When Netflix bid on and won the rights to House of Cards back in 2011 – buying the show before it was shot and committing to two full seasons – it made headlines. And with good reason: Funding such a high-profile slice of original programming – with David Fincher and Kevin Spacey on board — cast Netflix in a role typically occupied by HBO.

Rumours of a $100 million+ price tag for HoC were bandied around. An AllThingsD source suggested a minimum of $3 million per episode – putting the total cost at $78 million at least. Netflix has not publicly confirmed how much it’s spending on the show, although a WSJ source “familiar with Netflix’s plans” claimed the cost would likely be far less than $100 million.

Whatever the final figure, Netflix has rolled out a red carpet of grand claims regarding what the show means for Internet TV. “We believe that February 1st [the date the first season of HoC was put on Netflix] will be a defining moment in the development of Internet TV,” it proclaimed on an earnings call last month. “For viewers, Internet TV is a better experience because of the freedom and flexibility it provides, and in the case of Netflix, the lack of commercials,” it added.

Of course it’s Netflix’s job to talk up Internet TV since that’s its business. But beyond the ability to watch a new show at your own pace, without being tied to a linear multi-week episode release schedule, is HoC really so revolutionary?

Having watched the entire show I am struck by one thing: HoC is chock full of commercial content — far more than I can recall seeing in any recent, or not-so-recent, TV show. For Netflix to claim that Internet TV lacks commercials is, when it comes to this particular slice of original programming, disingenuous at best.

Products are not just placed incidentally and occasionally in the background of HoC, they are a constant frame around the action and a deflecting focus for the director’s lens. And worse: At times brand interests clearly hijack portions of the plot, character arcs, scripting — the works.

Apple products dominate the show but it’s not the only brand in play, with BlackBerry, Canon, Dell and Sony also getting a slice of air time (to name just the brands I immediately noticed). Some of these product appearances are fleeting. Many are not.

At various points the show feels so saturated with commercial content that describing the occurrence as ‘product placement’ feels inaccurate. It’s more like product co-production. And that is very interesting indeed. It suggests that Internet TV-funded original programming, at least on this grand scale, may not be quite so revolutionary after all. Not in a commercial-free sense, in any case.

Netflix does not have the resources of Time Warner-owned HBO. In its Q4 2012 earnings last month, Netflix reported revenue of $945 million for the quarter versus $3.7 billion for Time Warner’s networks business alone in its Q4. Funding original programming of this calibre is new ground for Netflix, and new ground it is having to stretch itself to break. “The goal is to become HBO faster than HBO can become us,” said Ted Sarandos, Netflix’s chief content officer, speaking to GQ earlier this month.

As AllThingsD’s Peter Kafka noted at the time Netflix was negotiating the rights to House of Cards, the company can afford to make the show — but it can’t afford to make “many” such shows. Not “unless [CEO Reed] Hastings has figured out a way to lay off some of the costs with a partner, or work some kind of production magic.”

Well, one way to lay off some of those costs might be to cut considerably more product-placement deals. It effectively means partnering with brands to give them advertising-style, product-showcasing opportunities that involve the main characters and are smuggled into the plot to act as embedded, concealed commercials.

When I asked about product placement in HoC, Netflix declined to comment. Nor would it discuss how involved it was in producing the show. The names above the show’s door are the indie studio production house MRC and director David Fincher. But there’s no hiding all the brands’ starring roles. Or the fact that Netflix bought the show before it was shot — giving it the opportunity to have input in its production. (There’s a fascinating study waiting to be conducted that details the amount of air time the Apple logo alone gets in HoC or deconstructs scene composition and camera angle when the various brands are onscreen.)

As Internet TV — and DVRs — let more viewers edit out commercials, they may well also be driving more commercial content inside the frame where viewers can’t avoid it. A Bloomberg Businessweek story from last year, on Hollywood’s love affair with Apple products, cited research from Nielsen showing how Apple product placements have risen in recent years. Cupertino’s gadgets were discussed or shown 891 times on TV in 2011, according to Nielsen, which is up from 613 in 2009. HoC alone will surely help ramp that figure up considerably in 2013.

Apple has said it does not pay for placements. Rather it apparently supplies its kit to producers for free in exchange for the free marketing — in other words, a barter deal. Money or no money, Apple evidently takes product placement very seriously. During last year’s big U.S. Apple v. Samsung patent trial, Cupertino’s marketing chief Phil Schiller revealed the company has an employee who works closely with Hollywood to ensure its gadgets get on the big screen. (Apple did not respond to my questions about its product placement T&Cs.)

So, while it’s unclear whether Netflix can book actual revenue from product placements inside HoC (Apple may refuse to get out its checkbook when producers come calling, but other brands with less to offer may have to pay) it can use product placement to reduce overall production and marketing costs. Indeed, that’s exactly what Netflix appears to be doing.

It also looks like there’s some cross-business back-scratching going on, too — Sony’s PS3 and PS Vita, which both feature in the show, can stream Netflix content (as can Apple products) so there are certainly mutual interests (“business synergies”) in play. But being under more pressure to keep costs down than its traditional rivals, Netflix appears less able to prevent commercial interests from leaving their fingerprints all over its content.

In other words: not so revolutionary now.

Product Placement Up Close

For readers who don’t mind a few plot spoilers, I’m detailing several examples of the commercial content embedded within House of Cards below (with screen grabs) to illustrate how not all product placements in the show are equal. And to shine a light on the very worst example (see: ‘The Ugly’).

Spoiler warning: stop reading now if you haven’t binged your way through all 13 episodes yet. You have been warned!

The Good Just About Tolerable

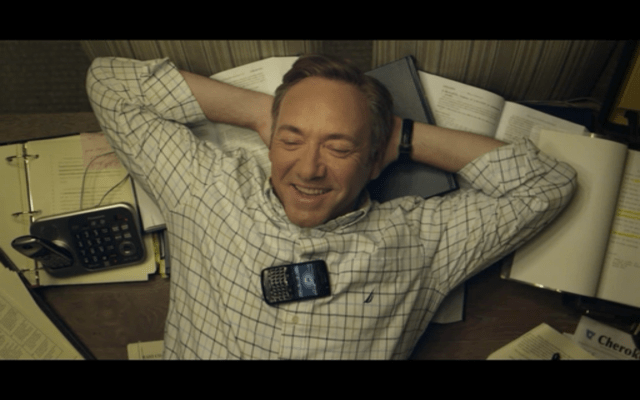

Lots of folks use smartphones in their daily lives. Plenty of them even use iPhones, especially in the U.S. So although it’s a little creepy that almost everyone in House of Cards uses an iPhone – and some characters even have his ‘n’ hers black ‘n’ white matching iPhones – this is just about tolerable.

At least the show includes an alternative: BlackBerrys, which are typically used as work phones by the politicians. So far, so kinda fair. That said, I couldn’t spot one Android phone in use. So it’s definitely a skewed view of the smartphone market.

Interestingly a generic-looking phone (below) appears in a key scene in the first episode – along with graphical overlays to depict SMS back and forth (later episodes default to iOS text screens) – but perhaps these scenes were shot before the product-placement deals had been hammered out.

The Bad

As mentioned earlier, Apple products are by far the most dominant brand on the show, with the full spectrum of iDevices represented — from iPhones, to iPads, to iMacs, to Macbooks and even Apple’s distinctive white earbuds getting screen time. Elsewhere Dell gets to sneak in a couple of PCs and Sony gets in on the gaming side, but this show feels like it was made on location at 1 Infinite Loop. The cumulative impact undermines the atmosphere of the show, giving it the feel of an Apple lifestyle advert and creating a credibility barrier between the content and the viewer.

In addition to surreal brand homogeneity, in many instances the branded products do not just crop up casually. Often the writers appear to have gone out of their way to create appearance/citation opportunities – whether it’s using a branded product in place of a generic one or scripting the show to deliberately draw more attention to the product and its functionality.

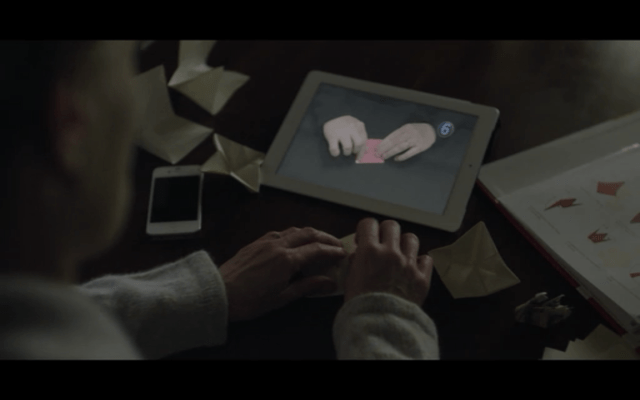

For example, characters use their iPhones as torches, and more than once there’s a mention of how so-and-so doesn’t need a wake-up call, as their phone doubles as their alarm. In another scene, a character is shown trying to learn origami by watching a video on an iPad.

In another especially naked product spot, a character arrives in another’s flat and points out a device lying on the table with the comment: “Is that a PS Vita?” He then asks what games it has (“Everything,” says the other character), before going on to talk about how he already owns a PS3 and ending the sequence with “I gotta get me one of those [PS Vita] for the car.” And thus ends the embedded PS Vita ad.

Sure, people use gadgets IRL but people do lots of things. House of Cards doesn’t spend any time showing characters clipping their toenails, but it does spend a lot of time lingering on electronica — with scene composition, camera angle/movement deliberately chosen to frame and showcase the branded goods.

Whole plot points also often hinge on technology – in a way that makes you suspect a portion of the action is being dictated by the commercial interests of the brands in play. Sometimes the tech elements of the plot fit with the characters in question; other times they definitely don’t. A middle-aged congressman is shown more than once letting off steam by blasting some bad guys on his PS3. To my eye that example is borderline plausible — and at least serves to illustrate his inner aggression.

Likewise, in another scene a journalist whips out her iPhone to post to social media that she’s just been sacked – which in turn leads to her boss getting the boot (what an advert for an iPhone!). She also uses her iPhone to take notes for a story and to interact with a potential source. These instances, while still clearly product placement, at least seem true to her character – as a young, digitally switched-on tech user and journalist.

But in another scene a grieving mother from a town in the deep south of the U.S. who has just lost her daughter in a driving accident is depicted using an iPhone to show photos of her (now dead) daughter. Here, the iPhone sticks out a mile — perhaps because grief is such an odd context for an advert.

The Ugly

The most gratuitous example of product placement in House of Cards is actually better termed “character placement.” The character in question – and a chain of key scenes in his plot line – are entirely dictated by product. Of course I can’t prove this – Netflix declined to comment – so I’m speculating based on my experience of viewing the show. But so naked is the commercial agenda at this point that I would argue all it takes is a pair of eyes to deconstruct the interests driving the script.

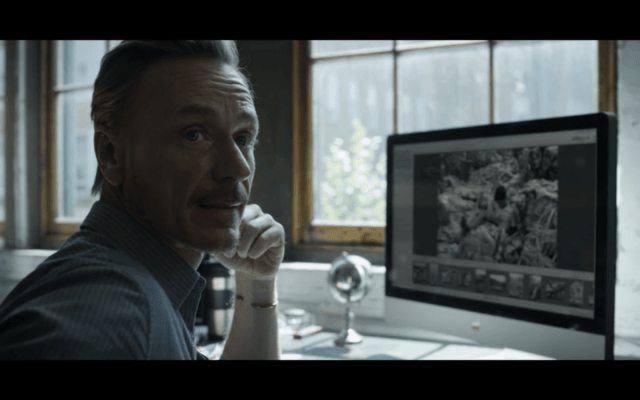

Firstly the character’s profession – a photographer – could well have been chosen purely to showcase two key products (made by Canon): a camera and a photo printer. It’s not especially important to the overall plot that he’s a photographer – lots of other professions would do. But it’s vitally important to Canon that he is since he is their brand evangelist.

This character lives the kind of aspirational lifestyle advertisers love to depict, complete with an open-plan New York loft apartment-cum-studio that looks like it was lifted straight off the pages of a magazine. He’s also the sort of fun-loving, free-living free spirit who can fill a room with attractive singleton friends on cue the moment he feels like having a party. These anonymous friends are the kind of tasteful hedonists you routinely see laughing and dancing in alcohol commercials — i.e. never getting too drunk, never making a scene, never saying anything. They are not characters, they are window-dressing for his aspirational lifestyle.

The most gratuitous sequence in this character’s plot line involves an apparently spontaneous morning-after walk in the park between the photographer and his love interest. The scene itself feels awkward enough, since it’s impossible to feel any emotional attachment to a walking advertisement, but to make matters worse he’s brought along his gigantic DSLR Canon camera.

The female love interest then takes the camera off him, zooming in on a woman sitting on a bench in the distance and taking a perfectly crisp shot despite being a total camera amateur. This sequence is an undiluted Canon commercial. But there’s more. Back at the apartment, the pair are shown printing out (from a Canon photo printer) the last page of a gigantic photo-mosaic of the girl they pointlessly took a picture of in the park – a woman who has zero relevance to their life — and laying it out on the floor. Look, it’s saying, look at the PRODUCTS.

The long and short of all this is that people don’t do that. Adverts do. This entire sequence is so nakedly commercialized it’s an insult to the intelligence of the viewer. And since it lacks any emotional impact (these are adverts, not characters, so we can’t feel anything for them) — its narrative purpose is also derailed at what should be a key plot point in the show.

We learn nothing about the female character — who is central to the overall plot, and has left her husband to be with this man — because we’re too busy being told about how great Canon’s camera is and how rad its line of photo printers is.

The sequence is a commercial cul-du-sac where the products are allowed to switch places with the stars and the integrity of the show comes tumbling down.

There is only one word for this — and it’s definitely not “revolutionary.” Take it away, David Lynch: