Editor’s note: Contributor David Kirkpatrick the author of The Facebook Effect and founder of the Techonomy Conference, taking place Nov. 13-15 in Arizona.

It’s no secret to most readers at TechCrunch that technology is changing the world. Unfortunately, there are a surprising number of people who don’t get it. Many of them, even more unfortunately, are important leaders in business, other powerful institutions, and⎯most⎯governments. To meet the challenges that face us⎯whether as leaders of organizations, as leaders of countries, or as the global community addressing our collective challenges⎯we will only be successful if we unreservedly embrace technology and innovation as essential tools.

For those of us who believe in the vast potential of technology to solve problems, it is both an exciting and a frustrating time. The world’s people are embracing cellphones. More than two billion people use the Internet. Facebook continues its extraordinary user-empowering spread, and the Weibos fill a similar role in China. Advanced companies around the world are redesigning their systems and management to accommodate the new realities of a flattened, technologized business environment. The people of the world have recognized that technology can alter and improve their lives.

Those tech-empowered billions in the developing world will not be satisfied languishing in second-class status. They know about what we have in the developed world and they want more of it for themselves. Fair enough. But how can they get it? How can access to food, shelter, transport, healthcare, and education expand rapidly enough to satisfy the justifiable demands of the world’s people? How can we produce enough energy for a globally-rising standard of living without choking on the fumes? And if we do not succeed in doing so, what are the consequences for global stability? What happens to the world if the scales of wealth do not begin to balance? At present we are not leveraging our resources quickly enough⎯or efficiently enough⎯for all the planet’s people.

Worse, the world lacks enough leaders who understand the potential for new, technology-driven solutions for global problems. To the degree that there is such leadership, it is concentrated in the business community. But even there, an understanding of tech’s potential is disturbingly uneven. Some companies thrive by embracing new methods of marketing, managing, developing products, and engaging with society. Others, by contrast, steadfastly operate in the old ways.

Compounding the complexities is a growing geographic disequilibrium. The U.S., Western Europe, and Japan dither over how to address their severe economic problems, often beset by political gridlock. China, by contrast, with almost one-fifth of the world’s people, forges ahead, installing high-speed trains, energy-efficient power plants, and planned cities. China just does it, democracy be damned. This is unnerving to the rest of the world, which cannot help noticing that China’s economy, along with India’s, Brazil’s, and a few others, isn’t enduring the same economic malaise.

Despite all, there is great cause for optimism: technology writ large—not just IT and the Internet but energy tech, biotech, civil engineering, and science-based progress generally—can revitalize growth and help create a more just, interesting, and prosperous world.

In effect, the fastest-growing resource in the world is computing power and storage. At a time when resource consumption is growing faster in general than resource production, it is incumbent upon all leaders to take advantage of the resource that technology presents us. The countries where that is understood are the ones investing aggressively in technological R&D and in education, especially for science, math, and engineering.

It is in large part the fear that existing resources cannot match human needs that drives the thick cloud of pessimism that prevails today in the world. The Greeks may no longer be able to retire young, enjoy their social democratic benefits, and still pay their bills, because there is not enough wealth to go around. Italy may follow, and some say France could be next. What if we closed ranks around what we know technology can do to improve the efficiency of literally everything? What kind of world could we create?

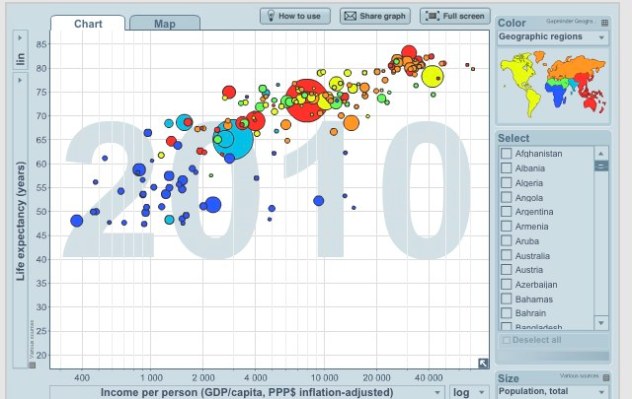

Technology-driven progress is rapidly reducing the global economic divide. This has in fact been true for a long time. If you doubt it, go to gapminder.org and look at the data. (Load Gapminder World, watch the animation of “Health and Wealth of Nations,” and be amazed at the progress.)

Those of us who are technological optimists also see plenty of ways that tech can help enormously with our other grave challenges⎯climate change, cultural misunderstanding, food shortages, inadequate housing, antiquated transportation, and reliance on unsustainable energy sources.

Change from now on is likely to be bottom-up—driven by people empowered by iPhones and Android devices, and by Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Google. It is a new environment for business and for government, and our transition into it is fitful, incomplete, and sometimes frightening. But people are not going to accept the old answers. It is an enormously exciting time. Tunisia was exciting. The cost-of-living protests in Israel were exciting. And both the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street are exciting. All these developments show that ordinary people are paying closer attention to what’s happening in the world, and demanding more from their ostensible leaders. People no longer feel powerless and they are taking action.

The most exciting thing about technology-based development is that it is not zero-sum . Rapid progress in other parts of the world does not mean a decline in already-developed countries, though that is what is more or less happening at present. We have been given a great gift by the exponential rate at which technology improves, undergirded by that old standby, Moore’s Law. As the speeds and power of hardware improve, we can do more with software. With better software we can design better and more efficient vehicles and buildings and cities and healthcare systems and chemical plants.

Despite all our optimism, tech is no panacea. There are real and troubling questions emerging globally about the impact of tech on jobs, for example. It seems more and more likely that while technological progress improves productivity, global GDP, and aggregate social wealth, it will replace more jobs than it creates. Separately, security concerns are growing almost as fast as new technological capabilities. We can see a new world of efficiency and connectedness coming into view. But there is the real risk it could be undermined or even stopped by those who do not want global prosperity⎯be they criminals, terrorists, or renegade governments.

But if all of us who believe in technology’s promise organize our voices more effectively, and work together to understand and exploit its macro impact, there should be wonderful days ahead for the world. Our job is to keep pointing a big neon arrow towards technology as an underutilized tool. There are plenty of reasons to be an optimist in a pessimistic time.