Entrepreneur-turned-investor is a classic story arc in Silicon Valley but recently the plot has earned a twist. Certain operators are foregoing the traditional path of joining a traditional VC to instead create a studio-like holding operation. By doing so, they remain engaged with the grit and grassroots challenges of building a startup. They remain company builders.

John Borthwick and his New York City-based technology studio, Betaworks, was one of the recent pioneers of what Borthwick calls a “new asset class” in the VC world. And Bill Gross started this in the nineties with IdeaLab. But we’ve seen many others follow.

Twitter co-founders Ev Williams And Biz Stone launched the Obvious Corp.; Mike Jones and Peter Pham run the LA-based studio Science; Max Levchin debuted his R&D lab HVF; Snapfish founder and Mayfield partner Raj Kapoor is in the process of launching his studio cofounder.co; Michael Birch has Monkey Inferno; Groupon co-founders Eric Lefkofsky and Brad Keywell, along with partner Paul Lee, are incubating ideas and startups at Lightbank; Kevin Ryan operates AlleyCorp; and most recently we heard that entrepreneur and Menlo Ventures partner Shervin Pishevar is creating is own startup-creation venture, Sherpa. Even VC giant Andreessen Horowitz is building an army of marketers, business development execs, recruiters and more to help aid in the creation of startups.

Each model differs slightly. Some take bigger chunks of equity than others. Some of the studio creators take co-founder titles on certain startups. Many studios not only create and incubate ideas in-house, but also make seed-stage investments in startups outside of the company. But at the heart of what each of these studios is doing is using entrepreneurial expertise and in-house resources to help generate ideas and build companies at scale.

As this trend takes off, it raises the question why?

Speed

Lee, who has helped Lightbank incubate a number of ideas including loyalty startup Belly, explains that because it is so easy to build startups these days, that there is a need for models that allow companies to leverage certain functions like sales and marketing, hiring, legal and more. It’s important to note that this is probably one of the biggest differentiators between studios and accelerators.

If the studio has some of these functions built in-house, then startups can actually leverage these repeatable services and scale more quickly with less capital. In Lightbank’s case, the firm has built and scaled sales teams across a number of industries and companies and can help startups quickly manage this area.

Borthwick echoes Lee’s thoughts on the value of a shared platform of data, analytics and monetization tools. Betaworks has a layer of tools that its companies, which include Chartbeat, Bitly and others, all use. He compares this to the movie studio model, where companies like Disney and Universal create individual movies but have a layer of services in-house that promote films, and provide other functions across these various content plays.

LA-based Science has a similar approach to Betaworks and has built a number of B2B companies that can provide its other consumer-facing startups with marketing technologies. TripleThread, which launched in November and powers personalization for styling and clothing companies, supports another Science company, Fourth and Grand, which offers a personalized styling service for men.

Andreessen Horowitz has been building its layer of services for startups by hiring an army of talent to help portfolio startups. The firm’s partner, Margit Wennmachers, explains that Andreessen sees entrepreneurs as the epicenter to an idea, and works on helping with everything else that the entrepreneur doesn’t have time to do. So if an entrepreneur is a coding genius, Andreessen will work on helping with go-to market strategies, marketing, recruiting, and more. The firm has developed a network of talent in-house to help with this. Andreessen just brought on Wildfire product exec Tom Rikert and Twitter marketing exec Elizabeth Weil.

While these services help startups get their products built, shipped and marketed in a speedy fashion; speed also has its benefits when things don’t go so well in development of an idea. The ability to quickly scale ideas can also be advantageous when an idea doesn’t work and you need to shut it down.

Borthwick explained to us that part of what makes this studio model work is that there’s the opportunity for rapid experimentation and company development. “Failure is part of the model. The traditional VC model is predicated on the fact that failure happens in the marketplace. But our model is a more flexible platform for innovation. If things don’t look like they will work out, we can easily pivot because there hasn’t been as much capital and investment put in,” he says. “Death and breakage is part of the system.”

“Parallel Entrepreneurship”

Ev Williams refers to this model on a Branch (which is a communications product that is investment and part of Obvious) thread from last year, as “parallel entrepreneurship.” In a lot of ways, this seems like an accurate description of these company building studios.

Stone and Williams, Kapoor, Borthwick, Pishevar, Jones, Levchin and others have all had experience being able to build and grow startups. They can all work in tandem with talent in-house, and help this new generation of entrepreneurs turn ideas into actual businesses. The benefit for the company builder is that they can scale their experience across a number of startups and ideas, take a hands-on approach to helping in product and engineering and take equity stakes in each. The new, young entrepreneur gets to learn how to build a company from someone who has had success and can scale more quickly. As Pham puts it, “collective knowledge is always better than singular knowledge.”

Kapoor, who announced his departure from Mayfield to create his own startup studio, explains that an experienced entrepreneur can give founders an advantage by being able to short-circuit lessons that the entrepreneur learned when he or she founded a company previously. Kapoor co-founded and was the CEO of Snapfish, which was sold to HP for $300 million. His model at Cofounder.co centralizes around co-founding startups and helping in all areas of the company including financing, recruiting, strategy, product development and mentoring the CEO. While he hasn’t yet officially launched, he explained that he found the traditional VC model doesn’t allow VCs to go as in-depth in the trenches with entrepreneurs as with the studio model.

His view is that entrepreneurs are looking for help as much as money, especially at an early stage. “Entrepreneurs are open to and expecting help that goes beyond just investing. In the traditional VC world, it’s done it through mentors and advisors,” he says. “But it is very difficult for someone who isn’t really close to the company to add value on a regular basis.”

Lee adds that for a young entrepreneur who may not have a lot of work and technology experience, it is still extremely hard to build a company on your own, even in a traditional accelerator or incubator. He feels that the company-building model fills a gap in the market.

He also points out that there will always be a class of entrepreneurs who don’t need to participate in the studio model. “There are some entrepreneurs who don’t need to strongly lean on the learnings of those who have succeeded previously, but there are some founders where it makes more sense to have a stronger network surround them,” he says.

He also points out that there will always be a class of entrepreneurs who don’t need to participate in the studio model. “There are some entrepreneurs who don’t need to strongly lean on the learnings of those who have succeeded previously, but there are some founders where it makes more sense to have a stronger network surround them,” he says.

In his experience, Borthwick notes that there are certain types of entrepreneurs that the studio model scales well for, and this sort of partnership isn’t for everybody. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all model for the entrepreneur.”

Another area where the studio model can differ from traditional VC investment or even accelerators is in the equity handout. Science takes mid-to-high, double-digit equity in their startups (compared to Y Combinator’s 7 percent). All models are different in terms of how they are breaking down equity allotments, but it can be daunting to give away that amount of equity and it begs the question of whether this is entrepreneur-friendly.

But clearly as more and more entrepreneurs flock to Betaworks, Science, Obvious Corp. and similar companies, it’s clear that some entrepreneurs see that there is a tradeoff in equity versus the value that people like Williams, Jones, Stone, Borthwick, Pham and others provide. Lee says that this exchange may make more sense for younger entrepreneurs who see value in the experience of working under these leaders and founders.

However, it’s still early days and too soon to determine the longevity of the companies that emerge from these studios, as well as how the entrepreneurs that these studios are nurturing will perform in the greater technology market.

The other question is whether this new model will produce the sort of iconic VC firms like Sequoia and Kleiner Perkins. This will largely depend on whether the bets that these studios and company builders make turn into the next Googles, Microsofts or Facebooks of our world.

Borthwick is confident that this model is succeeding in the seed-stage investment world. He notes in his yearly letter to shareholders. “Our approach allows us to achieve a velocity that other parts of the seed and VC stacks find hard to achieve…betaworks has played a part in the emergence of this larger, more diverse, more independent, and loosely-coupled seed financing marketplace; we believe its existence and growth tends to validate the betaworks model and its emergence as a new asset class.”

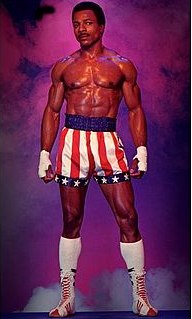

In a way, company building allows the experienced entrepreneur to keep playing the game. It’s like when Apollo Creed retired from professional boxing, but then decided to coach Rocky Balboa against Clubber Lang. As Pham explains, for some founders this is the best of both worlds. They get to raise a fund and invest in people they believe in, but also keep their hands dirty in the nit and grit of startup creation. It’s the classic story of an entrepreneur who has been through her own roller coaster ride and now wants to invest in others who have an appetite to do the same — only now, she wants a seat on the ride.