Food is the very nourishment of life, but it’s also becoming increasingly challenging to grow at scale. A combination of explosive and unsustainable population growth, human-made climate change and depleted sources of clean water is contributing to overcultivation across the world.

For its many advocates, vertical farming is a critical piece to solving that puzzle, even as skeptics cite its intensive power demands as a major hurdle toward achieving the long-term positive climate impact it promises.

Existential crises of climate change and substantial food shortages have fueled interest in alternative forms of food production, while innovations in technology have created the potential for delivering those ideas at scale.

The pursuit of sustainability was a key catalyst in the formation of Bowery Farming — and, for that matter, the development of vertical farming as a whole. Global climate disasters have spurred companies and governments to increasingly explore large-scale solutions, and that’s why increasingly bullish investors are pumping money into the space — the company raised a $300 million round this May.

Companies like Bowery have captured the imagination of the public for the role they might eventually play in helping reshape the 10,000-year-old practice of agriculture. It’s big talk, but it’s unsurprising in a world inexorably drawn to the notion that the solution to righting the wrongs of decades of harmful technologies can be found in technology itself. It’s a hopeful thought.

In the first part of this TC-1, I will look at the origins of Bowery Farming as well as the vertical farming movement as a whole. I’ll also discuss how Japan’s 2011 tragic earthquake catalyzed interest in the model and also explore how these new approaches to agriculture could usher in critical changes on an Earth with rapidly changing climates.

We’re not in Kansas anymore

The best way to understand a farm is to visit it, so I set up a tour to see what Bowery is building. I intend to arrive early, making some vague plans to walk to a nearby coffee shop, set up camp with caffeine and Wi-Fi, and prep for the day. As we approached the destination, however, that plan is quickly scrapped.

As the crow flies, Bowery Farming’s Kearny, New Jersey R&D center is roughly five miles from Manhattan, but the surrounding neighborhood contains none of the trappings of bustling city life. Just industrial warehouses and little else as far as the eye can see.

The first stop on the itinerary is Farm Zero, an active vertical farm and research facility. My Uber driver pulls around the rear of the building, flanked by semi trucks loaded into docks.

Some days, this gig flies you around the world to Nigeria or Tokyo, and some days, you find yourself in a New Jersey warehouse loading zone at 8:30 a.m on an unseasonably rainy Thursday in early September.

A week after Hurricane Ida sowed chaos up and down the Eastern seaboard, though, perhaps there’s no such thing as “unseasonable” anymore. The immediate impact of climate change is top of mind as I look for the entrance in the gloom of the loading docks. Indeed, for the rest of the day, we never stray too far from the subject.

The pastoral depiction of the farm, updated for the 21st urban century. Image Credits: Brian Heater

Entering the building, you pass through a small space — more doctor’s waiting room than proper lobby. It’s standard fare for startups like this: A holding zone with couches, a coffee table and an attached kitchen. This waiting room, my first tour guide, chief science officer Henry Sztul notes, is where things started in earnest for the company six years ago.

The earliest experimentation with indoor growing that would give rise to the firm — currently valued at $2.3 billion — started in this unassuming warehouse.

A TV mounted on a wall displays plant videos on a loop. The screen is divided into squares of produce sitting in their hydroponic cubes. Known as “Crop it Like it’s Hot” internally, the plants are static on screen — you’re actually watching lettuce grow in real time.

It doesn’t make for compelling viewing, as far as these things go, but a member of the team excitedly describes how a QR code could be printed on the back of a package of lettuce. Scanning it would bring you to a page displaying the specific growing conditions for that produce — the temperature, the humidity, when it was packaged and shipped, and maybe even a recording like the video we’re watching now.

There’s no shortage of ideas kicking around Bowery, to make no mention of the sheer volume of data the company collects for every head of lettuce it grows. When I mention the idea to Sztul, he happily expands on it — perhaps conditions could be tracked outside the farm, letting you know if someone at the grocery store left your produce sitting outside the refrigerator section for too long.

An early photo of Bowery Farming Chief Science Officer Henry Sztul building out the company’s early grow scaffolding. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

It’s a nearly absurd level of detail for a box of romaine, perhaps, but it’s within the realm of possibility for Bowery’s microclimate systems. In an age when we’re bombarded with more information than we can process, why not give people access to that sort of information about their heads of lettuce?

Not everyone in the world wants to read the hero’s journey of their arugula, but some surely do. Given that heads of lettuce are routinely recalled for E. coli and salmonella, that level of traceability may be something of a superpower.

Vertical farming takes root

While there’s an admittedly imaginative sci-fi element to much of this, what’s most remarkable about vertical farming is the speed with which it has grown from a seedling of an idea into an international industry.

Bowery’s story began in 2015, but the roots of modern vertical farming don’t stretch back much farther. While the term dates back a little more than a century, the original vision is dramatically different from the one we see today.

In his 1915 book, “Vertical Farming,” American geologist Gilbert Ellis Bailey describes a method for reaching nutrient-rich subsoil with the use of explosives — a rather hot topic a year after the assassination of an archduke kicked off the First World War.

The title page of the 1915 book Vertical Farming. Image Credits: Public domain via Internet Archive

“A world of wealth in thought, money, invention and machinery has been bestowed upon the first few inches of the soil at the surface, but up-to-date agriculture demands that the depths of the soil be considered also,” Ellis Bailey writes. “It is not enough to just scratch the surface and leave untouched the storehouse of wealth below.”

Exploding the earth remained the domain of military planners rather than farmers, but key enabling technologies were being invented throughout the 20th century that would make the vertical farm far more feasible.

Those developments caught the attention of Dickson Despommier, a professor of public and environmental health at Columbia who spent his career studying cellular and molecular parasitism. While teaching a course in 1999, he started thinking about what farming would look like in tall buildings.

“The idea actually arose among students who were concerned about whether they should go on and finish their schooling,” Despommier told TechCrunch. “These are graduate students that wanted to go into medicine, dentistry, public health … and they’ve actually second-thought the whole thing and said, ‘What the hell am I doing this for when there’s not going to be anything waiting for me?'”

Dickson Despommier of Columbia University and author of “The Vertical Farm.” Image Credits: Dickson Despommier

The small class pinpointed food concerns as a major driver of their apocalyptic concerns, from overpopulation to the ecological impacts of overcultivation and deforestation. The professor tasked his seven students with “short-circuiting” farming to determine whether enough produce could be grown on Manhattan’s rooftops to feed its expanding population. The numbers the class crunched came up almost comically short, meeting roughly 2% of Manhattanites’ caloric needs.

In the home of the skyscraper, however, another intriguing possibility presented itself: Rooftop real estate is a fleetingly rare commodity in a vertically oriented metropolis like New York City, so why not move the farming into the buildings themselves, eliminating the confines of seasonality in the process?

The ideas would culminate in Despommier’s book, “The Vertical Farm,” which was published almost exactly a century after Ellis Bailey’s similarly titled work. Despommier offered an equally hopeful, yet dramatically different definition of the concept.

“These farms would raise food without soil in specially constructed buildings,” he writes in the book. “When farms are successfully moved to cities, we can convert significant amounts of farmland back into whatever ecosystem was there originally, simply by leaving it alone.”

The book ushered in the modern concept of vertical farming, painting a vision of a future in which the world’s produce is grown in massive skyscrapers where its growers and consumers live and work. Think of it as a massive green food co-op.

The skyscraper scale is, for now, impractical (though entrepreneurs in places like Dubai certainly have it in their sights), but the definition has largely remained the same: Grow crops indoors in vertically stacked configurations designed to concentrate resources and reduce land use.

“To most who hear about this scheme for the first time, it all sounds too simplistic to actually have any chance of working,” Despommier writes. “It sounds downright naïve and impractical.”

Cover of “The Vertical Farm: 10th anniversary edition.” Image Credits: Picador

In the first edition of the book, published in 2010, he writes: “Although there are at present no examples of vertical farms, we know how to proceed — we can apply hydroponic and aeroponic farming methodologies in a multistory building and create the world’s first vertical farms.” A 10th anniversary edition published last year bookends the story with a 10th chapter titled, “And Then What Happened?”

A lot, it turns out.

The chapter offers a four-and-a-half-page list of “Select Vertical Farms,” opening with Bowery and its chief competitor, AeroFarms, which operates its own facilities a stone’s throw away in Newark. The list merely scratches the surface of the scope of the current efforts in the space.

The sun rises on vertical farming

Champions of vertical farming were once hard to find in the United States — after all, farmland is not exactly scarce here. But a generation of champions would be found all the way across the world among the lithe islands of Japan.

A year after “The Vertical Farm” was published, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the northeast coast of Japan. Tsunami waves over 40 feet high overtook the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Ōkuma, causing one of the worst meltdowns in history and contaminating vast swaths of the area’s rich farmlands.

“In the beginning people reacted to our product as something unnatural — machine-like — but by continuing to sell in the supermarkets people started to realize slowly that the taste was good and there were health benefits, so we slowly gained customers,” Shinji Inada, the CEO of Japanese vertical farming company Spread, told CNN in 2016.

“The turning point was the incident in 2011 at the Fukushima nuclear facility. After what happened there, people became more aware of the importance of safe food and it kind of turned the tables for us.”

Tsunami waves on March 11, 2011 smashed into much of northwest Japan, such as here in Fukushima prefecture. Image Credits: SADATSUGU TOMIZAWA/AFP / Getty Images

Japan is now home to more than 200 vertical farms. Most are small in scale and have struggled to hit profitability amid labor and energy costs. Spread, the country’s largest vertical farming operation, reached profitability after six years of production. “We started large-scale production in 2007 and finally in 2013 our plant became profitable,” Inada told The Financial Times last year. “We may be the only example of profitability for a large-scale vertical farm. Now we have the possibility of widespread market growth.”

Vertical farming has also been a boon in a country with an aging population, where the average age of a Japanese farmer is 67 years old — roughly a decade older than their U.S. counterparts.

Vertically integrated food production

The catalyst that pushed Japan to aggressively embrace vertical farming was a dramatic one, but the hope among technologists is that it won’t take a series of similar catastrophes to dramatically rethink the world’s approach to agriculture. Japan’s earthquake was geological in origin, but it’s not hard to imagine similar motivations when half the United States is on fire and the other half is grappling with increasingly intense hurricanes and flooding.

“Our current food system is part of the problem. Today’s agricultural supply chain, from farm to fork, accounts for around 27% of greenhouse gas emissions,” UN Secretary-General’s special envoy, Agnes Kalibata, wrote last year. “The food systems of today must change to achieve the ambitious goals and targets we have set for ourselves in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This transformation will require an unprecedented degree of cooperation if we are to succeed.”

According to a study published in Nature, food systems are currently responsible for around one-third of global carbon emissions. With the world’s population expected to reach 9.74 billion by the year 2050, we face an existential challenge: Will it be possible to expand food production while reducing its overall impact on climate? Failing to do the latter would serve to further exacerbate issues with the former, from flooding and drought to wildfires and further desertification.

It’s an overwhelming and seemingly insurmountable task — one that will require embracing emerging technologies and likely others not yet developed, married with more traditional sustainable methods of food cultivation.

While champions of new technology lean toward hyperbole when discussing these solutions, none that I’ve spoken with (Despommier included) appear to envision the vertical farm as a catch-all solution to the world’s climate problems.

Heck, livestock alone accounts for an estimated 14.5% of human-contributed greenhouse gases. But vertical farming’s proponents believe the technology could be part of a comprehensive solution.

Buffalo wings for lunch

Bowery’s founder wants to tackle these global challenges head-on. A veteran of Citibank and part of the early team at iHeartMedia, Irving Fain co-founded loyalty and marketing startup CrowdTwist in 2009. He left in 2014, around the time the company raised a $9 million Series B (Oracle acquired it five years later in 2019 for what Fain said was more than $100 million).

Bowery Farming CEO and founder Irving Fain. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

For his next act, however, he wanted to do something different. “I knew I wanted to apply technology to a category that had a deeper mission and meaning, and that’s what ultimately drew me to agriculture and specifically produce,” he said. He had grown up in Providence, Rhode Island, sitting at the alimentary crossroads of the state’s farming and fisheries industries, but he had a lot of catching up to do. “I read voraciously, watched everything I could get my hands on and talked to anybody I could talk to.”

After exploring drones, satellite imagery and enterprise approaches, he found himself drawn to urban solutions. That decision was driven in part by statistics: Roughly 83% of the U.S. population lives in urban areas. That number, up from 64% in 1950, is expected to increase to 89% by the year 2050.

Furthermore, a frequently cited 2003 study by Iowa State researchers determined that in Midwestern cities like Chicago, food produce travels an average of 1,494 miles from farm to table. Here on the East Coast, where much of our produce section relies on the nutrient-rich soils of central California, that number is often bigger.

Like Despommier’s students at Columbia 15 years earlier, Fain wondered what technology could do to help reduce the distance food travels.

Given the increasing popularity of “The Vertical Farm,” Fain scheduled a meeting with Despommier. The two wound up at an Irish pub down the street from Columbia in 2015, discussing the potential of the nascent industry. “I think every industry needs a north star at some point,” Fain tells TechCrunch. “I think Dickson has been a phenomenal north star of the industry, in some ways long before everybody was sort of onboard and believing in indoor farming. Do I think everything he imagines will come to pass? Not necessarily, but that’s not actually the goal of a north star anyway.”

Bowery Farming CEO and founder Irving Fain, seen here building out Bowery’s early grow scaffolding. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

He’s quick to position himself as a pragmatist on the subject of vertical farming, in contrast to Despommier’s idealism, which paints a picture of massively scaled food co-ops in a kind of urban-agrarian technological socialism.

It’s a wonderful vision, to be sure, and a version of this has the potential to take hold in countries like China, where the government is taking an aggressive interest in the technology. Here in the States, however, the success of vertical farming will almost certainly hinge on more capitalistic concerns fueled by VC investment and competing market forces.

Over a lunch of buffalo wings, Despommier asked the entrepreneur where he saw the industry in five to 10 years. Fain described a produce section where vertical farming companies were available alongside traditionally farmed options. Fain adds, “The focus has to become how do you both innovate and expand indoor farming, and how do you also, at the same time, make outdoor farming more efficient and more sustainable as well. Both of those practices are important.”

From lab table to farm

Like any new category, vertical farming is the product of the many breakthroughs that preceded it, beginning with the advent of modern greenhouses, which date back to the 17th century. Hydroponics, which allows plants to grow without traditional soil, became popular in the middle of the 20th century.

Decades later, the model was embraced by NASA as part of its research into controlled ecological life-support systems, which are designed to sustain life during space travel. By 1988, NASA plant physiologist Ray Wheeler had developed an early precursor to modern vertical farming that utilized hydroponics to grow potatoes.

“With potatoes, it was a little bit more interesting in the sense that you can’t use systems that require a lot of standing or deep water — potatoes don’t like to be submerged,” Wheeler said in an interview with the agency, “and we kept the nutrient water film very thin.”

These disparate threads of research and experimentation coalesced in the past two decades. Existential crises of climate change and substantial food shortages have fueled interest in alternative forms of food production, while innovations in technology have created the potential for delivering those ideas at scale. Success in vertical farming requires the correct combination of both.

Bowery’s earliest days were spent tinkering with technologies in an effort to validate these ideas. “This sounds like a zany science experiment, right?” Fain says of Bowery’s beginnings. “I personally didn’t feel like I wanted someone to finance my science project. I felt like it was sort of incumbent on me and the team to get as far as we could in validating whether or not this actually could work. So we did that and we looked … across greenhouses and aeroponics and aquaponics and all different hydroponic setups to land on the approach and the technology we’ve built.”

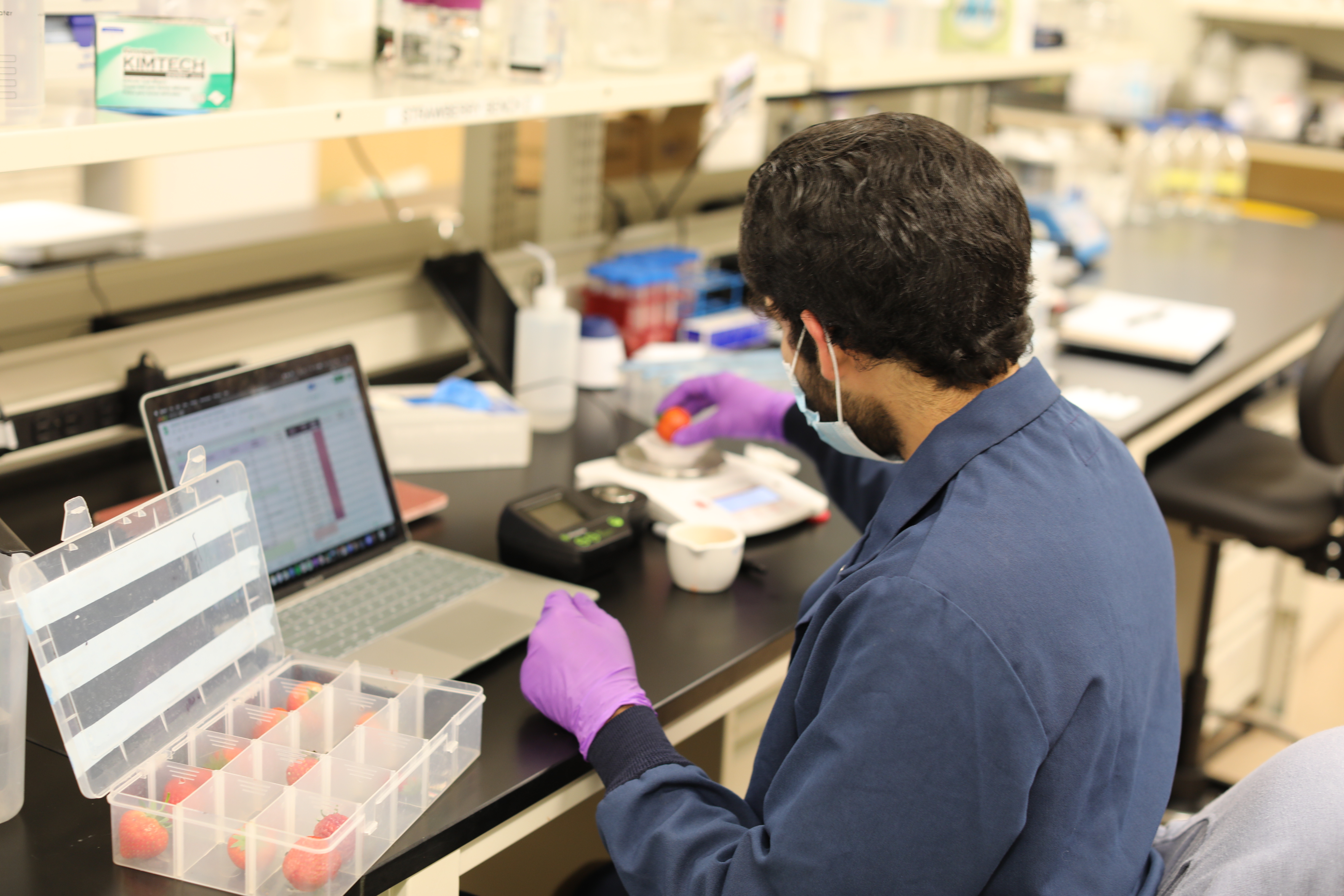

A scientist at Bowery Farming analyzes produce. Image Credits: Brian Heater

Entering the field as Bowery did six years ago entailed a certain level of jury-rigging systems together using goods purchased at hardware and grow supply stores in hopes of developing a method that could truly scale. Indoor farming has a history spanning decades, but there’s still a limit to what one can purchase ready-made for the nascent field of vertical farming.

When Sztul, the company’s chief science officer, left his job as a senior manager at Samsung to join the young company in 2015, Bowery was still in the throes of experimentation in the front room that now serves as the Farm Zero lobby.

Indoor grow supplies were available, but the nature and scale at which the team wanted to grow weren’t. “We started doing science from the beginning, because we always knew that there were better ways to do things, different ways to do things,” Sztul explains.

The Bowery, whiskey neat, grateful, I’m so grateful

The company adopted the name Bowery as an homage to its New York City roots. Now closely associated with an historically impoverished neighborhood and street in Manhattan, the term comes from “bouwerie,” an old Dutch word referring to the wide swaths of farmland that occupied the space in the 17th century.

More than two years after its founding, Bowery felt it had taken its R&D efforts as far as it could go with existing resources. The company raised a $7.5 million seed round, led by First Round Capital in 2017.

“With all the technological advances we’ve seen in the last decade, it is now possible to have reliable, consistent production in agriculture,” Fain told TechCrunch at the time.

Along the way, the company also found a surprise fan/investor in the form of celebrity chef, Tom Colicchio, who co-founded Gramercy Tavern in New York City. It was a big, early win, as hydroponically grown produce often carries a stigma of tasting bad or bland among chefs. Colicchio cites the taste of Bowery’s arugula as the food that sold him on the technology and company.

Chef Tom Colicchio on the 18th season of Bravo’s “Top Chef.” Image Credits: David Moir/Bravo/NBCU Photo Bank / Getty Images

“I could sit here and tell you I listened to Irving’s stories about artificial intelligence,” the chef said in a 2020 interview. “I used only one set of intelligence to evaluate this investment and that was taste. For years, I’ve tasted hydroponics. People have tried to sell me on it, and I was never sold on it [ … ] Once I tasted how peppery the arugula was and Irving said, ‘I can make it more peppery or less peppery,’ it was really exciting.”

A little over a year after it signaled its interest in fundraising, the company took its first baby steps to the consumer market by signing a deal with Foragers, a small organic grocery store in Dumbo, Brooklyn and a second location in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. They were a good early partner, both in terms of size and the benefits indoor farming affords, as non-GMO produce is devoid of pesticides and does not have to be washed.

“I didn’t want it to be at Whole Foods,” says Fain, on finding Bowery’s first partner. “We’ve been thoughtful in how we scaled the business all along, because you’ve got to learn.”

As of 2021, the company sells its produce in more than 850 grocery stores, distributing to chains like Amazon Fresh, Giant Food, Hungryroot, Albertsons, Walmart, Weis and Whole Foods Market.

Yet as any modern consumer knows, the produce market is a competitive one, and no one wants to eat a tasteless veggie. Optimizing taste for consumers requires Bowery to perfect its own recipes for growing, and we’ll explore just how it does that in part two of this TC-1.

Bowery Farming TC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Produce development

- Part 3: Agtech engineering

- Part 4: Branding, finances and competitive landscape

Also check out other TC-1s on TechCrunch+.