To prevent people from thinking Facebook apps are losing users when there are bugs in the user count data it reports to services like AppData, starting January 16th Facebook will only report user counts in much broader tiered thresholds instead of to the nearest 100,000. However, it will start reporting App Center rankings. The change follows a disastrous misinterpretation of Instagram data over the holidays.

Facebook explains that an app with 1,100,000 monthly active users (MAU) will now be shown as the #300 largest app by MAU and as having more than 1,000,000 MAU.”

Trouble With Transparency

Until now, Facebook app-growth tracking services, such as Inside Network’s AppData, could pull from Facebook the monthly, weekly, and daily active user counts to the nearest 100,000 of any app on its platform (except for Facebook’s own apps). The public and a developer’s competitors could use these services to monitor an app’s rise and fall. It provided great transparency to the Facebook app industry, but it also caused some problems.

Sometimes the transparency made it tough for apps to make changes, because if their experiment failed and user counts dropped, the world would immediately know. This may have discouraged innovation.

The other big issue was that if Facebook had an error when reporting user count data, or a tracking service had trouble recording the data, apps could end up showing zero users or the same user count as the previous day instead of their real stats. This could cause an app’s monthly active user count to plummet. Journalists unfamiliar with app-tracking services would sometimes jump to the conclusion that people were abandoning an app when really it was just a data-reporting error.

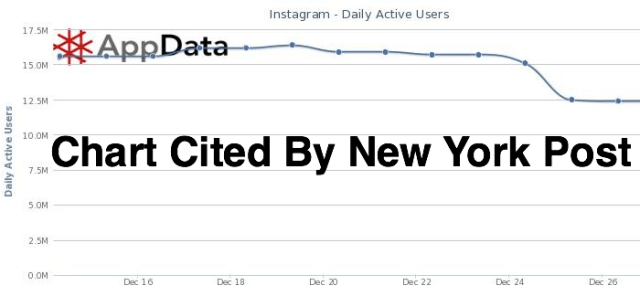

This came to a head over the holidays when a dubious New York Post article said Facebook’s acquisition Instagram was hemorrhaging users after scaring them with a privacy and ads policy change that it later went back on. Facebook denied the usage dip, and we and other outlets made strong arguments for why the Post’s claim that Instagram had lost 25 percent of its users was wrong and a clear misinterpretation of AppData, which only reports logged-in Facebook users, not all users. The scare temporarily sunk Facebook’s share price by a few points.

Following that fiasco, Facebook yesterday stopped reporting data on Instagram. That was a predictable change considering Facebook doesn’t publicly report user counts for any of the other mobile apps it’s built, such as Facebook for Android, Facebook Messenger, or the new Poke app.

Blurring The Line Graphs

Now Facebook has announced it will roll out a change to what it reports in the API in a move it believes will protect app developers and give them more freedom to iterate with their products. Instead of data to the nearest 100,000 users – such as saying an app has 1,200,000 users – Facebook will only report that an app has more than 1,000,000 users. This should obscure the user count impact of temporary glitches in data and changes to app designs. In consolation, Facebook will now report the App Center ranking of apps.

Unfortunately, the lack of granular data could hurt businesses like Inside Network (where I worked before TechCrunch), which operates AppData. Less precise data might not be able to command as high of a subscription costs from developers who pay for historical data on all apps, beyond the most recent 30 days of data that is publicly available for free.

On the other hand, while Facebook’s own apps are immune to the changes as their stats aren’t reported, the changes could still assist the social network and its biggest partners. If a popular Zynga game suddenly loses users or a data-reporting error would have made it look that way, it will be harder for the public to tell. Since Facebook’s success is in some ways tied to the top apps on its platform, user-count obscurity could help Facebook by hiding failures.