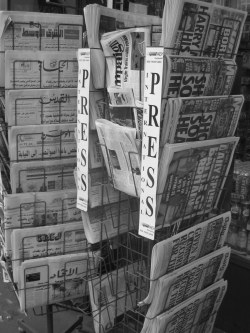

A few nights ago, I was discussing with a friend the practicability of putting content behind a paywall. He felt it was an outdated notion and that advertising or some other method would pay. I disagree. Despite recent setbacks, like the decimation of the Times UK’s readership during their paywall experiment, I think that the paywall will eventually succeed, and even thrive — but the advances and sacrifices necessary to make that happen aren’t likely to happen for at least a few years.

Consumers are wary, for good reason, of paying for content online, for the obvious reason that it’s usually available elsewhere for free. Even “exclusive” items are usually duplicated shortly being made available. Publishers and content providers are scrambling for ways to retain their status as news-breakers and innovators — things worth paying for. But miserly consumers and new rules of distribution mean that things must change. The way I see it, the future may be free, but somebody still has to pay for it.

What first needs to be established is a reliable, secure, and convenient electronic wallet system. The big wireless carriers in the US are working on a mobile one called Isis, but the web is a different story and PayPal isn’t cutting it any more. Whether PayPal or Apple will slim down and make themselves more ubiquitous, or an upstart will arrive and send the incumbents sprawling, we don’t know any better than a coin flip right now. What is certain is that in a couple years, we’re going to have single-click secure payment systems with low enough overhead that you can safely charge a nickel, and people will gladly pay it. How that will change the web is a whole other story, but one that depends too much upon unknown particulars to go into at this juncture.

There is also the question of a continuous database of what you own: an electronic bookcase or locker. How will it be maintained? Who will have access to it? Nobody knows, but its existence is a no-brainer in a few years, because people will not like it if they can’t go back to articles they bought a year ago.

The important thing, at any rate, is that this simple pay structure gets established. Because that’s when real studies of consumer behavior on the web will take off. Our studies today are like the dirty backroom fumblings of 15th-century naturalists trying to determine the nature of light.

The important thing, at any rate, is that this simple pay structure gets established. Because that’s when real studies of consumer behavior on the web will take off. Our studies today are like the dirty backroom fumblings of 15th-century naturalists trying to determine the nature of light.

Hypothesis: People will pay for our content

Experiment: Make entire site pay-only for a month

Result: People didn’t pay for our content

Hypothesis rejected

That seriously is the level of rigor we’re applying to this problem. And it’s partially because, like those medieval forbears of our modern scientists, we don’t have the right tools. How are you going to study the habits of consumers when at the moment, consumers have to break every habit they have when taking part in online commerce? Our methods simply are inadequate.

So: once the tools are available, the big publishing companies (and of course, websites like this one) will experiment. Some will try to charge a small amount per article. But difficulties arise there as people don’t like paying so frequently, even trivial amounts. Then, maybe some charge for daily access. But people will find content they don’t like and complain that they could have paid for just the articles they wanted to on that other site. Yes, it’s ridiculous, but remember, people are ridiculous. Still others will try the monthly route, or even yearly, but what’s the right price? You can’t jack it up and down to counter movement in the market — subscribers will reject that kind of uncertainty. And even if you think your content is worth $20 a month, many consumers will opt for a cheaper subscription, even if it’s of lower quality. How to convince them?

Difficulties, difficulties! And unfortunately, I’m not a seer, so I can’t say where the prices and payment contracts will land, exactly. But I can say that the trick is to offer all of them, and make each one a valid value proposition, each one saving money over the other to the eyes of the consumer segment being targeted. The prices will be low, but not absurdly low. Nobody would buy an article for a penny. If I had to guess, I’d ballpark the figures thusly:

Single-article purchase: 10¢ – 50¢

Single-article purchase: 10¢ – 50¢

For popular columns, features that attract wide readership (columns by famous authors, etc), and exclusives. The price must be low enough that someone feels they’re only paying for the privilege of reading the original. Essentially, you’re selling the delta between what I write about an exclusive, and the exclusive itself. Of course, with longer articles and more affluent demographics, you can jack that up a bit; I’d gladly have paid $0.50 each for a lot of the best New Yorker-type articles I’ve read.

Daily pass: 50¢ – $1

In years to come, I suspect people will be loath to pay more than a dollar for an issue of almost anything. Sure, there will be exceptions, and sadly enough a dollar ain’t what it used to be, but the fact remains that it’s a dollar, and other online outlets (iTunes for instance) have popularized that price point as a simple and reasonable price for… almost anything. Today, you often pay far more than this for a paper, and magazines are of course absurdly expensive (printing ads gets expensive). The value proposition here is that it’s not much more than just buying an article, but when stacked, more expensive than (see below) a monthly purchase. It’s an easy sell since there’s lots of content, and you make it up on volume. This is the equivalent of the newspaper stands on the street — people who don’t subscribe pick one up when they feel like it, because it’s there and the price is right. Some outlets, like USA Today, will go for a lower price like 50¢ because… well, you know.

Monthly pass: $1 – $10

What, a monthly pass starting at $1? Crazy talk. No, actually, it’s not — but that sort of monthly pass, at the low end, is something that might be collected into a single yearly fee, or even a one-time entry fee, like Metafilter. More on this later. And despite some sites already attempting to price monthly subscriptions at far higher than $10, I wonder if $10 is still too much. It’s a decent ballpark, anyway, and it’s a great deal for the consumer. They save a ton, the content creators get guaranteed income. Additional perks at this level might be warranted; more on that later as well.

“Regular” news articles: Free

These will always be provided as “editor’s choice” or “front page,” since most publications want to bill themselves as being a reliable source for all kinds of information. This makes the paywall into more of a payfence.

A natural objection might be that this pricing scheme I’ve suggested will not provide enough income for a publication to function. At current readership levels, yes. But the fact is that there are going to be more ways to consume Wired or the New York Times than simply picking up a paid-for physical object or going to a free website. The reach of publications will be far greater, and their costs for distribution far less, and although there may be some stumbles and buyouts along the way, the old ink-and-paper media companies will metamorphose into something new, interesting, and successful.

And it goes without saying (yet here I am saying it — another unnecessary thing to say, which I am also saying, etc) that there will be exceptions. Premium content will of course be able to command premium prices, and there will be bargains, special deals, licensing issues, extra microtransactions within the paper, and so on. And, as I outlined a year ago in my article The Ad Supported World, rich content will make targeting and selling to your readers unbelievably easy and effective. If your reader only reads the sports and leisure sections, and buys daily, that says a lot about him as a consumer; right there you’ve narrowed down potential ads and purchases by 80%, and can charge considerably more for these more targeted ads. That’s part of the revolution in advertising that will take place — not to mention instant sponsored purchases of songs by highlighted artists playing in the city, or referral setups to buy tickets to the next showing of the movie you just read a review of, and so on. Indirect monetization will allow content providers to print money in a few years, if they’ll only commit.

But I digress. Let’s see what else the future holds.

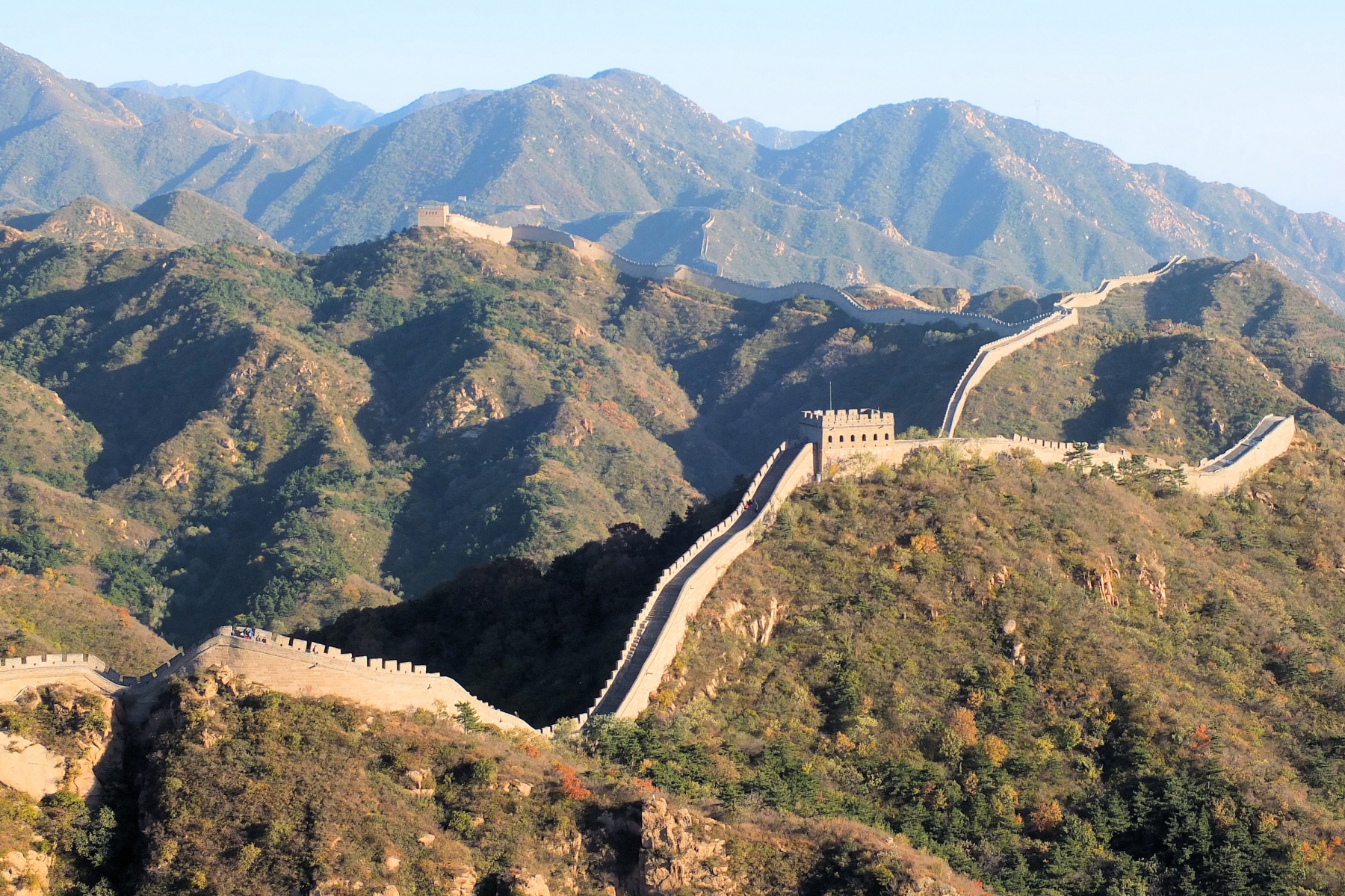

The Great Paywall Of… Yahoo

Image Credits: Keith Roper (opens in a new window) / Flickr (opens in a new window) under a CC BY 2.0 (opens in a new window) license.

It’s all well and good for me to imagine all these publications working these things out individually and promoting themselves with good content and fair prices. And a chicken in every pot, right? The truth is there are ruthless media companies for whom these publications are just marionettes, and things won’t be that easy. Fortunately, this is my article, and I’m going to skip over the part where the big media holdings companies stonewall progress and sink a few of their own ships in the process by insisting on DRM, outrageous pricing, premature launches, and plain bad content. That’ll happen, in fact is happening already, but that period of strife is uninteresting. We know where they’ll end up, just like how we knew in 2002 where the RIAA would end up. That entity is still kicking and streaming, of course, but these things take time. Rome wasn’t sacked in a day.

After the dust settles, I envision the paid internet as a sort of collection of walled towns, or city-states. Inside one, all the holdings of News Corp. In another, Warner. In another, Aol. Because the internet is about sharing, connectivity, cross-references, and of course the occasional backroom deal.

At first it will be between related sites owned by the same overlords. So in our case, just for the sake of illustration, a subscription to the TechCrunch network (a bargain at any price) will allow you to purchase a similar subscription to TMZ at a discounted price, or maybe you get a month for free. Simple stuff, right? And natural. It’s the kind of share-the-halo business strategy that’s been at work for years in tons of other contexts. So that’s a guarantee.

What I’m interested in, however, is more independent city-states. Ones anyone can move to — for a price. I haven’t fleshed this idea out completely in my head, but I think we’re going to see establishments arise that have no purpose other than to arbitrate access to a set of websites. Think of it this way: You pay amount X for access to sites A, B, and C, maybe a few non-corporate gaming sites or something (call it ABC). That amount is distributed among those sites. Why don’t they just become one site? Well, it’s not quite like you pays your money, you gets your site. The payment system and benefits would encompass these sites, but would be the limit of their affiliation.

But say site D wants to join in. They want to be part of the network. I think there will be a new business model (probably not new, actually, despite my thinking it up, just adapted) by which access to a readership is given in response for a buy-in amount. They would then share the earnings proportionate to how much traffic they drive, or how many new subscriptions, or maybe just a fixed rate. On the other hand, ABC might want to “acquire” site E for exclusivity behind their paywall, and will of course offer revenue sharing, promotions, and all kinds of other things.

It’s still pretty woolly, but I do think that a new class of payment arbitration business will show up once that kind of funding for a site becomes more common. After all, we have large ad networks managing and serving the ads on our sites, it’s only natural to outsource this kind of thing. These days, there are the modular, the vertically integrated, and the dead. If you’re not big enough to be vertically integrated, you better modularize.

And will the larger entities, like News Corp, allow for things like buy-ins? I think we may be surprised at what they’re capable once they abandon their outdated ideas of how traffic and income work, but that’s as much as I’m willing to commit to at this point. Anyway, if this portion of the article was unconvincing, just be glad I didn’t go with my original idea of an entire post extending the “city-state” metaphor to its breaking point.

Providing for your flock

Reader retention (and its equivalent with other types of media) will increase in importance as more of a site or network’s income is directly derived from readers. Indirect advertisement deals, like monthly rates for a certain-size banner ad, are going to nosedive, since they’re trivial to block or ignore and everyone hates them. As I said before, this change from indirect to direct income from readers is a change with great risks and great opportunities. There will be a reckoning a few years from now, when traditional advertisement returns are flagging, and only those suited for life in the harsh new climate will survive.

In addition to the things I suggested earlier in the article, there will be some serious content wars in order to differentiate coverage and provide flavor to a site or network. This will be complicated by the fact that almost any content can be copied by a subscriber and pasted to his or her personal blog, or torrented, or spread by any number of alternate means of distribution. The value, then, can’t simply lie in the content, but also in the container.

That’s pretty scary to me — I’ve always espoused the view that if you have good content, the people will come, and hopefully that will stay true to an extent (it will remain my philosophy regardless). I am, however, comforted by the fact that a truly convenient payment system combined with truly reasonable prices will obsolete casual piracy. Serious piracy and hacking will, of course, remain, but I seriously doubt it will be easier for an end user to pirate/sideload an exclusive article or video than to pay a quarter and have constant legal access to it. The law here (DMCA, COICA and beyond) will make a difference too, but in the end, I think people won’t mind parting with pocket change.

Community and discussion, too, may provide another carrot for consumers. I mentioned Metafilter; it’s one of my favorite sites because the paltry $5 entry fee is, for the carrion eaters and rank trolls of the internet, an insurmountable barrier, or rather one they don’t care to penetrate. The question is whether it will remain so when payments like that become more ubiquitous. I personally believe it will: only being able to comment or vote on articles you’ve paid for (as at Metafilter, you pay for all ahead of time) is a powerful filter, and it will make user input much more valuable and relevant to all concerned. When I see articles with four or five thousand comments on the Huffington Post or some mainstream news site, I sometimes feel physically ill from contemplating the signal to noise ratio therein.

Paying for something also means that you are being a part of something others pay for, and there are responsibilities that follow. Etiquette and standards will shift as money and exclusivity enter into the equation. “Excuse me, sir, but other people have paid for the privilege of using this site, too — so we’re banning you.” And I won’t lie, subscription and payment options are also ways for sites to gain a level of control over their users via EULAs. The balance of power between content providers and readers will be hotly contested, especially when it’s clear that the readers so directly fund the providers. But that’s one of those disputes that’s likely been going on for several centuries, and will continue for several more. Let’s pretend I didn’t mention it.

Caveat

The trouble with this great house of cards I’ve stuck together with anecdote, chewing gum, and speculation, is that when you step back and look at it, it just appears too complicated. That’s my main objection to my own theory here. It reminds me of the way TV is being diced up and served piecemeal to consumers online now. It takes a meta-service like Google TV to make the 10 different network sites and accounts palatable to the average consumer, and as we’ve seen, it’s not being welcomed by the powers that be, and even if it were, it’s not yet up to the task.

The overlapping nation-states of multi-site paywalls and microtransaction systems is going to be too much for the average webgoer — the hundreds of millions of people who google Facebook every time they want to log in, and who are still suspicious of Amazon, to say nothing of electronic wallets. I don’t mean to demean them (well, maybe a little), and it’s partially the fault of computers and the web being inaccessible for many that this population is so important. But as much as I’d like to think that in five years there won’t be people googling Facebook, I seriously doubt we’ll have advanced that far.

At the same time, I doubt there will be an “extended cable” style version of the internet that provides access to all or most paid content. And of course, there is the issue of net neutrality mixed in there, too. I’m going to just go ahead and say that I have no idea how it’s going to work, and I’m okay with that. There certainly will be systems and allegiances like those I’ve described, but there will be major differences as well, and those I can’t predict. I welcome your input, and remember, since the keys to this magical kingdom of paying customers are tools we don’t yet have, we’ve got plenty of time to think on it before it becomes reality.