There are several plastic clamshells sitting in front of me on a conference room table — around 20 or so boxes, labels facing forward, with a plate of turnips and a tub of those R&D strawberries we saw back in part two.

It’s a nice photo opportunity, backdropped by Bowery Farming’s impressive grow system and a good visual representation of the product’s life cycle. More importantly, it’s a reminder of how most people will ultimately interact with the company.

Bowery’s clamshells in the foreground and grow system in the background. Image Credits: Brian Heater

My position at TechCrunch afforded me the grand tour, of course — the whole Willy Wonka, clean suit coveralls and taste-testing experience. In the company’s FAQ, the answer to “Can I visit a Bowery Farm?” is a simple, “At this time, we do not allow visitors to our farms.”

It’s understandable, of course. While the farms themselves are a great visual, there are too many resources and health precautions required to worry about giving tours to outsiders. On my own visit, my guides were extremely cautious about what could and couldn’t be photographed — trade secrets and all.

Given the novelty of vertical farming, and that some stigma still exists against the taste of indoor-grown produce, Bowery’s branding strategy largely revolves around blending in.

Press coverage, like this feature you’re currently reading, is part of the outreach. The company opens itself to journalists and the occasional video camera knowing that putting its farms on visual display is a powerful way to unlock the fascinating story of vertical farming.

Ahead of my own visit, I watched a broad range of videos featuring vertical farms from all over the world. My playlist featured everything from Nordic Harvest’s newly opened 75,000-square-foot facility in Copenhagen, to the modular urban farming setups Brooklyn-based Square Roots creates inside a shipping container you can purchase for just $80,000.

The size, the scope, the potential impact — the mind reels. Vertical farming may be a nascent space, but it is growing rapidly, and the greenfield is being taken quickly.

Most consumers will never interact with a Bowery farm beyond reading an article or watching a clip online, and there’s nothing particularly wrong about that. The truth is that urbanites will almost never set foot in the place where our food is grown — that there’s a connection at all is a kind of win in and of itself.

Ultimately though, building that individual connection with consumers will determine the fate of Bowery in the ultra-competitive produce market. Branding is a high priority for the firm, particularly as it battles competitors like AeroFarms, which recently announced that it will go public via SPAC before failing to secure investor approval.

In this fourth and final part of the TC-1, I’ll look at how the company is trying to invent brand loyalty in the produce section, figure out its packaging, design its supply chain and, finally, seek a path to profitability against a broad competitive landscape.

Lettuce have a taste

Bowery sees opportunity in the boutique clamshells that have begun propagating across produce shelves in recent years — first in upscale markets and then more mainstream grocery stores.

Bowery’s design doesn’t scream “vertical farming.” You get the company’s name in big, bold letters, followed by “zero pesticides” and “grown locally.” The words “indoor grown” offer some insight, but in a world where many have at least set foot inside a greenhouse, the phrase could mean any number of things. The remainder of the notes, “no need to wash,” “fresher longer” and “non-GMO” are standard fare for the produce section.

Bowery Farming’s clamshell branding design, shown here with baby butter lettuce. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

Given the novelty of vertical farming, and that some stigma still exists against the taste of indoor-grown produce, Bowery’s branding strategy largely revolves around blending in.

It may well be a good one. Images of the farm as a large industrial warehouse may be a tough sell after 10,000 years of cultivating food on the earth.

Katie Seawell joined the Bowery team two years ago as chief commercial officer, after more than 15 years at Starbucks. Bowery offered her a unique opportunity to build consumer awareness and shape a narrative around a new technology.

Bowery Farming’s chief commercial officer Katie Seawell. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

“We’re still an emerging category,” she says. “But the awareness level is growing and there’s categories that have been around for a while now. If you look at tomatoes, tomatoes are a great example where they have been grown in greenhouses for a very long time. Talking about indoor farming, [this is not a] new thing to consumers. But what is compelling to them is the benefits of indoor growing.”

Seawell’s biggest hill to conquer is building brand loyalty, an admittedly strange concept in the world of produce. People don’t tend to purchase vegetables like they do shoes or soft drinks. They trust their eyes, mind their pocketbooks and, if they can afford to, look for the above buzzwords associated with organic produce.

“[T]here’s brand building that we’re doing,” says Seawell. “And that translates into how the packaging shows up on shelf; how we’re surrounding the consumer with the different messages at the right time and the right channels. There’s a very thoughtful kind of brand building strategy we have.”

It’s a multipronged approach that includes advertising and — in a non-pandemic era at least — food samples. While it’s probably safe to say that a bare leaf of lettuce doesn’t have the same sample appeal as, say, a piece of chocolate cake or a meatball on a toothpick, the company aggressively pursues marketing strategies like taste testing its produce against other store brands.

The taste test was, after all, enough to convert a food obsessed indoor-growing skeptic like chef Tom Colicchio in the company’s earliest days. Indeed, restaurants will play a role in getting the product in front of consumers, as will pop-ups from Colicchio and other initiatives by people like fellow chef José Andrés and Blue Hill founder David Barber.

Allergic to clamshells

For now, however, restaurants are a glancingly small piece of the puzzle as Bowery focuses almost entirely on retail channels.

“Restaurants for us today are a small portion of who we actually work with,” says Irving Fain, CEO and founder of Bowery Farming. “The food service segment is not a place we spend as much time today, but there’s no question that ultimately the food service opportunity is a very large opportunity for us in the same way that grocery retail is.”

Bowery Farming CEO and founder Irving Fain. Image Credits: DON EMMERT/AFP / Getty Images

Bowery’s plastic clamshells are, effectively, its greatest billboard. Their spot in the produce section will be many consumers’ first exposure to the brand, offering up the benefits of vertical farming in bite-sized marketing phrases.

But when you’re running a company that prides itself on being a net positive for climate, every action it takes needs to be viewed through that lens. What happens when the billboard touting your benefits is a net negative in itself?

“Plastic is something that we are absolutely thinking about all the time,” says Seawell. “On one hand, the plastic allows for the food safety and traceability of what is core to who we are. So, where we’re at today is, we are optimizing what we think is the best solution available in the market around plastic right now. It’s post-consumer recycled plastic — for every clamshell, there’s four plastic water bottles that we’ve used. We’ve used plastic that is more widely recyclable from municipality to municipality. That’s both on the top and the bottom of the clamshell.”

She acknowledges that plastic is a long-term problem. “We know it’s not enough,” she said. “Ultimately we are going to have to find [a solution], either through a distribution mechanism, a bulk mechanism [or] innovation and material. We will want to move beyond plastic over time.”

The company echoes the sentiment in a blog post titled, “Let’s Talk About the Plastic”:

Recycling is an imperfect system, yet it is still the most established way to ensure the reuse of materials in the widest number of places. And, if the ultimate goal is to ensure the longest product lifespan in the greatest number of cases, well, recycling is our best bet. Knowing our clamshells are made from recycled materials and can be widely recycled after use seemed like the most responsible packaging decision we could make. We don’t accept this as a perfect solution, just the one that makes the most holistic sense for right now.

Scale to fit

Proximity is also a big part of both the company’s connection to the consumer and its sustainability promise. Bowery isn’t factory farming so much as a farming factory. Large-scale farms constructed in retrofitted fulfillment centers afford it the ability to remove many of the traditional steps in the supply chain. Produce is grown, harvested and packaged all on site. Removing steps can dramatically expedite the time from farm to table.

Executive vice president and chief supply chain officer Colin Nelson casually notes that five minutes before our follow-up call, he was on the phone with Walmart, one of the company’s largest retail partners. They’re overbooked during a scheduled delivery, and suddenly Bowery has to figure out what to do with the produce it planned to deliver. “I’ve got product that I’m already harvesting for them for tomorrow morning,” he says.

Bowery Farming’s executive vice president and chief supply chain officer Colin Nelson. Image Credits: Bowery Farming

The company’s infrastructure isn’t built for the 3,000-mile, cross-country shipments many of us have come to expect from our produce. A system designed to move vegetables from farm to store within a day clearly has its appeal from the standpoint of freshness in a produce section where the apples you buy can often be a year or older.

But the promise of such quick turnaround creates its own issues. For one thing, scaling to reach new markets means building new farms rather than simply expanding existing ones.

“I think the biggest opportunity for us is that we are only really on the East Coast,” says Nelson. “We are only in two — and soon to be three — farms here. So the biggest impact that we can have is by being able to get accessibility into more urban environments really quickly and replicating the benefits that we see there.”

After proving itself a farm at a time, scale is now both the single largest challenge and opportunity for Bowery and the industry at large. Like manufacturing, with scale comes the ability to reduce prices. A four-ounce Bowery clamshell is currently $4 at my local Whole Foods. That’s slightly more than Organic Girl, a popular organic brand that runs $4 for five ounces, and the Whole Foods store brand, at $3.50 for five ounces, but it’s certainly within the realm of what consumers are willing to pay for organic produce.

But prices will need to drop if Bowery is to move beyond the niche of organic foodstuffs and deliver on the promise of providing healthy produce to food deserts and urban areas traditionally cut off from healthy food.

“We now need to scale ourselves much more quickly into many more places, initially around the country and ultimately, globally,” says Fain. “How do we ensure that we scale ourselves? We scale the company, we scale our cultural practices, we scale the quality of product, all of these things, maintaining the standards of excellence that we’ve set in the regions and in the farms that we’ve already built.”

Of course, it’s one thing to want to scale, and another to do it effectively. “When you start moving more quickly, when you start moving more broadly, it’s easy for those things to break down,” he says.

“We’ve put enormous amounts of technology and practices in place to ensure that the standards stay strong, but ensuring that we continue to make sure that they stay strong as we grow is going to be really important.”

Green with envy

AeroFarms co-founder and chief marketing officer Marc Oshima in Newark, New Jersey. Image Credits: ANGELA WEISS/AFP / Getty Images

In March, Bowery’s best-known U.S. competitor, AeroFarms, announced plans to go public via a SPAC deal with Spring Valley Acquisition Corp. at an equity value of $1.2 billion. No surprise there, really. Given the amount of hype they’ve generated in recent years, SPACs and vertical farming seem tailor-made for one another. Founded all the way back in 2004, AeroFarms was as good a candidate as any to go public, although the deal ended up falling apart despite approval from the SPAC’s shareholders in late August.

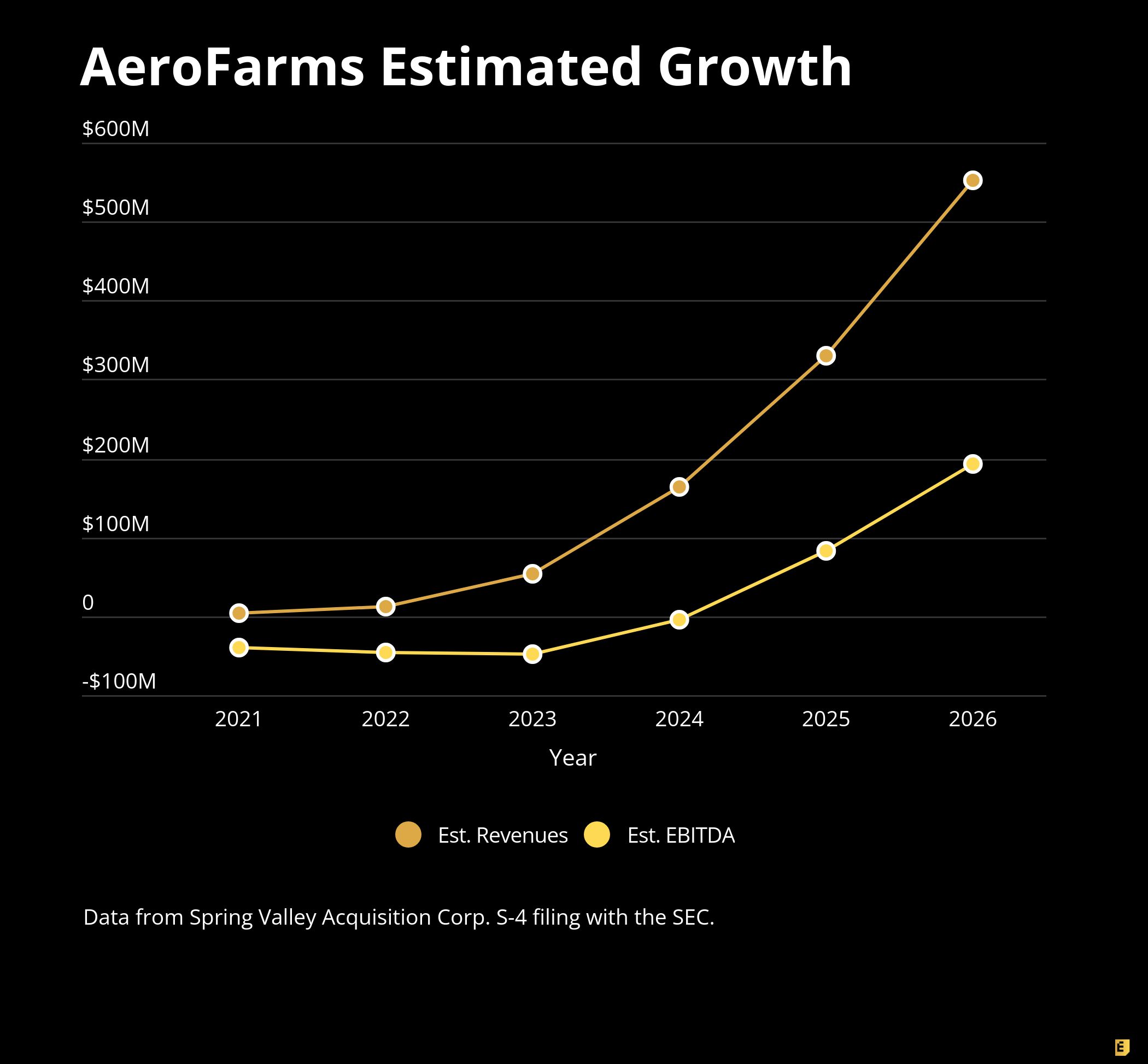

More than anything, a SPAC is an opportunity to inspect the financials of a private company. In the case of AeroFarms, specifically, it’s an opportunity to see how close the 16-year-old company is to profitability. The SEC filing has the company’s revenues in 2020 equaling $2.5 million, with losses of about $25 million. The company projects EBITDA revenue in the red through 2024, finally reaching profitability at $82 million in 2025. It’s a long runway for a company that has been in the game as long as AeroFarms has.

AeroFarm’s financial data as disclosed in Spring Valley Acquisition Corp.’s S-4 filing. Image Credits: Spring Valley Acquisition Corp.

In addition to its Newark location, AeroFarms has a farm in Ithaca, New York, and earlier this year broke ground in Danville, Virginia, just along the North Carolina border. Last year, it announced an ambitious plan to build a 90,000-square-foot R&D facility in the United Arab Emirates, courtesy of a $100 million investment from the Abu Dhabi Investment Office.

The company says it has grown 800 crops indoors, including blueberries, though it specializes in microgreens and baby versions of kale and arugula. It’s a more targeted approach than Bowery’s, but the company sports a number of major retail partners, including Whole Foods, Walmart, Fresh Direct, Shop Rite and Amazon Fresh. It’s an impressive list of names, but financials have remained a huge question mark, which ultimately led to the scuttling of the SPAC.

You need lots of greens to get into the black

For vertical farming, it’s a long game by any measure, due in no small part to the tight profit margins that come with growing produce at scale.

Profitability is another big question. Over in Japan, Spread was able to achieve profitability after hitting critical mass about a half-dozen years after starting production. God willing, it won’t take a major catastrophic event here like the Fukushima earthquake to push vertical farming into the mainstream.

Bowery is somewhat cagey when asked about profitability. Fain notes that, as a private company, it doesn’t reveal its financials, saying, “We have thought about and focused on the unit economics of this business and around profitability from the very earliest days. In fact, this was important to me before we ever raised a dollar, and that, for me, really comes from my career in technology over time.”

Bowery has secured nearly half a billion in funding to date on the belief that it will ultimately be able to generate profits on clamshells of lettuce. These aren’t iPhones we’re talking about here, of course, but like iPhones, there are a lot of different cost factors at play here, from labor expenses and energy prices in different markets to the overhead of building a farm.

Both Bowery and AeroFarms have addressed that last one, in part, by repurposing old buildings in many cases. AeroFarms’ Newark location, for instance, used to house an indoor paintball and laser tag facility.

AeroFarms’ Newark location, seen here, used to house an indoor paintball and laser tag facility. Image Credits: ANGELA WEISS/AFP / Getty Images

A huge question for the future is one of subsidies. The government issues tens of billions of dollars in farm aid each year. Such assistance could prove a strong motivator in countries aggressively pushing this technology (such as the UAE above).

But what about in the States? It’s not entirely out of the realm of possibility that farm aid can be redistributed, but with commercial farming lobbyists and deep-pocketed companies like Monsanto, it’s easy to predict plenty of pushback. The votes in the Senate, heavily skewed toward land-rich farming states, are daunting.

Growing up

At the close of our conversation, Fain gets reflective, noting how far the company has come in six years. “When I started, everybody looked at this as an ‘if,’” he explains. “It was like ‘if’ that ever becomes something, ‘if’ that ever works. It was this pseudo sci-fi fantasy way of growing food that one day maybe would happen.”

It certainly bears reflecting on just how far both Bowery and the vertical farming industry have come, evolving from a largely hypothetical notion to a product you buy at Walmart for $4 a box. Thus far, things haven’t played out precisely as Dickson Despommier dreamed in the pages of “The Vertical Farm,” but the progress the industry has made in the space between the book’s first printing and its 10th anniversary edition is impressive in the physical world, where progress too often moves at a glacial pace.

Still, the newly printed final chapter of the book doesn’t end on a celebratory note, but rather one of great urgency:

We cannot afford to continue as if nothing is wrong, but if we do, then sooner or later we will suffer the same fate as the million other species whose extinction we have already caused. Those who are not afraid to strive toward improving the human condition create the future. Helping a scarred, fragmented world to heal itself by simply leaving it alone may be the only strategy that guarantees our long-term survival.

The tenor of the passage is one of great urgency in the face of the looming existential threat that spurred the concept of vertical farming in the first place. It’s one that ought to be present in every step of the process as we determine whether the sum total of these technologies are, in fact, the world-changing solutions they purport to be.

At best, vertical farming will be a piece of the puzzle, something we can slot alongside other helpful technologies aimed at cleaning up this global mess we’ve created. At least the wasabi will be real.

Bowery Farming TC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Produce development

- Part 3: Agtech engineering

- Part 4: Branding, finances and competitive landscape

Also check out other TC-1s on TechCrunch+.