Editor’s note: Maria Rocio Paniagua currently works at Flit, a PR firm that helps products, projects and events launch in Mexico. Follow her on Twitter @lachinous.

“When the geeks go marching in, good stuff can happen, but if everyone joins in, real change can take place.” That’s what the hackers and team behind Codeando México, a civil innovation platform where government and organizations publish projects, thought when they launched the #app115 challenge, an app competition that aimed to prove that great code can be very inexpensive if motivated by the right reasons.

What motivated them? A couple of weeks ago, the Mexican House of Representatives announced that they were planning to pay $9.3 million to have an app developed. The app would work on mobile devices and would monitor what went on in the sessions: bills, context, statements and media analysis. According to one of Mexico’s most widely read newspapers, they had hired a company called Pulso Legislativo (a company that allegedly has questionable relations with current and former legislators from the party in power) and had agreed to 32 monthly payments of about $290,000.

The cost caused outrage, because it appeared to be another case of fund misuse by the government. The team from Codeando México wrote a blog post breaking down the figure: “It is more money than what the three most active VCs funds invested in Mexican startups in 2011 and 2012. It is buying a taco for 11,500,000 mexicans, it is paying the annual scholarship support for 306,667 students or broadband access for a year for 17,500 families. It is what a team of developers would charge you to develop Angry Birds 77 times…you get the point by now.”

According to Oscar Mendoza, the analysis director of Pulso Legislativo, the company didn’t develop a native app; instead they were offering a private service through a web app that provided reports from and analysis of Congressional sessions — information that the legislators already had. Mendoza said they had distributed 550 access keys; however, a head count quickly showed that many legislators had no knowledge of the contract or app.

“Together we can go beyond angry tweeting, towards fixing the world on a Saturday night over some tequilas.”

A journalist named Arturo Aguilar launched a petition on Change.org, which almost immediately received more than 1,900 signatures. As a result, the House ended up suspending the contract. Still, people from Pulso Legislativo said they’d continue providing their service until someone from the legal department of the House announces the official cancellation of the contract.

The Challenge

The guys from Codeando México teamed up with Intangible — a project started by Fede Casas and Jorge Soto that helps entrepreneurs develop their businesses, polish their code, and grow in their market space for up to six months — to walk the talk. They launched the #app115 challenge that invited hackers to take action: “Create an awesome, simple and useful open source Congress app for the Mexican citizens, make some money out of it and show how technology can bridge the gap between citizens and their representatives,” Codeando México wrote in its post. “Together we can go beyond angry tweeting, towards fixing the world on a Saturday night over some tequilas.”

Winners would receive an iPad mini and a symbolic prize amount of $9,300. How did they come up with that figure? “We wanted to make it 10,000 times cheaper,” says Casas.

Soto contacted Yeshua Sanyasi, one of the parliament assistants from a smaller party, to try to get what they were doing noticed by the Congress. They succeeded and set April 4 as the date for app proposals — just 10 days after they had launched the competition. In all, 173 individuals registered to participate, and five apps were presented. Some were built by teams, but most were developed by guys working by themselves.

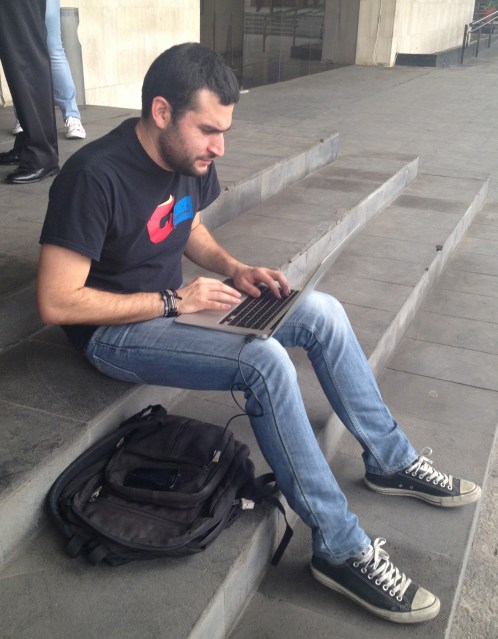

Hacking on the steps of Congress.

The Trip To Congress

I was invited by one of the organizers to watch the presentations and met the participants at the Intangible offices. They were nervous — some of them wore suits, which is very unlike their usual attire — and they were discussing what they thought the event was going to be like. When we arrived at Congress, we went through security and waited an additional 15 minutes while they prepared the room. The hackers used this time to check their apps, take pictures and give interviews.

As soon as we entered the main room, we were greeted by a lawyer and a couple of legislators, one of whom quickly added that this project had been “well received by the Congress” and that they should expect “good representation.” Fifteen minutes before the presentation was to begin, the room was still empty, except for participants, curious onlookers and supporters. Five minutes before, there was around 25 legislators, aids and onlookers. The grandson of the syndicate leader that was very publicly thrown in jail a couple a weeks ago arrived to loudly say hello to everyone and talk about the apps that were live.

We started half an hour late with an audience of around 50 legislators and aids. They introduced the presidium, which was made up of representatives from the party that organized the event and people from the Science and Tech Secretariat. Rodolfo Wilhemy, founder of Codeando México, gave a short speech. He had told me earlier that he wanted to ask for formal support for the hacker community, demanding the creation of a fund and a pipeline of contracts for similar projects. “It will be a white glove slap,” he said. Intangible’s Soto then said a few words, thanking the presidium for the opportunity and finally introduced the participants.

App Presentations

Most teams used the site Curul 501 to obtain the Congressional information with which to populate their apps — partly because the site was at the top of the suggested links in the challenge, and partly because the web page from the Congress is horrible. Of the five apps presented, three were developed for iOS (Diputados, Congreso and Mi Congreso,) and the others for Android (Senado de la República and Actividad en San Lázaro). Each participant had five minutes to pitch their demos. Four of the apps were already in the respective app stores, so the audience could download them and follow the demos.

The presidium.

There was time for questions after each presentation, which is when things got even more interesting. A few of the Congressional representatives had a hard time containing their frustration about the Diputados app, particularly when the group showcased Karma, the app’s ranking feature. It works like this: every bill introduced gives a representative 10 points; every attendance awards three points; and every absence subtracts 20 points. One of the representatives in the audience took the mic and said he thought it was “unfair to be graded.” Another one jumped at this, adding that he had been missing that particular morning because “he was looking at roads.”

It’s clear that this app’s feature was disruptive, having been called unfair and criticized so much. Representatives do have other obligations aside from being in sessions, but there has never been a truly open ranking system where Mexicans can see what their representatives are up to.

Diputados, developed by a workshop from Queretaro and presented by Arturo Jamaica, was chosen as the winner; Mi Congreso (an app entirely developed by Eduardo Blancas by a 20-year-old hacker on his free time from school) was the runner-up. On the spot, the organizing team got Juan Pablo Adame, the Congressional representative in charge of the digital agenda, to agree to this project.

While the $9.3 million-dollar deal was dismantled, Codeando México still has a long road ahead. Remember, Pulso Legislativo plans to keep taking advantage of the bureaucratic process until its contract is canceled — probably in the hopes that the public forgets and lets it go. And although Codeando México managed to hold this competition, there is no official pipeline for the government to pursue further contacts like this one to help engage independent hackers and workshops. If they manage to create that in the next few months, they’ll truly be taking down the Mexican mafia in the best possible way.