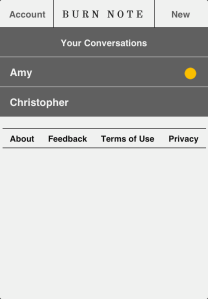

Way back in January 2012, a service called Burn Note launched, aiming to protect your private messages by destroying them after a certain period of time. Right around the same time, the concept of ephemeral messaging caught on with mainstream users with the launch, and mini-controversy, of Snapchat. While Snapchat allows you to send photos and videos that self-destruct, something that was copied executed quickly by Facebook, Burn Note is back and it’s still focused on the straight-up messaging aspect of communication.

Today, Burn Note is launching new iOS and Android apps that have some really interesting features that limit the viewing area of messages to further protect them from getting screenshotted by the recipient. While this might sound overly paranoid, there is absolutely a useful place in the world for technology like this that has nothing to do with sexting.

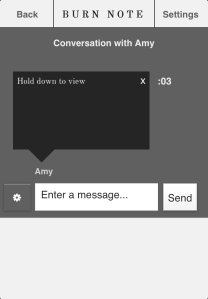

I spoke with Burn Note’s creator, Jacob Robbins, and he explained the new “Spotlight” approach to viewing a message, and it’s really cool. Not only that, but it uses patent-pending technology, as Robbins has clearly spent time on the service since it launched early last year. What Spotlight does is force you to use your finger, or mouse on the desktop, to hover a spotlight over the message, exposing only bits of it at a time. This is great to stop people from screenshotting or copying your messages, as well as discouraging those pesky people that like to read over your shoulder.

Here’s a quick look at how it works:

The messages in Burn Note self-destruct using a timer that starts once the message is opened by the recipient. The service will take a guess at how long the reader will need to read it, or you can set the time yourself. Once the timer expires, your message is destroyed forever. By destroyed, Robbins says that all message data are securely deleted from the Burn Note services and both participants’ devices. This is a key component for a service like Burn Note: If that trust is lost, then so is Burn Note’s chance of success. You can send messages to other Burn Note users, email addresses or send a link to anyone on any platform.

Robbins says the goal of Burn Note is to: “allow online communication at the same level of intimacy as in-person conversation; more personal than sharing on a social site, sending email or using SMS.”

I asked Robbins about some of the potential applications for a service, and messaging platform, like Burn Note and the anti-spy Spotlight technology that he has created:

TC: Can you talk about your experiences with launching the first version of the app?

TC: Can you talk about your experiences with launching the first version of the app?

Jacob Robbins: Launching the first version of the app was surprising. I had not done much research into what people’s first reaction would be when hearing about the concept of ephemeral messaging. I was very surprised to find out that people very frequently connected this technology with a means to complain about their boss or other coworker who was a source of workplace stress. I had not appreciated that this kind of workplace stress is nearly universal, perhaps I’ve spent too much time in the startup echo chamber. But people did not quite understand how the system worked since the first version was very one-directional. They would hear about the initial product and think “Can I tell off so-and-so and have them never realize it was me?” Fortunately they didn’t do that because Burn Note isn’t anonymous but clearly that’s not a good initial reaction and I realized I needed to repackage it to be more similar to an IM client or SMS app — both of which are very familiar conversation tools.

TC: What have you added that you learned from your users along the way?

Robbins: When I was first building Burn Note I was very focused on technology that would let users trust that their messages were not retained on the server. The feedback from users ignored this nearly entirely and instead focused on how they could trust their messages were not retained on the recipient’s side.

Preventing recipients from retaining copies of the message you send them is a cat-and-mouse game where there is no perfect solution since the point of communication is for the recipient to retain a copy of the information in some way (e.g. in their brain). But the larger issue is that the sender often cares about the security of their message more than the recipient and they want tools to help them out. This is why we feel the Spotlight is a good match for the situation. It provides a couple of different benefits in this vein including resisting copy and paste, resisting screenshots and also limiting surreptitious viewing of messages by people nearby to the recipient.

One of the more interesting responses we had was from a hairdresser who, on using the Spotlight for the first time said, “this could be really useful for me when I’m reading messages at the salon so that people can’t walk up behind me and see my conversation”. We hadn’t ever considered the kind of privacy concerns that users deal with when having personal text conversations in a workplace where everybody is on their feet all day and moving around. Breaking the desk/cubicle mindset is important to understanding the real use situations for a mobile app.

TC: Talk about Spotlight. Is this something you’ve been working on for a while?

TC: Talk about Spotlight. Is this something you’ve been working on for a while?

Robbins: We experimented with a lot of different methods for displaying message contents before settling on Spotlight. In one we would break the message into short phrases and display them one after the other as if they were on flashcards. We even tried making a video out of the message which showed a random part of the message in each frame but when viewed continuously you could see the whole message as a sort of jerky static image. In the end the Spotlight method was the one that got an immediate emotional reaction from people when they first used it and that was what sold us on it.

TC: What do you think about other apps, specifically Snapchat, that get a bad rap for the type of messaging you offer?

Robbins: It was interesting to see how Snapchat was covered in the press because a lot of journalists and bloggers clearly did not know what to make of it. The story that was most frequently written was that teens were primarily using Snapchat for sexting but that was pretty transparently not true unless sexting was a daily activity primarily done during school hours in which case school administrators could be expected to weigh in loudly. On the one hand you had very high volumes of usage that were clearly noteworthy, and on the other hand you had journalists pushing out stories saying “the kids are all sexting!” It very much reminded me of Tom Wolfe’s description of the mainstream press grumbling about Beatlemania in the early 60s, complaining about the crowds of screaming teens, calling “I want to hold your hand” “I want to hold my nose” etc.

TC: Talk about some of the usages of the app that you never thought you’d see. Any enterprise usage?

Robbins: We haven’t had any enterprise usage yet that I’m aware of. Part of the challenge of operating Burn Note is that ensuring message contents remain private is the highest priority of what we do and analyzing usage patterns has to take a back seat to that. As a result we get very little insight into what people are using it for. We’re pretty much reliant on anecdotal feedback from customer service and surveys to get use case details, though we do have aggregate totals to measure volume. Earlier this year we had a customer service interaction with a British private investigation firm which is an interesting professional use case but most of the feedback has been from people using it to have conversations with friends and family.

———

This is clearly not an app that’s going to take a chunk of SMS usage away from carriers, but it’s definitely an interesting proposition for those who might be shy to say certain things or just want to bitch about their coworkers without fear of social repercussion. Sure, you could conjure up a slew of uses for an app like Burn Note that are unsavory, but at the end of the day, you could do that for any service.

To appreciate the service for what it is, trying it out is a must. There are situations where I could see myself sending a message over Burn Note instead of SMS or an email, which open themselves up to making their way to the Internet or someone else’s inbox. Sure, we should be able to trust our friends to not do this, but it happens. I’ve gotten things in my personal inbox that were way too personal for my eyes, and I usually say something about it, where most people might not do the same.

If you want to send someone a really private message, maybe something as innocent as how much you like them, a service like this might give you the courage to do so. If your affection for someone isn’t reciprocated, then there’s no harm or foul. Sure, the other person could say to their friends “hey, they sent me a message asking me out on a date,” but without seeing the message, the social fears are limited.

Burn Note’s updated web, mobile, iOS and Android apps are available today.