Luis von Ahn, an entrepreneur who has dedicated his career to scaling free education, has probably annoyed you more than once. In fact, you’ve likely been annoyed by his work dozens and maybe hundreds of times over the years.

A decade before he co-founded the whimsical and language-learning app Duolingo, one of the most popular education apps in the world with over 500 million downloads and 40 million active users, he was building the technology that would become CAPTCHA, those human-annoying but bot-preventing little tests that pop up when registering or logging in to popular internet services like email.

It may seem like a radical pivot, but in fact, the lessons of how to create useful security tests at scale for consumers would one day offer the core DNA for building one of the most successful edtech companies in the world. The immigrant entrepreneur would soon learn himself that crowdsourcing, language and a willingness to adapt and ignore critics could change the face of an industry forever.

CAPTCHA’ing a market

Von Ahn grew up in Guatemala City, where he saw firsthand the wretched state of public schools in impoverished countries. His mother spent most of her income sending him to “fancy private school” as he puts it, and he estimates she spent over $1 million on his education over his lifetime. The price tag weighed on him, and he knew he wanted to broaden access to education in the future.

After attending Duke as an undergrad, von Ahn was an enterprising first-year computer science Ph.D. student at top-ranked Carnegie Mellon University when he attended a talk by Yahoo’s chief scientist about 10 of Yahoo’s biggest headaches. One issue stood out: hackers were creating bots that register thousands of email addresses to send spam.

Inspired and full of immigrant grit, von Ahn and a team led by his then-adviser Manuel Blum created a nifty little test that could distinguish between bots and humans. The test, called a CAPTCHA, presented squiggly, ink-blotted words whenever a user tried to log in. Computer vision at the time couldn’t read the obscured text, but humans easily could — creating a useful signal. The deceptively simple test worked, so von Ahn, then a 20-something student, gave it to Yahoo for free, not understanding the value it would one day have.

Luis von Ahn, the inventor of CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA, and co-founder of Duolingo. Image Credits: Duolingo

A fire was lit. With Yahoo as a distribution channel, CAPTCHA tests exploded in popularity, becoming an almost universally recognizable security checkpoint feature. At their peak, people spent 500,000 hours a day typing up to 200 million CAPTCHAs around the world. About 10% of the world’s population had recognized at least one word, von Ahn estimates.

For all the technology’s success, though, there was a downside. “During those 10 seconds while you’re typing in a CAPTCHA, your brain is doing something that computers can’t do, which is amazing,” von Ahn said. But the tests were annoying and pointless, so he wondered, “Could we get those 500,000 hours a day to do something useful for humanity?”

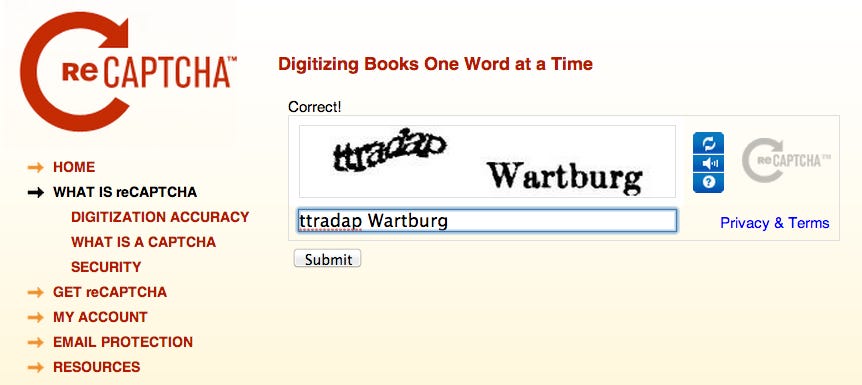

So in 2005, he launched reCAPTCHA. These new tests would have the same goal of CAPTCHA, but with a twist: the prompts would all be scans of books. Users would complete the security test while also helping to digitize books for the Internet Archive.

The early design of reCAPTCHA. Image Credits: Duolingo

This time, von Ahn knew his nifty idea was worth something. In 2009, he sold reCAPTCHA to Google, a transaction conducted just a year after the internet giant had purchased a license to one of his other research projects, a game focused on image labeling.

Luis von Ahn presenting about reCAPTCHA and CAPTCHA, two of his iconic inventions. Image Credits: Duolingo

The acquisition offered not just a monetary award (exact terms of the deal were not disclosed), but also suddenly garnered von Ahn serious clout in the industry just a few years after acquiring his Ph.D. Yet, instead of taking up tenure at the tech company, he stayed local in Pittsburgh and became a computer science professor at his alma mater.

Entering the world of education as a professor felt like an answer to his original dream of expanding access to education. What von Ahn didn’t know, though, was that his iconic work was simply foreshadowing. Carnegie Mellon, crowdsourced translation and even Google would all play a role in his next project as well, albeit in wildly different ways: incubation, failure and investment. For him, the success of two tools that used language as a barrier was the beginning of a long journey into discovering if, and how, language could instead be a bridge. It was an insight that would grow into a startup valued at $2.4 billion with the goal of making language learning fun: Duolingo.

Duolingo’s first words

In 2011, edtech startups such as Coursera and Codecademy were popping up — companies that today are valued as multibillion-dollar businesses. The rise of iPads and tablets in classrooms gave permission to founders who believed the future of education was on the internet. Enthusiasm was boiling, and virtual instruction felt like a nascent, but ambitious, place to bet on.

Von Ahn, meanwhile, was becoming weary of teaching computer science in a traditional classroom, which he found stifling compared to the potential of computers to democratize education. So, he looked for an enterprising young immigrant in one of his classes to work with — wanting to bet on someone the same way Blum once did with him. Von Ahn linked up with Severin Hacker, his Ph.D. student from Switzerland, and they began sketching out an idea for a web-based education platform.

An early photo of Severin Hacker and Luis von Ahn, the co-founders of Duolingo. Image Credits: Gina Gotthilf

Compared to the colorful and bold von Ahn, Hacker is a quiet, focused person. But, he’s surprisingly hilarious. When he’s in a meeting that has devolved, he mutters, “This meeting has peaked,” and leaves. When he introduces himself, he acts out his unique name: He pretends to sever his arm, and then proceeds to type hastily on a computer.

When the duo teamed up, they had to find a subject to teach. Hacker was interested in coding, while von Ahn was considering math or programming. In the end, they landed on language learning, far from the subjects they had the most expertise with.

Von Ahn thought again about the opportunities he had growing up in Guatemala and knew that his English language skills had helped him in an outsized way. “I love math, but if you learn math, math itself can’t make you any money,” von Ahn said. “You learn math to learn physics to become an engineer, whereas knowledge of English directly improves your income potential in most countries of the world.”

He wasn’t the first to realize this. Millions of people were spending money on language-learning services, and the market then, inclusive of all languages, was worth some $82.6 billion. Even better, the hottest language-learning software in town a decade ago was Rosetta Stone. “It had a CD for literally $600 or $700 and no app,” von Ahn said.

Hacker and von Ahn saw an opportunity, and the solution was simple: Duolingo could win over consumers if it could become a free, effective language-learning app.

How hard could it be for two technologists with no linguistics background to change the entire field? Thankfully, von Ahn was used to turning to crowds of people when in doubt.

Severin Hacker and Luis von Ahn, the co-founders of Duolingo. Image Credits: Gina Gotthilf

Crowdsourced translation

In front of more than a thousand people at TechCrunch Disrupt in 2012, von Ahn presented a trailer of their new product, “Duolingo: Learn a language by translating the website.” The company was launching its first product out of private beta, which alone had attracted an exclusive group of 125,000 people.

“Since the dawn of humanity we’ve been passing information from one person to another through common language; Unfortunately, you can’t communicate with others without knowing or learning their language first,” the trailer continued. “A similar issue has manifested on the web, where text can be penned in dozens of languages, each of which demands a reader’s fluency.”

Luis von Ahn, co-founder of Duolingo, presenting at TechCrunch Disrupt NYC 2012. Image Credits: TechCrunch

Much as he had with reCAPTCHA, von Ahn saw a new two-sided marketplace that could be connected through technology. On one side were users looking to use the web to learn a new language. On the other side were websites, news agencies, marketing firms and others who wanted to translate their content into multiple languages as quickly and cheaply as possible.

Here’s how Duolingo worked at launch: A native Spanish speaker who wants to learn English would be given a sentence from an English website to translate into Spanish. Those prompts would be tuned to expertise level, so beginners wouldn’t be scared into quitting and advanced speakers wouldn’t be bored. If a speaker was lost, they could click to receive possible translations for words they didn’t know. After the exercise, Duolingo would then help the user practice any new words they stumbled upon through examples and flashcards.

Thus, Duolingo would be the elegant solution that could solve two problems with one product. If 1 million users logged into Duolingo to learn, the entirety of English Wikipedia could be translated to Spanish in 80 hours. To pay its bills, Duolingo would source a group of paying clients, to which it would sell user-generated translations while keeping it free for learners.

“No ads, no hidden fees, no subscriptions, just free,” the trailer continued.

Von Ahn’s reCAPTCHA fame was a deal sweetener for Duolingo right from the start. The connection helped Duolingo quickly become a press darling, allowed von Ahn to give international presentations on the future of education and added a layer of legitimacy that would garner Duolingo its first term sheets.

Monolingo VCs: All Valley, no edtech

Before that demo and the crowds though, Duolingo had set out to raise a $3.5 million Series A in 2011. Even for a second-time founder with a recent exit to Google, von Ahn had to overcome the hesitation of VCs around education endeavors — and also startups based outside of Silicon Valley. Edtech-focused venture capital funds such as Reach Capital, GSV and Owl Ventures were years away from being founded, and mainstream Silicon Valley had pretty much written off edtech altogether.

Bing Gordon, a former partner at Kleiner Perkins (then called Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers or KPCB), was intensely interested in the gamification of content and repackaging the traditional lecture even back in 2009.

“My education thesis pretty much got the reaction of ‘you’re wrong, good luck,’” he said. (Kleiner Perkins would go on to lead Duolingo’s $20 million Series C, as well as invest in edtech companies including Newsela, a unicorn, and Coursera, which recently went public).

But Duolingo had the advantage of von Ahn as a founder. Silicon Valley may not have been ready to bet on a Pittsburgh language-learning company launched by co-founders with no experience in language learning, but it was ready to bet on a repeat founder with multiple exits.

“We got term sheets from everybody,” von Ahn said. “Many years later what I heard [from them was] ‘Look, we had no idea what the hell you were going to do, but you have sold two companies to Google. So, whatever. We’ll invest in you.’” Google Translate was even a rumored acquirer before Duolingo was barely a year old.

Von Ahn picked a term sheet by Brad Burnham, who was leading the investment on behalf of Union Square Ventures. In addition to capital, there were two advantages Burnham offered. First, USV was one of the few firms that didn’t require Duolingo to move to Silicon Valley post-investment. Today, the majority of Duolingo’s 384 employees still live and work in Pittsburgh, with additional offices in New York City, Seattle and China.

Second, Burnham was one of the few investors Duolingo talked to at the time who believed in education as an investment thesis. “The challenge for all of us is to find ways to exploit technology to reduce the cost and increase the accessibility of education,” he wrote back in 2009.

Burnham’s tone around accessibility jived well with von Ahn and Hacker’s mission. With USV on board, which was the same firm that gave a first check to Twitter, Etsy and Zynga, Duolingo got some Valley prestige. Ashton Kutcher and author Tim Ferris jumped into the round as well, and it would take less than a year until Duolingo went and raised five times the capital in its Series B.

Venture capital gave Duolingo a cushion — and eventually lifeline — that would let it prioritize product over monetization for years to come.

The 2012 design aesthetic of Duolingo. Image Credits: Duolingo

The interns who pivoted a startup

Duolingo’s app has garnered many awards, and it’s more well known than any of Duolingo’s other products, such as its proficiency tests. Yet, its iOS app was an accidental success pioneered by two then-interns.

Back in 2011, websites remained the dominant platform for tech startups, with mobile apps just becoming the mainstream success we know well today. Von Ahn, thinking people would never want to type translations or sentences on their phones, thus focused on building for the desktop. Less than a year after its public launch, Duolingo attracted over 300,000 users to its site with an average engagement time of 30 minutes per day.

Other consumer startups were taking a similar approach, but some flirted with the idea of companion apps. The apps would check a box for startups to be mobile-friendly, but in reality they would only have a fraction of the desktop site’s functionality. Even though Duolingo saw its future in translation and its desktop site gaining purchase, it didn’t want to be behind the trend. The co-founders thought a flashcard app would be a nice companion app, and assigned two just-hired interns to start building a prototype.

The two interns, Tyler Murphy and David Klionsky, had both never owned a smartphone. En route to a Duolingo website launch party in New York, they bought an iPhone to study on the road and get to task.

Tyler Murphy and David Klionsky, two interns responsible for creating Duolingo’s successful app. Image Credits: Duolingo

“We studied a lot of apps that don’t exist anymore,” Murphy said. Path was well-designed, Evernote was hot, but Instagram was truly a “North Star for what mobile experiences should look like.” Instagram had a full in-app experience with a scrollable feed filled with nearly everything one could get from Facebook.

Murphy wanted Duolingo to offer a similar top-notch experience, with a free, fully functional app instead of simply a flashcard program. He also wanted Duolingo to have the sleekness of one iconic app, so he pushed for the team to avoid creating language-specific companion apps.

“At the time, it didn’t seem like that revolutionary of an idea,” von Ahn said. “In retrospect, I think this is one of the best decisions we ever made.”

Tyler Murphy, Luis von Ahn, David Klionsky and Severin Hacker looking at the early Duolingo iOS app. Image Credits: Duolingo

By having one consistent experience for all users, Duolingo was forced to think much more strategically about exactly what its offering was to users. “It forced us to identify what is the core experience of Duolingo — and it’s this skill tree that you unlock to make progress and tap on those to make a lesson and after the lesson you get some celebrations,” Murphy said. “It forced us to identify that that is our bread and butter.”

He began to strip away the fluff, and Duolingo began to look like the Duolingo used by millions today.

Within a week after launching its iPhone app, Duolingo became the most downloaded app in the education category. Within a year of launch in 2013, it won Apple’s iPhone App of the Year. The year after, it won TechCrunch’s Crunchie award for education startup of the year.

Duolingo won App of the Year from Apple in 2013. Image Credits: Duolingo

Winning Apple’s App of the Year was when von Ahn and Hacker realized that Duolingo was going to be bigger than they thought. “My previous companies were just like ‘Look, this is kind of cool. I’ll do it,’” von Ahn said. “But Duolingo? I’m willing to spend decades on this. This is edtech, it’s slow [and] it was not a company I was interested in selling.”

Canceling monetization

While the wins were energizing, one of von Ahn’s early concerns was quietly becoming true. Since he thought that people wouldn’t want to type out translations or long sentences on their phones, he nixed the website translation monetization model from the app. At the same time though, nearly 80% of Duolingo’s traffic was coming from mobile. With the most successful part of its product having nothing to do with monetization, Duolingo had a problem.

“The way we’re going to make money was solely on the website, but the app was the future,” von Ahn said. “That’s not so good.” The prospects of the translation strategy that had worked so well for von Ahn in the past were suddenly gloomy. The startup was only able to close Buzzfeed and CNN for its translation services, and new translation companies were constantly undercutting them with lower prices.

Meanwhile, Duolingo was buffeted by a number of language-learning competitors such as Livemocha, PlaySay, Voxy, italki, MindSnacks and Busuu, which forced the company to find a way to afford staying free and remain differentiated enough to retain users.

Karin Tsai, an early engineering hire at Duolingo and now a director of engineering at the company, was in the strategy meeting when the team decided to no longer use translation services as a monetization strategy.

“There’s just a misalignment between having our learners learn through translating and providing value translating, versus actually really wanting to teach them a language well,” she said. “We really wanted to be able to do the latter and the fear was, if we had to do the former and translation was how we built our business, we would always be incentivized to do the wrong thing when it comes to learning and teaching better.” Plus, she added, Duolingo was “nowhere near profitable” with language translation as its monetization engine.

Karin Tsai (R), director of engineering, at Duocon in 2019. Image Credits: Duolingo

Von Ahn doesn’t think crowdsourced translation failed him, and still believes that it has a role to play in humanity — just not for teaching. “When somebody is typing in a CAPTCHA, your relationship with them is for 10 seconds, it doesn’t matter,” he said. “With Duolingo, you have a long-term relationship with them. And so it’s a different beast, I think.”

The accidental app success led Duolingo to shut down its translation services business by the end of 2013. Instead of finding a new route to monetization, von Ahn explained to investors that the company would focus on product development and scaling user growth, with the hope of bringing in revenues one day in the future.

Murphy, the intern who would go on to become the chief designer at Duolingo, remembers that the early philosophy of Duolingo changed then. Without the translation hook, the company had to truly deliver an exceptional product that could get high engagement rates and loyal customers. “The early philosophy of Duolingo wasn’t just like, ‘Let’s just take Rosetta Stone and make it free,’” he said. “It was really like people aren’t falling in love with learning like a lot of us are, so how do we make a gateway drug?”

Answering that question put product growth at the heart of the company’s engineering culture. It paved the way for the language-learning company to experiment with gamification, education, and of course, as we’ll learn in part two of this EC-1, a passive-aggressive little green owl that would become a beloved icon.

Duo, Duolingo’s beloved mascot. Image Credits: Duolingo

Duolingo EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product-led growth strategy

- Part 3: Monetization

- Part 4: New initiatives and future outlook

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.