our miserable lives. On the other hand, I’m suspicious of things people invent that have no purpose except a slight increase in convenience.

Yes, time is the only thing that we, as privileged first-worlders, can’t purchase. Convenience is the nearest thing to buying time, however, and it commands an understandable premium. That said, I can’t help but feel that our connected world (inclusive of the web and the devices we use to interact with it) is being populated with tools that would not look out of place in Skymall.

Google Glass is one of them (and I expect to see a knockoff in my complimentary seat-back magazine soon), but the objections against it are so obvious that I abandoned several articles enumerating them as unnecessary (one working title: HUD Sucker); at any rate, they have been expressed perfectly well by others, and I don’t plan on duplicating their efforts. Now that you know this isn’t about yet another opinion on the thing, you can move your cursor away from the “close tab” x, unless you’re reading this on Google Glass, in which case I beg to inform you, sir or madam, that it is not becoming.

But to proceed: Technology is about empowerment, and in fact I think that Thoreau’s modern analogue would find many useful tools to bring with him on his sojourn in nature.

The man was, after all, hardly a masochist or even what we would now call a Luddite, not that he had many technologies to which he could object in those days (“glow-shoes, and umbrellas”). He brought a grinder with him in the days when mortar and pestle were still in vogue, and of course many books, which were one of the primary means of entertainment, along with drinking and conquest.

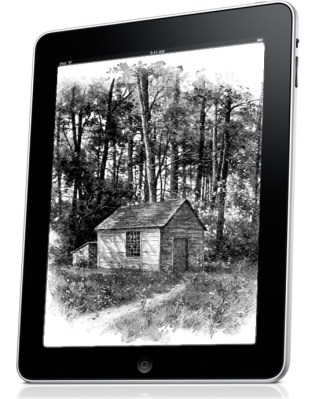

Picture this modern Thoreau embarking on his hermitage. He is not trying to return to the necessities of cavemen — he wants to carve and fill a niche that is big enough to hold him, his needs, and his edifying pleasures — but no more.

So while it seems unlikely he would find room in his bag for a Slap Chop or personal air conditioner, there are many marvels of modern technology which he would be happy to utilize. If he could bring the entire Western canon on an iPad (or e-reader, to conserve power), surely that would be preferable to choosing a bare two dozen paper books. A compass would be essential, but surely a GPS unit would not be amiss? If a knife, why not a multitool? And if I’m honest, if paper and envelopes, why not Twitter? But there things begin to unravel.

Enablers and facilitators

Anyway, the point is not to make an inventory of Thoreau 2.0’s bag (heavy waxed canvas, I think), but to express that the criteria he might use to select what goes into that bag are useful ones. The idea is to find things that extend our own natural powers, or grant us new ones.

There is a real difference between the tools, digital or physical, which empower us with new actions, and the tools which merely make existing actions easier. If you want to chop down a tree, it is not realistic to do it with your teeth. Yet once a man has an axe, it is only a continuum of difficulty between felling the tree with that, and felling it with a chainsaw. The difference between the two is only effort.

Similarly, if you want to communicate with someone across the world, or retrieve information hosted on a server thousands of miles away, you will need a tool — even the most stentorian or far-sighted among us could not hope to work in place of the most fundamental element of a phone or the Internet. But once that connection is made, as you add speed and modes of consumption, past a certain point you are no longer enabling new actions, but rather facilitating existing ones.

I’ve always liked Samuel Warren’s description of difficulty in Ten Thousand A-Year: “What is difficulty? Only a word indicating the degree of strength requisite for accomplishing particular objects; a mere notice of the necessity for exertion; a bugbear to children and fools; only a mere stimulus to men.”

Do we all need the digital equivalent of chainsaws, reducing the necessity of exertion to its absolute minimum? Note, I don’t think we’re quite there yet – our devices and networks are still developing. But once you see that something is not actually new, but only does what another thing did before faster or cheaper, isn’t it a rational choice to draw a line there — whichever side of that line you choose to stand on?

For more powerful tools carry risks and problems of their own, and some find that the cure is worse than the disease. It’s a mistake to write off such people as simply old-fashioned, or ignorant, or afraid of the future. There are sophisticated objections to these things on the tumultuous outmost margin of technology, every spasm of which is breathlessly extrapolated into some magical future by pundits with brief memories and narrow considerations.

Sometimes, on reflection, I find myself among their company. That’s why I like this little Thoreau exercise. A simple question: Does this add something new, as an axe or a mobile phone does? Or does it make something easier, as a chainsaw or Google Glass? And in either case, at what cost?

The answer is rarely surprising, but the process helps clarify what exactly it is that I think I need from these things, what they really provide, and what may come in the future to replace them.