Every generation thinks that they are the first. The first to feel this way or that, the first to make this or that revelation, the first to do and make things that we find later have been done and made since before we could record their doing and making. But while these illusory and fleeting firsts are common to every generation, there are true firsts being achieved constantly, though they are often subtle enough that they are not noticed even by those in their midst. My generation has been lucky enough to be part of a very important first.

The personal computer (in all its forms) has grown to be, I would say, the single greatest potential source of prosperity in history. It has enabled the internet and a consequent democratization of all sorts of arts and information, as well as the ongoing destabilization of financial institutions via distributed money transfers. The revolution, and it really is one, is ongoing. How unlike the world of 2000, of 1990, is the present day? And 2020 will be doubly, triply removed. As technology further enables itself, the positive feedback creates a greater rate of advance, and thus our acceleration; if this interests you, you should probably go talk to Mr. Kurzweil, since he’s done a bit more work on the idea. I’m not concerned with the singularity, however: my object is the generation to which I belong. I propose that this generation, which I am going to call Generation I for a number of reasons, is the only one to which the rate of advancement of technology was exactly fitted. At no other time in history, and perhaps never in the future, will there be a group of people whose own growth and maturation is so perfectly reflected in the principal technological and cultural advancement of the age.

It’s a serious claim, but I hope to show that it’s founded in observation and not egomania. And let me remark further before I begin, that I am not claiming any special merit for this generation, only a special situation. Lastly: I will speak of “advancement” or “progress” as if they were objectively measurable, when clearly there is much to be said on what those concepts actually consist of. But for the purposes of this article, let us consider them to be, say, the progressively sophisticated bending of the natural world to our needs and wants.

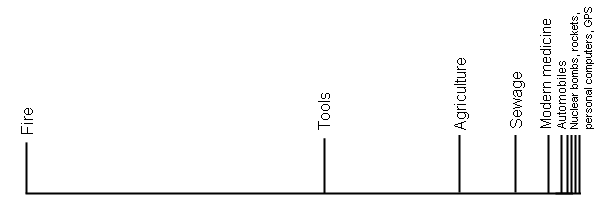

As even a casual student of history (read: a grade-schooler) can see, the rate of technological and cultural advancement has ever accelerated, of course with some interruptions due to warfare and subjugation. This is first observable in the length of “ages” — the stone age, 40,000 years. The bronze age, 2000 years. The iron age, 1000 years. There are too many books written on this topic for me to spend many words on this, and at any rate this acceleration is palpable to those of us living in the modern first world. Moore’s Law was once a simple prediction; now it’s practically a force of nature.

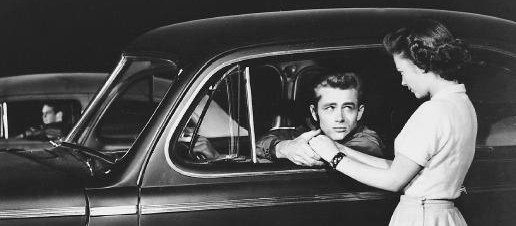

Let us look at recent history, to prime our minds for the idea of what I would call a “generational technology.” The car is a perfect example. Prototyped in the late 19th century, manufactured widely in 1915, increasingly affordable and common over the next 30 years, then producing a “car culture” in the 50s and 60s, followed by an increasingly consumerized nature as the automobile was integrated completely into civilization, and cities and lives began to be designed around it. Today the integration is complete, and perhaps we are on the verge of another change, to a post-car world. I don’t know. But the divisions in the car’s history, you see, are a lot like generational periods. The specific dates and years aren’t important, as generations are a sort of rolling concept, and the lines are wherever the historian finds them convenient to be. So let us look at the stages of the car, which I have also given names (I’m a coining machine today):

Hammer stage: During this time, the concept and platform of the automobile were being determined by the founders and inventors. Things like setting down how many wheels a car will have, which method of propulsion it will use, the materials it will be built from, and so on. There was surely some bickering here, as there was between AC and DC when prototyping electrical devices, but one fundamental form is almost always selected, and for the car it was four wheels, front engine, and internal combustion. This stage is performed entirely by an older generation of inventors, investors, and engineers.

Paper stage: This is the period where the creators turned the design over to the marketers, who make it into a product. Extra features were created within the confines of the pre-established framework, manufacturing methods were improved, the whole process made faster, and other steps taken to make the technology affordable and attractive. For the car this was of course improvement in reliability, luxury, and speed, among other things. It is a stage of intense competition among marketers, who must both inform and sell to the public, to whom the idea of the car (in, say, 1925-1940) is still new and barely affordable. They are largely ignorant on the subject and are likely skeptical.

Tinker stage: Once the car was adopted by consumers at large, as cars were by the close of World War II, the next (very numerous) generation grew up with the “new” technology taken — I don’t want to say for granted but perhaps as granted. The car culture of the 50s and 60s was a result of a generation of people in tune with an important and exciting technology, a generation as familiar with the car as they were with the clock. There was an expansion of the purposes of the car during this time, as well as a great improvement in their quality, since this generation, having grown up with cars, would work to provide the advancements that were not possible under the auspices of either their parents or the inventors, whose ideas were likely no longer applicable. This positive feedback loop, as in other technologies, leads to a second push and prepares the way for the fourth stage.

Mirror stage: Once the car had been proposed, adopted, and grown up alongside of, in the three previous ages respectively, it was ready to become fully integrated. Not just because it had gotten to a certain level of affordability or reliability, but because it was an integral part of the modern person’s life already, and now the task was to shape civilization around it. While the highway creation act in 1956 obviously wasn’t driven by 10-year-old baby boomers, the obligation of government and industry to acknowledge the growing importance of the automobile was clear enough once it was recognized at large as foundational. In this stage nearly everyone is part of the process; the automobile has impressed itself on civilization, and civilization must now reflect it more fundamentally. The term Mirror Stage is actually an existing psychological one (as well as an excellent game), and refers to the period at which a child becomes captivated with its own image. I thought it loosely appropriate.

Essentially: invention, introduction, internalization, integration.

But is there another stage? I don’t think so. The cycle is complete: the changing world births a new technology, the technology is popularized, refined, and eventually fuels the next change. I chose the car as a representative because it is familiar and its effects clear, but with a little work I think that the model I’ve just suggested can be applied to pretty much any technology, from aqueducts to longbows. But this isn’t a longbow blog — so let’s move on.

Note that, in the example of the car, each stage is relegated roughly to a generation. The inventing generation sells to the adopting generation, which brings up the integrative generation. Furthermore, the inventing generation cannot be the adopting generation, and the rate of progression in this case prohibited the adopting generation from being the integrative generation; for the car it took around 50 or 60 years, arguably more, for it to reach its Mirror stage. My belief is that Generation I (born roughly between 1975 and 1985) is the first generation, and possibly the last, to see and be a part of every stage: to be a part of the genesis, popularization, refinement, and counter-refinement of their age’s defining technology.

Now, I don’t claim we invented the personal computer; nor, I’m sure, would those who are cited as having invented it. Like the automobile, the computer was a long time coming and was enabled by advances in many other technologies and disciplines. Early computing was as an exercise in logic, mathematics, and electrical engineering, and its early advances academic. What defined the automobile, and what has defined both the computer and the age in which it has proliferated, was not in fact the creators (brilliant though they were), who were the implements of history, but the people who used them and guided their use. For the car, that definition was stretched out over long decades, and people grew old while automobile technology remained young. For the personal computer and the internet, the infancy of the technology coincided with the infancy of my generation, its adolescence with our adolescence, its growth with our growth, in such a pas-de-deux as has no precedent in history and, for all we know, may have no equal in futurity.

Generation I is the middle child of the information age. To be born a few years earlier would mean to see the personal computer and the internet as an new and exciting gadget, like the VCR or Walkman. A few years later would be to arrive late to the show: to grow up in the presence of computers, smartphones, and the internet, but not to grow up with them. Taken for granted, these things become black boxes; on the other hand, seen as just another set of devices and applications, they lose their transformational potential. I think the timing is very important, but of course as part of the generation, I am prone to that error.

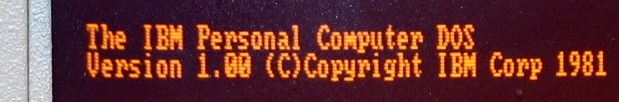

Our readers will probably remember that computers around 1980 were ugly, limited, and expensive machines. They performed a few of the functions we still value today (word processing, calculating, games) but had no GUI and little connectivity. I don’t want to overstate the parallels, but just for clarity in what I am driving at, consider that an apt comparison might be to a young child, able to see and crawl, or walk totteringly — fundamentally intact, you see, but encumbered with limitations that can only be changed with time and effort.

I remember learning just enough of my dad’s old work computer to find tic-tac-toe and play it on the flickering amber screen. A few years later, primitive UIs are emerging, so primitive that the command line is still unarguably the more powerful tool. Just as Generation I begins to learn to read and to speak, the PC can be communicated to in what we understood as plain language. The first truly popular computers proliferate, running DOS, and a few of us were lucky enough to play with one of the later Apple II models.

In 1990 the GUI and the more complex tools it enables begin to flourish and become fundamental to the PC experience, as Windows 3.0 and the Mac Classic hit the market. Shortly after that, the first affordable modems. BBSes, AOL and its chatrooms and fake internet, and then the revelation of the true web with Mosaic, Internet Explorer, and so on. I won’t waste your time with further details you’re almost certainly familiar with (having lived through them), but you must see the way things are not moving at the rate of a stage per generation like the car. No – they moved more quickly, but not so quick that we lost track. This particular speed of maturation (from “infancy” to “adulthood,” which we may define as, say, Windows XP or OS X; after that I believe the core functionality of the PC OS has not been substantially altered), which is roughly the same as the speed of maturation for a human being, and Generation I has the privilege of being the computer’s twin sibling, if you will.

Though the virtue of being born at the right time is not ours to claim, nor is it simply a novelty that Generation I has grown up in tandem with a world-defining technology. As we grew up with it, we have seen and participated in all the stages of generational technology. We witnessed as children the squabbling between Atari, Microsoft, Amiga, and all the others as they beat the raw metal of computing technology into a shape the world could use. We knew it when it was young, and then we helped it become a household technology by simply being in the household, the way baby boomer kids grew up around cars and ended up knowing cars better than any generation before them. However, cars as a technology practically stood still for the car kids’ formative stages. Not so for us: every year the computer was changing its case, its OS, its capabilities, its interface — everything changed about it, but we still recognized it, the way we’d recognize an old playmate year after year who, though changing in size, aspect, and ability, we still know. That is how Generation I knows the computer, the internet, the smartphone, and whatever comes next. Not as a series of devices, but as the natural progression of a friend whom we know by sight in spite of the changes wrought by time and culture. Perhaps it is best expressed that we know the ghost in the machine, that which has informed and guided the progression of the technology from household appliance to a tool as fundamental as the wheel.

Captain Nemo took pride in the Nautilus “moving through a medium of movement.” He meant the ocean, of course, a place that is never the same one instant to the next, but which he nonetheless knew and navigated freely because… well, because he had a submarine. The metaphor doesn’t extend that far. But the idea of moving in a moving medium is a powerful one. To truly understand the way that the world changes around you, and to not only be able to survive in it but to thrive, to navigate, to direct that change, that is the privilege of a generation born into movement.

I see in my flight of fancy I’ve built up Generation I into quite a ridiculously grand thing, and in doing so made the same mistake that I described in the first sentence of this article. I did not mean to do so, but the simple boon of being born alongside a world-changing technology is not minor: it matured with us and has shaped us as much as we have shaped it, and that means that we are on the front line for the Mirror Stage of the information age. Can you forgive me for being excited to be a part of a sea change in civilization, a change in infrastructure perhaps more fundamental than the integration of the automobile? Few events in history are the equal of this impending shift, if I’m not mistaken. I of course don’t claim it for myself or my generation; it is a glory we will share in, but which we may be able to uniquely enjoy. Imagine being the childhood friend of the first man to set foot on Mars. It’s no credit on yourself exactly, but you just may understand him more fundamentally than anybody else.

What’s that I hear you saying? That we haven’t actually contributed much to the progress of the personal computer and the internet? Very true! If I’ve claimed otherwise I’m very sorry, because Generation I, like the baby boomer generation in the 60s, isn’t quite ready to make our mark. The fact is we’re just starting out. What was the work of the baby boomers? Was it driving cars around fast and knowing how to clean a carburetor? Hell no. Their task wasn’t just to know the technology that would shape their world, but to shape their world. And that’s our job as well. What changes the world will know in the next 20 years are impossible to predict, but you better believe that Generation I are going to set their shoulders to it. The Mirror Stage awaits.

And why Generation I? Before us is Generation X, or so we are told. I’ve heard people my age, or my brother’s, called Generation Y. It’s no use naming a generation before their purpose is clear; otherwise the Greatest Generation would be called the Kaiser Kids or something horribly inappropriate. Generation I occurred to me as I was writing this piece, and as far as I can tell it’s the most evocative of that which truly defines us.

Generation I reflects the burst of technology which in the last decade (as we ourselves have made our real-world debut), has become commonplace, and the prefix “i-” has become a universal indicator of tech. Yes, it’s a bit of a capitulation to Apple, but let’s not fool ourselves: the iPod and iMac immediately became so synonymous with personal technology that i- became generic almost overnight. So we’ve got Generation i. To be honest, I’m not sure if I prefer i or I. I think that, like other instances of the letter, capitalization may vary.

Generation I is also Generation Me, signalizing the increasing independence and compartmentalization of the social order that is the result of the personal computer and the internet, our totem technologies. It’s the paradox of instant connection and constant isolation.

And Generation I is Generation One. This is the most important of all. The coincidence of timing that resulted in us being born with silicon in our mouths also charges us with a serious responsibility — though what it may be is yet unknown. No generation is warned of the tribulations ahead, though with luck our task will be suited to our unique position. But why the One? If, as I suspect, we are in fact the first wave of a new, tech-integrative sort of people, then surely the kids born after us, into a world already possessing high-speed internet, Wikipedia, and GPS smartphones, are Generation II. What better than to start giving version numbers to our offspring? Seems like something Generation I would do.

I’d like to conclude with an apology. If you’ve read this far, there’s a good chance you’re seething with anger at having been excluded from what I seem to think is the most awesome generation of all time, who invented everything worthwhile and will do everything important in the future. I want to correct that potential misconception, though I understand where it’s coming from. Obviously the pioneers of the information age are largely baby boomers, and of course Generation X is one of the great utilizers of technology. And for that matter, kids today fulfill many of the conditions that I think make Generation I so special. I can only say that I tend to get carried away, and that our special situation is really the main thing we have going for us. Am I reaching? Very likely. Am I romanticizing? Most certainly. Let’s chalk it up to youthful vigor.

It is probably true that every distinct generation is born into a confluence of circumstances that is consequential in its own way. Too often, though, I have felt that people my age have been maligned as a passive generation, one of consumption and luxury. That’s actually true as far as it goes, but there is much beneath the surface; who would have thought that the boomers, flower children and hot-rodders in the 60s, would be galvanized by the civil rights movement and Vietnam, emerging to become the most powerful demographic in the country, and perhaps the world, for decades running? It is toward such heights that Generation I must drive itself. We must show ourselves equal to the special favor we have been granted, and do our part to carry the world into the next age, whatever it asks of us.

Note: if you comment about how this article was too long for you to read, your comment will be deleted. Who cares?