Like most things on the Internet, there’s a good side and a dark side to where the media business is headed.

Like most things on the Internet, there’s a good side and a dark side to where the media business is headed.

The good side is very good: thousands of layers of mostly needless middlemen and processes are being eliminated as journalists get a direct channel to their readers. And, because it’s a two way medium, readers get that channel right back. And in the cases where the subject of an article has been wronged, the Web gives them powerful megaphones to fight back. In short, the more everyone has a voice, the more reporters are challenged to make sure they are right, because they will be called out.

Look at what happened with the plagiarism scandal around Chris Anderson’s new book. Anderson says it was a mistake around a change in how they were going to use citations, and I take him at his word. But it’s safe to say any author who’d considered borrowing heavily from Wikipedia won’t now. We like to think that we act virtuously because of personal or professional pride, but nothing enforces those ethics like the real possibility of getting caught and hugely embarrassed.

But the bad side is also very bad. The elimination of those layers – typically fact checkers, editors, lawyers and just time to make sure a work is fully baked—also allows mistakes, lazy reporting, a dependence on rumors, and hot-headed, unfair treatment to subjects. Worse: The metrics around the Web make it crystal clear which kinds of stories drive the most traffic. That leads to salacious reporting for the sake of clicks and comments.

It’s easy to point the finger at blogs, especially by certain members of old media losing money quarter-after-quarter. (Cough, cough.) But this is not just a technology change as most corners of media are fighting for survival, it’s become a cultural change. And this week, I’ve been struck by two non-blog examples that reflect the tension.

Right about now most people reading this probably have guessed the example of salacious reporting and unfair treatment I’m driving at is Ben Mezrich’s new book on Facebook. I’ll say upfront I haven’t read it. Galleys have been very closely guarded. Once I do read it, if everything everyone who has read it has told me is wrong, I’ll apologize for what I’m about to say. But, on a professional level, I find the ethics behind this project disgusting.

It’s essentially a book based on talking to one source who had a falling out with the company just as it was moving to California and becoming more than a dorm room project. That’s like someone writing a book about you based solely on what your old college ex-girlfriend or ex-boyfriend said.

Mezrich has been clear to say he’s never met or talked to Mark Zuckerberg in the intro and in interviews, but that doesn’t stop him from drawing potentially damaging conclusions about his character and selling it as a non-fiction book that’s getting made into a movie that people will take as fact.

In contrast, I spent years and hundreds of hours interviewing and following the subjects of my last book, which as most people know, included Zuckerberg amid other Web 2.0 figures. And I’m about one-third of the way through research for my next book, which includes spending 40 weeks in other countries following entrepreneurs. It’d be a lot easier to write a narrative without that whole burden of actual reporting. If I could sit in Silicon Valley and make up what I think entrepreneurs in Africa are like, that’d sure help out on my bank account, my health and my neglected personal relationships.

To be clear, I have no doubt Mezrich’s book will sell better than mine and make a juicier movie. But I wouldn’t swap the karma points. I don’t know how you call yourself a non-fiction writer and publish a book about a living person that’s based on you “imagining” what they are like. And let me tell you, having first interviewed him when he was 19 and spent countless hours with him since, the idea that Zuckerberg is some kind of sexed-up lethario is laughable fiction.

Why didn’t Mezrich write a novel or a different non-fiction book that he actually knew something about? It just seems like a cheap way to get a film deal and sales since the “imagined” subject is also leading the hottest private tech company in the world right now. (Indeed, the film rights were reportedly sold before the book was written.)

Even Mezrich’s publicist admits as much, according to a New York Times Blog post where he said, “The book isn’t reportage. It’s big juicy fun.” I’m guessing it’s not fun for the people trying to build a company who Mezrich essentially calls womanizers, drug addicts and backstabbers. Probably not fun for their families, employees and investors either. If this is where media is going on a book level, magazine level or blog level—I want out.

Contrast that to what’s playing out with another hot non-fiction book that was also optioned for a film: Moneyball. Some people accuse Michael Lewis of taking some liberties with facts here or there, but I’ve never met one of his subjects who felt he was treated unfairly, including the subject of Moneyball, Billy Beane. Like his style or not, Lewis did his job: He invested countless hours reporting and wrote a book that told a dramatic story that also happened to be true.

Recently, that book was also being made into a movie, to star Brad Pitt and be directed by Steven Soderbergh. The plug unexpectedly got pulled. It seemed Soderbergh reworked the script to be less a feature film version of things and more a real-life reenactment with some of the actual people playing themselves. Quippy anecdotes and funny lines were cut because they weren’t actually said in real life.

I’ve not been a huge fan of some of Soderbergh’s more experimental work, and I don’t know if his treatment would have made a better movie. But imagine: The people who are allowed to take the most liberties with a “true story”—the filmmakers—hewing more to the truth than an author who ostensibly gets paid to write the truth.

The media world is upside down these days, and I hope when all the volatility is done we wind up on the Soderbergh side of things.

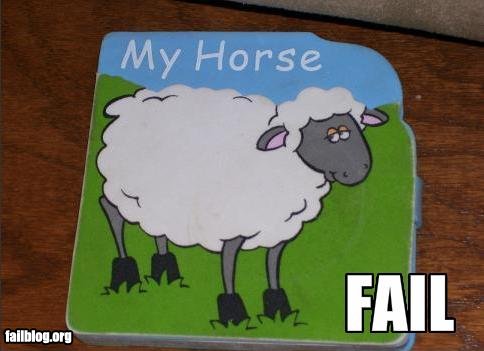

Image by failblog.org