If you build it, they will come. Perhaps. And only if you don’t chase them away.

Recently Google co-founder Sergey Brin took to the stage at the TED “Ideas Worth Spreading” conference. His idea worth spreading? That cellphones are “emasculating.”

This newsbyte, currently making the rounds, appears here and elsewhere out of context from a much longer pitch for Google Glass, a high-tech monocle that is Google’s eyebrow-raising vision for the next generation of wearable computing. But with reporters there to witness it live, readers appear to have since deemed Brin’s remark the most shareworthy headline of the event. (When asked about the remark’s larger context, Google didn’t immediately elaborate on record.)

With one word Brin appears to have shot in the direction of both feet: both possibly alienating Google’s male Android smartphone customers and offputting women who might otherwise be in the market for Google Glass.

This is a point made clear by close technology follower and Wharton business ethics professor Andrea Matwyshyn, who writes to TechCrunch:

That is a missed commercial opportunity. Women make a large portion of household consumer purchasing decisions in the United States, and they tend to spend equal or greater numbers of hours using technology as do men according to some studies.

In other words, a marketing strategy that positions Google Glass as a “man gadget” potentially alienates half of the consumer base who might have been keenly interested in purchasing the product in the future.

A question going forward is whether women beyond technology insiders like Matwyshyn have even heard about the gaffe, let alone Google Glass altogether. In the meantime, from an armchair perspective, charts from Google Trends shows usage for the “emasculating” search term has skyrocketed, and thousands of references to the quote appear to smear across Google News.

If the first rule of speaking is to know your audience, such a remark prompts questions about whether Brin, and by extension Google, knows theirs. What will Google Glass be used for? The answer seems to be literally anyone’s guess.

In a recently ended contest, Google asked potential Google Glass customers — when “applying” to purchase the $1,500 developer device — to identify and define themselves via the use of a #ifihadglass hashtag on Google+ or Twitter. Thanks to public messages and public APIs, results from the #ifihadglass marketing campaign are in effect transparent.

In order to guess at what Google is seeing in terms of gender breakdown amid this abundance of marketing information, TechCrunch collected close to 11,000 Google+ posts and 22,000 tweets tagged with #ifihadglass and looked at the likely gender of the authors’ first names. The results suggest that if Google isn’t yet worried about encouraging female adoption of Google Glass, perhaps it should be.

Amateur analysis is fraught with guesswork — especially when dealing with gender-by-name, since names such as “Taylor” can be donned by both females and males. To attempt to compensate, a probability for each gender was assigned using census data on how frequently the name occurs by gender in the United States. Names like “Elizabeth” with greater than a 95 percent certainty of being a given gender was assigned to a gender group; mixed names like “Taylor” were compared across genders and become ‘likely-male’ or ‘likely-female’ and grouped together as ‘uncertain’; both never-before-seen and non-names like “JetBlue” get lumped into the ‘ambiguous’ group.

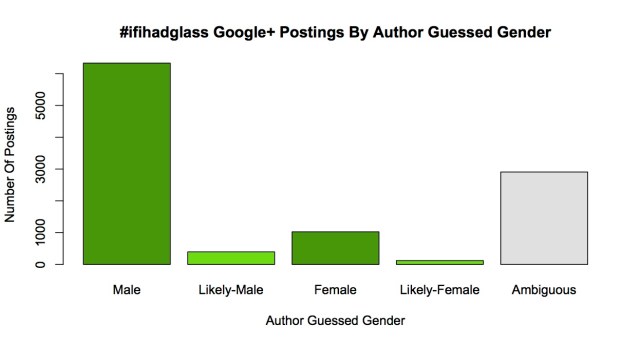

To be taken with skepticism, here’s the breakdown of the TechCrunch analysis of the likely gender of authors of #ifihadglass postings on Google+:

- For the 7,358 Google+ postings whose authors had first names assigned to a gender group, 86% were guessed to be posted by males and 14% by females.

- Including 517 uncertain cases, the numbers water down to 80% male and 13% female.

- Among the uncertain cases, 77% where thought to be ‘likely male’ and 23% ‘likely female’.

- 27% of the overall 10,782 found Google+ postings tagged with #ifihadglass were authored by people’s whose names were deemed ambiguous.

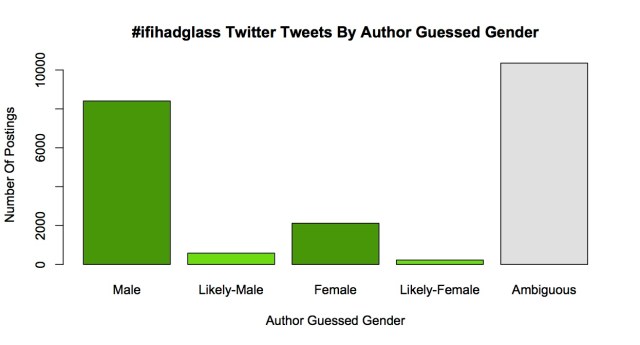

For Twitter:

- For the 10,524 Twitter tweets whose authors had first names assigned to a gender group, 80% were guessed to be male and 20% female.

- Including 807 uncertain cases, the numbers adjust to 74% male and 19% female.

- Among the uncertain cases, 72% where thought to be ‘likely male’ and 28% ‘likely female’.

- 48% of the overall 21,684 tweets found at the time were deemed as authored by someone whose first name was too ambiguous to gender.

Google has a real name policy that makes its publicly findable data quality a little better than Twitter’s. The gender breakdown of Google+ users is uncertain and so a good baseline of over-/under-representation by gender cannot be established across both Twitter and Google+.

Any uncontrolled or publicly sourced data are suspect and the underlying dataset here is not an exception. Another possible problem is that kind of hashtag analysis also embraces the “no press is bad press” mentality and includes those freeriding with their own marketing efforts and and those just having some fun.

Despite all the caveats, the numbers present a strong argument why Brin might be tempted to play up the “masculinity” angle for Google Glass: among early customers talking about “#ifihadglass,” about four out of five appear to be men.

The other edge to this truth is that while it might be tempting to preach to the male demographic choir, in fact Google should perhaps be doing the opposite: encouraging early adoption among women. Without a representative customer base selling the first generation of this technology to their peers, Google could end up with the next Segway.

An informal mining of the many uses suggested by these prospective customers — among them, health and recreation (traveling, coaching, workout, biofeedback, biking, baby care), health and emergency services (emergency care, diagnosis, surgery), reference (instructional material, study aids/practice, translation, search, research, image recognition), location (GPS/maps, directions, traffic), communication (reading, sharing, teaching, training, tours), productivity (note taking, tasks) and cooking — none but the very visually- or manually intensive applications scream for the immediate abandonment of the ubiquitous and “emasculating” smartphone. In this case, as in others, data seem to back common sense that it’s not a great marketing strategy to alienate a critical and already-trailing customer segment.