When it comes to user-interface design, 911 is about as good as it gets. It’s the “most recognized number in the United States,” Steve Souder, a prominent 911 leader, points out. Simple, fast, and it works from any telephone in the United States. No matter what the emergency is, the call takers on the other side will triage and dispatch assistance.

I’ve taken that ubiquity and simplicity for granted over the past three parts of this EC-1 on RapidSOS as we’ve looked at the startup’s origin story, business and products, as well as its partnerships and business development engine. The company is deeply enmeshed with 911, which means that the prospects of 911 as a system will heavily determine the trajectory of RapidSOS in the coming years, or at least, until its international expansion hits scale and it isn’t so dependent on the U.S. market.

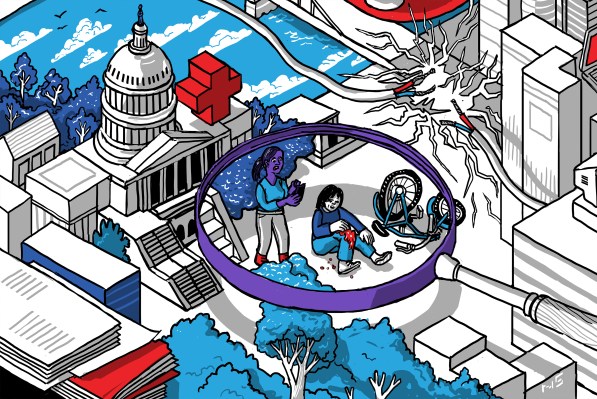

Right now, a $15 billion funding bill to invest in NG911 has been proposed in Congress as part of the LIFT America infrastructure bill that is currently winding its way through the appropriations process and negotiations between Democratic and Republican leaders.

Now, you might think, “911, how could they screw that up?” But this is America, and you’d be surprised.

Despite the daily heroic work of tens of thousands of 911 personnel who keep this brittle system afloat, the reality today is that America’s emergency call infrastructure is in a perilous state. After more than a decade of heavy advocacy, the transition to the “next generation” of 911 (dubbed NG911), which would replace a voice-centric model with an internet-based one designed around data streams, has been trundling along, with some early traction but little universality.

As a Congressional Research Service report described it just a few years ago, “funding has been a challenge, and progress has been relatively slow.” Three years later, the words are just as true as they were then.

Given that RapidSOS’ future ultimately relies on a competent government capable of providing core infrastructure, this fourth and final part of the EC-1 will look at the current state of 911 services and what their prospects are, and finally, how one should ultimately judge RapidSOS given all that we have seen.

The three-digit number that feels like it is three-digits old

911 was invented in the late 1960s to unify America around one emergency number. Early forays to create emergency lines had sprouted up across cities and states, but each used their own system and telephone number, creating massive complications for travelers and people living on jurisdictional boundaries. President Lyndon Johnson’s 1967 crime task force recommended creating a single number for emergency calls as a crime-prevention tool, and on February 16, 1968, the first 911 call was dialed in Haleyville, Alabama.

Unsurprisingly given the era, 911 calls were designed around voice. A caller connected with a call taker and explained where they were and what the emergency was. The voice interface was and remains flexible and iterative. Rather than, say, a dial menu with options for different types of emergencies (“If you are being murdered, please press *6 and wait on the line”), voice allowed for quick transmission of critical information. Crucially, it also allowed the call taker to guide the caller on steps they could take while waiting for help, and also to offer emotional comfort during a stressful time.

The world has changed since the 1960s, though, with the internet having grown from a few nodes on ARPANET to billions of devices globally. All kinds of devices have information and sensing functions that can be useful in emergencies. Smartphones have GPS and health data that can provide critical context during a medical crisis. Home security systems can sense intruders breaking a window, even when no one is home. Fire sensors on power utility poles can detect the scope of a wildfire, and much, much more.

Souder, who is also on the board of advisors of RapidSOS, says, “I like to say that the only thing about 911 of the future compared to today is the number … everything will be different, and technology is driving so much of what we do.” Referring to RapidSOS, he said, “I don’t think they ever realized that they would have as many applications as it is proving to be.”

Yet, 911 is still almost exclusively designed around voice today. A home security system that generates an alert and has a live video stream doesn’t get sent directly to a public safety answering point (PSAP) for processing. Instead, the data is typically first routed to the company’s own security operations center, where a human operator will view the alert and video and then directly dial 911 on the device’s behalf and verbally explain what they are seeing — a literal game of telephone.

There have been some meager attempts to improve the system over the decades. The FCC, through its Enhanced 911 (“E911”) initiatives, has mandated that telecom companies must provide triangulated location data of a mobile phone user within a range of 50 to 300 meters. It was a useful stop-gap measure, but that circumscribed area is far too large to be all that useful.

The more ambitious plan is NG911, a set of standards that would transition 911 away from telephone calls to internet-based protocols that could transmit data — as is common with any web app. For instance, if a 911 call taker were to respond to a home break-in, the home security system could proactively offer a live video feed of the situation to both the call taker and police. Health profile data (such as the data we talked about in part three) could automatically be sent to responding paramedics, which would be extremely helpful for people with diseases and allergies that require special care.

For RapidSOS, the transition to NG911 would be hugely beneficial. Its platform gains utility with every PSAP that can accept richer data. That means the company can help more people, and ultimately, build an even stronger business in the United States. In a way, much of the company’s integrations and products discussed in earlier segments of this EC-1 are “hacks” designed to get around the voice-centric nature of today’s original system.

Why haven’t we already migrated to this new architecture? The standards for these protocols have been written and tested, and in fact, much of the core technology has been around for a decade or more. The National Emergency Number Association (NENA) just published the third version of its i3 standard, which governs NG911 technology and ensures that software and hardware is interoperable. So the standards and the technology are already ready to handle robust location and many more rich data streams.

The key block has been funding, and it’s not a happy story.

$9.11

911 is operated in a decentralized fashion by local agencies that are funded through taxes and also by the 911 infrastructure fee attached to some telephone bills. There are thousands of PSAPs across America — in fact, the system is so decentralized that the FCC undertakes rigorous surveys to get an accurate count of them. By recent counts, they number around 5,700 individual agencies.

These call centers receive relatively threadbare operating budgets from the government for staffing and maintenance costs. Capital investment in general is minimal — many 911 systems, particularly in more rural parts of the country, have never been upgraded from the original hardware installed five decades ago.

That has made the transition to NG911 treacherous over the past decade. Upgrading these systems requires a massive investment in new hardware and software as well as extensive training for staff. Cash-strapped agencies are hard-pressed to find a source of heavy, one-time funds. Unlike roads or bridges, where toll revenue could potentially underwrite a bond issue, there is no usage fee to using 911, which precludes most financing mechanisms other than general obligation bonds underwritten directly by the government.

Worse, there has been a widening scandal of state and local governments diverting 911 fee revenue to non-emergency services. It’s become so alarming, in fact, that Congress directed the FCC to launch a strike force earlier this year to investigate where the money is going.

More positively, some states and municipalities have been proactive in investing in this infrastructure themselves, and indeed, there has been a notable uptick in NG911 systems over the past few years. The National 911 Program and the National Association of State 911 Administrators (NASNA) annually conduct a survey and publish a report on 911 usage. The most recent edition covering 2019 shows that more than 2,000 PSAPs now use some IP-based infrastructure. That was a new milestone, but represents only roughly a third of all PSAPs in the country.

Everyone in the industry agrees that the big push for change has to come from Congress. For the past six years, Congress has regularly debated a fund for moving 911 services forward, and the Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus, led in the Senate by Amy Klobuchar and Richard Burr and in the House by John Shimkus and Silicon Valley’s Anna Eshoo, has advocated for swift investment. Industry veterans I talked to said that there is no partisan opposition to these plans, and in fact, nearly all funding for the system enjoys wide bipartisan support.

Yet, the funding has never been approved. The urgency, though, has become more acute following the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw 911 centers flooded with calls as people asked about coronavirus symptoms and how they should respond.

Right now, a $15 billion funding bill to invest in NG911 has been proposed in Congress as part of the LIFT America infrastructure bill, which passed the House with Democratic support in a mostly party-line vote.

One unique characteristic of the bill in its current form is that it would not require matching state or local funding in order to receive a federal 911 upgrade grant. That’s unusual, and means that all municipalities across the country could effectively put together a grant proposal — vitally important after COVID-19 wiped out large segments of local tax revenue last year. Given the existing NG911 standards available in the industry, upgrades might be faster than expected, since many of the systems have already been tested and are ready for deployment.

Trade associations and industry lobbyists told me that they are cautiously optimistic about the funding’s chances this time around, although recent notes from Capitol Hill indicate that dedicated funding has not yet made it into the final infrastructure bill being negotiated by Congressional leaders.

Rapid Startup One Senses

Based on a cursory records search in major filings databases, RapidSOS hasn’t hired a congressional lobbyist or made financial contributions to federal candidates so far, which the company also confirmed. That’s frankly surprising, given how these potential appropriations could radically augment the trajectory of its business.

The good news is that after years of delays, the momentum behind transforming these systems seems to have catalyzed, and RapidSOS is primed to take advantage of the moment.

Michael Martin, the company’s co-founder and CEO, said in part three: “In so many ways, this was the story of just the community coming together, but also being at the right place at the right time.” He was referring to the proliferation of smartphones and other devices and how that affects 911, but it also applies to NG911. The company may once again be perfectly timed to take advantage of a once-in-five-decades moment to be at the center of only the second generation of 911 technology. It’s little wonder then that VCs have been pouring money into the company in the past year.

In many ways, RapidSOS is the archetype of the classic startup story. Martin and his co-founder and CTO Nick Horelik have assiduously worked to build a system ideal for this industry and this moment. It’s a process that has had excruciating ups-and-downs and would have dissuaded almost certainly anyone else without the same level of fortitude and willpower to keep trudging along. But in the end, RapidSOS is that mélange of grit plus luck with a white-hot focus on willing a better world into existence. In the end, if you ever dial those three numbers, it might just save your life too.

RapidSOS EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product and business

- Part 3: Partnerships

- Part 4: Next-generation 911

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.