The social layer has settled on the web like a dusting of multicolored snowflakes, gracing every story with a little menagerie of sharing counts and buttons. Once basic standards of content publishing were established, basic standards of sharing had to be as well, the internet being as it is a medium of information transmission. First you get the content, then you move it around. We’re still working on the moving around part.

Another layering we’ve seen is the layering of the internet onto the real world. Location-based networking, maps, deals, all that. As soon as we had the ability to tell the world where we were, that information was naturally integrated into our services.

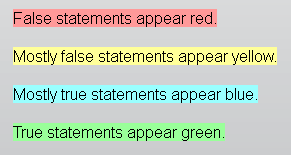

Yet another combination is emerging: the layering of reference and context onto the information you read. What this even comprises is difficult to say exactly, but MIT Media Lab grad student Daniel Schultz (@slifty) has one idea: a browser script that automatically checks what you’re reading against reliable, substantiated facts. It’s a simple idea with innumerable approaches, problems, and implications — which means we’ll probably be dealing with it for a long time.

Some things like this already exist. For instance, many websites have add-ons that let you, say, double click on a word to have it defined for you. Simple enough: send the word as a query to a database, and display the result. Not so easy when you want to evaluate a statement like “Senator Durbin has consistently argued that the US should have a stronger economic presence in the Balkans.” It’s a minefield of potential stumbling blocks, open to interpretation and argument.

Yet who will deny that a plug-in or service that takes that statement and tells you the degree to which it can be considered true would be immensely useful and hugely popular? For this reason it’s worth it to someone to do the legwork. But the challenges and implications are serious.

Yet who will deny that a plug-in or service that takes that statement and tells you the degree to which it can be considered true would be immensely useful and hugely popular? For this reason it’s worth it to someone to do the legwork. But the challenges and implications are serious.

Schultz’s script, which he calls “Truth Goggles,” (not Googles, as I originally wrote) is still in a very early state. At the moment he is using Politifact and NewsTrust APIs as his sources, and has a system of breaking down articles into snippets, which are essentially chunks containing a verifiable claim and some context.

He acknowledges right away (in an older blog post) that language is a problem. He advocates a “hybrid” approach in which the claim is interpreted and checked if necessary with the user, who will be able to work out any grammatical quirks, triple negatives, or other linguistic hobgoblins that could obscure the meaning of a statement. So then you have an intelligible claim that can be compared to the data.

Or do you? Part of political speech is the slipperiness of words. What is “consistently” or “stronger” to the reader? To the senator? To Politifact? Unfortunately this may be a fundamental shortcoming of the system. But facts are facts and fiction is fiction, so the tools will be welcome however limited they are.

What I wonder, however, is whether such a system will in fact lead to a better-informed reader. A major problem today is how people limit their news sources to those that confirm their existing biases. We’re all guilty of it to some degree, and while we may not all listen to Fox News Radio six hours a day, our constellations of information sources are very rarely broad enough to dispel our own pleasant prejudices and established ideas. Will an automatic fact-checker change this?

At first I thought that competing services will arise for different constituencies. One drawing on Wikipedia and one on Conservapedia, for instance (an extreme and unlikely example). But the point of Schultz’s work, and of the others that will surely follow it (indeed those that have preceded it), is to completely eschew political fiction (the mythology and rhetoric surrounding people and issues) and apply itself only to political fact. Surely, although there is political capital involved, the number of Occupy Wall Street protestors at a given march can be accurately estimated. Hopefully both the low and the high estimates would be flagged as inaccurate, with a citation. Will readers accept this affront to their dogmatic sovereignty? It’s going to be kind of a change in the way we perceive information, that’s all we can say right now. The habits of users, much less their thoughts and ideas, aren’t the easiest things to predict.

My best guess is that this will be a growing part of the behind the scenes internet services industry. Google would be a natural contender, indexing as it does much of the data one would need to reach a reasonable judgment. But Google isn’t really in the judgment business. Sure, you’ve got their “best guess for Patrick Swayze age” if you search for it (59!), but evaluating natural-language claims, political or what have you, doesn’t seem like their business. They store and index data and surface what you’re looking for. I think it will be a startup, or someone in academia like Schultz, who provides the first germ of this and starts a movement, though his own contributions may in the end be minimal. The competition will, hopefully, be based on the accuracy of their evaluations, just as the search engines competed on speed and simplicity, or device makers on build and design.

Ultimately it will just be one of many custom layers we put on the web. On top of a story, this one for instance, you already have a navigational layer, an advertising layer, a social layer, and perhaps another layer on top that you’ve added yourself, changing the typeface, altering or removing one of the layers. That you will have a fact-checking layer in the fulness of time is a certainty, but the its creation and tooling will take as much time and effort as have the others. Will it be user-driven? A site? A service? Browser-based? Site-based? Private? Open? Probably all of the above.

Schultz hopes his work will be in usable form before the next presidential election, and while his thesis focuses on applying this fact-checking work to the written word only, but he mentions to the Register that the acceleration of web services means that the interpretation of spoken statements, say in a political debate or TV ad, could also be on the horizon.