As its meandering route to monetization will demonstrate, Duolingo isn’t mission-oriented, it’s mission-obsessed.

Co-founders Luis von Ahn and Severin Hacker never wanted to charge consumers for access to Duolingo content, a purpose imbued throughout the company’s culture. For years in order to work at Duolingo, you had to be comfortable with joining a company in Pittsburgh that was in no rush to make money. The startup, filled with education enthusiasts and mission-driven employees, became “very college pizza vibes,” Gina Gotthilf, former VP of Marketing at Duolingo, described. Everyone was against making money and having structure — some employees even threatened to quit if Duolingo ever charged a cent to users.

“One thing that recruited me was this brilliance that we can kill two birds with one stone,” she said, referring to Duolingo’s original translation-service business model we talked about in part one of this EC-1. “It was obviously tied to Luis’ thinking and reCAPTCHA and it was magical and brilliant.”

Free may not have paid the bills, but it did come with a valuable upside: growth. By 2017, Duolingo would boast having 200 million users, which was double von Ahn’s goal when he first launched to the public on the TechCrunch Disrupt stage.

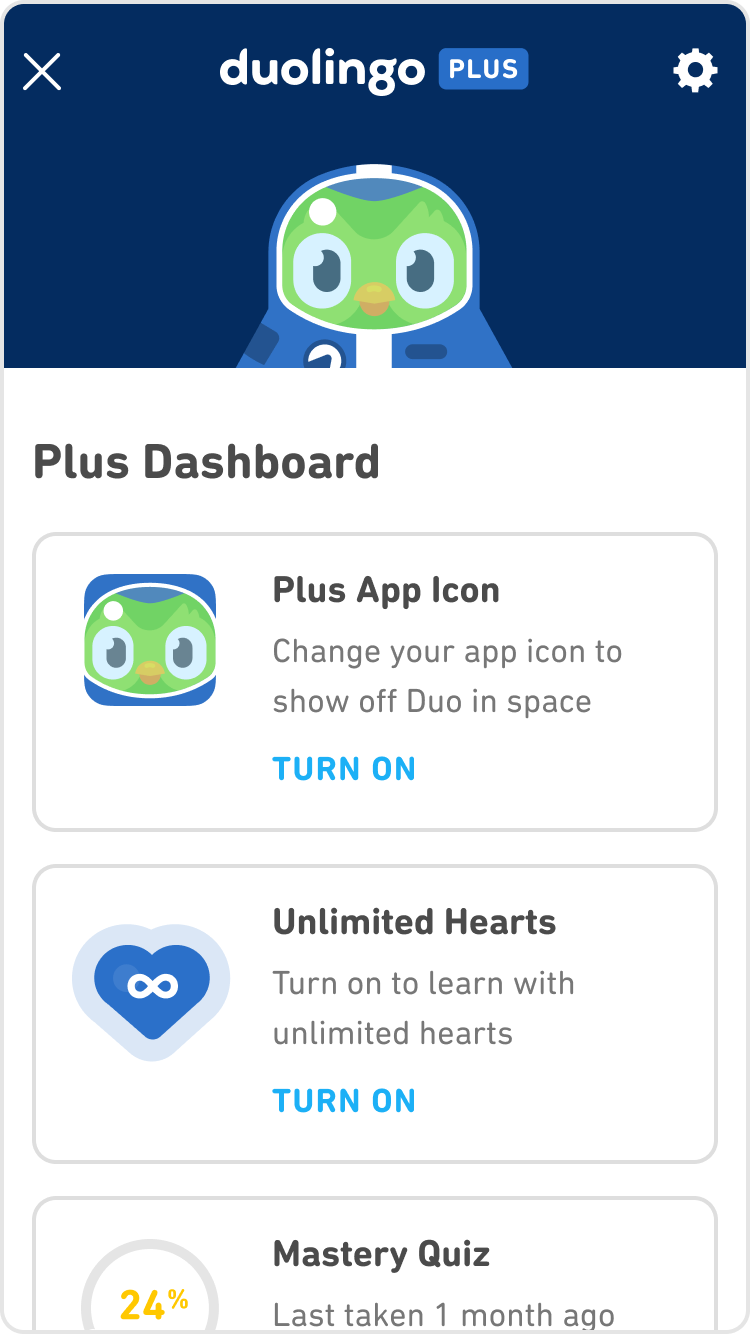

Duolingo launched saying it would never do advertisements, subscriptions or in-app purchases — approaches that now all exist on the platform. Today, Duolingo has a simple freemium business model that is remarkably unconventional. It has a free version with all of its learning content, and it charges a subscription of $6.99 per month for paywalled features such as unlimited hearts, no advertisements and progress tracking. It also has a number of other revenue streams it’s developing, such as language proficiency tests.

As we’ll explore, Duolingo’s route from anti-business rebel to conventional consumer subscription is complex, full of twists and turns. While Duolingo never wanted to look like other edtech companies, as we saw with its product strategy in part two, it turns out that evolving from college pizza vibes meant that it would have to take a page from its peers.

Duocon, Duolingo’s new conference to celebrate education and language. Image Credits: Duolingo

Business only speaks one language: Money

“They had users and in Silicon Valley, there was this notion that if you have users, you can turn anything into money,” said Bing Gordon, the Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB) partner who led Duolingo’s $20 million Series C in 2014.

“This was not very controversial back then, at least with investors,” von Ahn said. “This became controversial for us once we raised a ton of money, and we still weren’t making more money.”

While the company’s investors were relatively lenient in the early years, patience was starting to run thin. In June 2015, Duolingo raised a $45 million Series D round led by Laela Sturdy of Google Capital (later rebranded CapitalG), valuing the company at $470 million. She invested because of Duolingo’s growth and engagement numbers, but confronted von Ahn with some direct advice.

“She said to me, ‘Look, it worked for you to continue getting bigger and bigger checks from venture capital,’” von Ahn said. “‘But this is the last time it works for you … if you’re trying to con people, you cannot con anybody bigger than us [at Google].’” Duolingo’s valuation wouldn’t just be at stake next time it went fundraising on Sand Hill Road — its very survival would be as well.

Looking back, Sturdy said that she always “had confidence that they would come up with a revenue model” because of Duolingo’s passionate and organic users.

When a startup chooses to raise venture capital, it sets itself on a heavily-prescribed course. Suddenly, success isn’t defined merely as cash-flow breakeven with a long-term sustainable business. It has to be an exit of some sorts, and a big one at that. While Duolingo used venture as a lifeline to fund its product development, venture also came with pressure to become a billion-dollar company, or more. And that meant making revenue, not just growing engagement.

Von Ahn says his conversation with Sturdy is what really changed his mindset about money. After the Google check hit Duolingo’s bank account, he and Hacker began thinking about ways to make Duolingo as much a monetary success as it had been an educational one.

Duolingo’s Pittsburgh HQ. Image Credits: Duolingo

Dr. Ahn or: How I learned to stop worrying and love the revenue(s)

“It was clear that Luis didn’t have commercial instincts, he had cultural instincts and a deep focus on learning,” said Gordon. “[When we invested] Duolingo predicted it was on the verge of revenue growth, and it turned out it was not on the verge of revenue growth.”

What Gordon is alluding to was a litany of monetization attempts in Duolingo’s past. Translation, which helped von Ahn’s previous two startups, didn’t work when applied to language-learning services, and the company only secured two customers before ending the service. Business partnerships, such as a relationship with Uber to certify and train drivers in Brazil to speak English, didn’t catch fire.

In 2016, von Ahn wrote a blog post about the state of monetization at Duolingo after a user offered to support Duolingo after hearing about financial troubles. He explained that the startup was expensive to run, estimating that it spent $42,000 per day then on servers, employee salaries and other operating expenses. The cost was only growing, with users doubling every few months.

“Many people in the community have strong opinions about how we should or shouldn’t monetize. Some think we should try ads, others think we should sell lingots [the company’s in-game currency] for money or simply have a donation button,” he wrote. “And for every idea there are many who are ready to grab their torches and pitchforks because they think doing it would be a capital sin.”

Von Ahn went on to explain that the startup would begin a period of mass experimentation to figure out new ways to monetize, with the promise that the “experiments will be carefully thought out and scientifically measured to ensure that Duolingo remains equally engaging and that someone who doesn’t have a bank account can go through the entire learning content without ever paying us a single cent.”

When Duolingo decided it would monetize, “there was a lot of concern [internally] because people generally just think money makes people evil,” said Karin Tsai, director of engineering and an early employee at Duolingo. “It was a very tricky thing to navigate.” Employees were worried that the mission they had joined would directly clash with the new focus on monetization. Similar to how Duolingo sunsetted its translation business model after realizing the lack of pedological value, other business models had the same caveats.

One product that emerged from these experiments was a Test Center certification program that would verify a user’s language proficiency and later be rebranded as the Duolingo English Test. It originally cost $20 to take and is now priced at $49. That product has become an inadvertent star over the past year in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic, when in-person testing centers had to close down and virtual options were the only alternative.

Another experiment was periodic in-app advertisements sprinkled into lessons. This approach, which is common with many free-to-play games, is not a great experience and could harm pedagogical value. It also wasn’t popular internally. “If we start having ads, will we start advertising everywhere? How will we control our future selves and the people who come after us to make sure our product doesn’t devolve into a huge monetization grab bag?” Tsai said. “Honestly, we still wrestle with some of these issues.”

Product experiments were useful, but the company needed to aggressively expand its talent bench if it was going to monetize successfully. Duolingo went on a hiring spree in early 2016, growing the new products and monetization team from 50 to 100. One of those hires was Bob Meese, a Pittsburgh native and former head of business development at Google Play Games who joined Duolingo as vice president of business.

He didn’t look like most of the rest of the folks at Duolingo who had joined up until this point; instead, he looked like a chief revenue officer. Hiring an external candidate to help bring monetization into the app was a culture shift for Duolingo, which had previously simply hired off of its mission. Nevertheless, Meese’s gaming experience complemented Duolingo’s natural gravitation toward gamification, and he had only one job: unearth new revenue streams.

Meese immediately brought his attention to in-app purchases, with the goal of keeping the guardrails of engagement and retention in focus. Similar to advertising, in-app purchases are common revenue generators in free-to-play games, with mobile gamers spending an average of $87 a year on the hooks. In mobile games, people tend to pay money to progress faster, whether it’s buying an extra life or buying ammo that would help them beat a villain they otherwise couldn’t.

It was an obvious approach to fix the company’s finances, but there was one problem: Von Ahn didn’t like the model because it required people to pay to learn faster, which seemed directly at odds with the company’s mission. At yet another dead end, Meese turned to the most obvious monetization route of them all: subscriptions.

Maybe you couldn’t pay to learn, but what if you could pay to save time?

Duolingo Plus gold

If not for Duolingo’s allergy to monetization, subscription would have been the first and obvious revenue model right from the company’s founding. The company had spent half a decade getting millions of users emotionally engaged with its app — some percentage of users would almost certainly be willing to pay to have a better experience or just buy into its mission. But how should the company do subscription without alienating its core and passionate users?

At that exact moment, there was another app garnering huge attention that offered a potential model. Dating app Tinder launched in 2012 and exploded in popularity with its now ubiquitous left-swipe/right-swipe mechanic. Outside the leaderboard features of Duolingo, the app was mostly single player, but Tinder was a very different beast: It needed massive user scale to drive network effects to dominate the online dating market. Tinder needed a way to give away the core value of its product while building a strong business off of the fraction of users who will pay for elevated services.

A year before monetization became a top priority for Duolingo, Tinder launched its premium product Tinder Plus, which cost $6.99 a month at launch. It offered features like an undo button for errant swipes and a passport option that allowed users to search for love outside of their current geographic region.

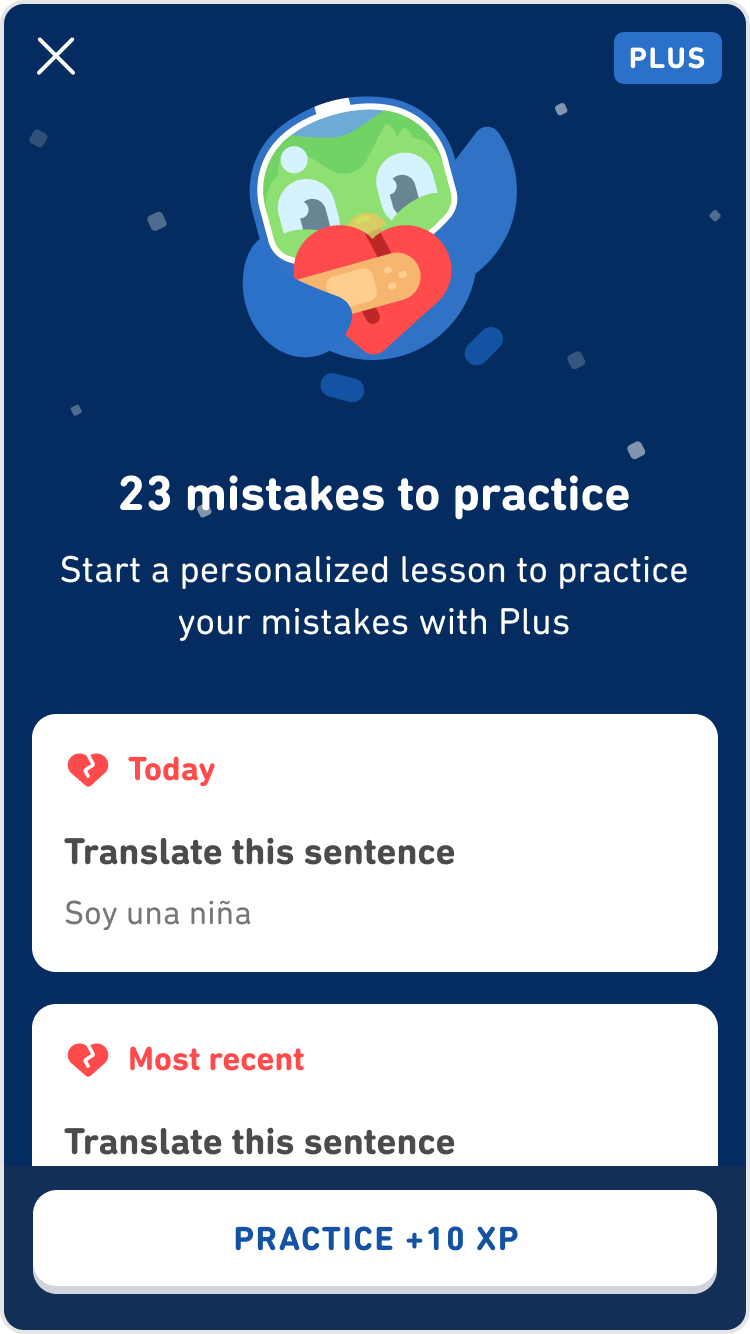

Duolingo would end up piggybacking off of Tinder’s branding, launching Duolingo Plus at the same price point. Months after von Ahn wrote his first blog post about monetization at Duolingo, he announced the new premium service, which was rolled out first on Android. The monthly subscription option offered the ability to remove advertisements as well as download lessons for offline use. Eventually, Duolingo Plus included a monthly streak repair, unlimited hearts, skill test-outs, and a progress and mastery quiz. Users were offered a 14-day free trial before subscribing.

Subscription growth has been staggering since its launch, with a majority of Duolingo’s revenues coming from its subscription product. It currently has 1.5 million premium subscribers, or 4% of all active users, which is up from 3% less than a year ago as pandemic ennui led to a boost in language-learning demand.

The Duolingo Plus dashboard. Image Credits: Duolingo

Charging forth, but not for education

Duolingo was finally evolving from a scrappy startup into a bona fide business. It hired Cammie Dunaway, a former CMO at Yahoo and Nintendo, as its chief marketing officer. She was charged with explaining Duolingo’s mission to a global audience and launching its first global campaign.

“The last thing I have an interest in is trying to market a crappy product with good ads,” Dunaway said. “But to be able to take this outstanding product and beautiful design and a mascot like Duo who already had a hardcore fan base, and just trying to build even more awareness of that and bring even more people in to the experience is, as I said, it’s just kind of a marketing dream.”

One challenge for Duolingo is carving out a persona for its paid subscribers. Unlike its inspiration Tinder, the product is used by a huge spectrum of people, from eight-year-olds to 90-somethings. Despite the breadth of users, the majority of Duolingo’s paid subscribers on average skew 35 and older, and come from the United States and United Kingdom. Interestingly, the motivation for subscribers tends to be more around travel or culture as opposed to schooling.

In most freemium businesses, a majority of users are able to use a service for free because of the money that a minority of users pay for an elevated experience. Molly Lindsay, vice president of strategy and business operations, said that she thinks Duolingo differentiates itself from other freemium businesses in what it chooses to elevate.

“Obviously, the sort of predominant subscription model for learning-focused products is you charge for the learning content, because that is most of the value of the thing,” she said. “And so that’s the sort of core contrary and choice that we made early on and that we have stuck with.”

Duolingo went from a company that refused to charge users, to a company that refused to charge users for access to educational material. “If you’re in a wealthy country and you have an iPhone 11 and you use Duolingo a lot, I don’t feel bad charging you,” von Ahn told TechCrunch in September. “But if you have a low-end device in India, I don’t particularly want to charge you.”

Personalized lessons offer speedier education with Duolingo Plus. Image Credits: Duolingo

Beyond subscriptions, Duolingo’s massive user base isn’t going unused. The startup’s second-biggest source of revenue is advertisements, and while it’s a shrinking portion of revenue, CFO Matt Skaruppa doesn’t expect it to ever leave the experience. Users also provide free marketing for Duolingo by sharing the app and their progress with friends and meme-ing it, which is Duolingo’s biggest channel of user acquisition from launch to today. The Duolingo English Test, which von Ahn hoped would account for 20% of its revenue in 2019, has been growing rapidly since the pandemic forced universities to accept virtual tests.

“Even four years ago, we’d be happy if we made $20 million a year,” said von Ahn. “We’ve now surpassed that by a wide margin.”

Bookings for Duolingo hit $190 million in 2020, the majority of which was closed in the first half of that year. This total is up from $88 million the year prior and $36 million in 2018. The company offered bookings, the total value of subscriptions signed in a period of time, as a proxy for revenue, which is what gets accounted for when the service is actually executed.

Image Credits: Duolingo

Duobingo

While Duolingo’s late monetization has been successful from a balance-sheet perspective, it is still a sensitive topic. Unlike perhaps the typical startup CEO, von Ahn actually still spends energy limiting monetization. “One of the biggest reassurances is that Luis himself is one of the biggest pushbacks when it comes to adding more monetization features,” said Tsai.

Duolingo team dinner in 2013. Image Credits: Duolingo

“I grew up in a poor country and Severin grew up in a rich country. I sometimes think he’s just more like, ‘What’s the problem with charging people for this?’” von Ahn said. “He wants to do the long-term thing. He’s a lot more okay with charging, which is, you know, not necessarily a bad thing, it’s a healthy tension.”

After struggling to monetize for years, Duolingo and its final business model still ended up going the subscription route used by most of its competitors today, such as Busuu and Babbel. Its difference, with a nod to its mission, is that it doesn’t charge for content, unlike its peers.

While it doesn’t touch learning content, no one can claim that monetization doesn’t touch the value of the learning content. In other words, you can’t pay to learn more, but you can pay to learn in a way that is easier to focus on and might have better outcomes. Subscribers are over four times more likely to finish the Spanish course than non-Duolingo Plus subscribers, the app’s monetization page says.

“A lot of [debates internally] are about our subscription page,” said Tyler Murphy, chief designer at Duolingo. “It’s probably the screen of the app that we are changing and testing the most.”

This is an asterisk that has grown in intensity over time for Duolingo. The semantics that would allow Duolingo to introduce subscriptions are the ones that have also put it on a feared slippery slope. That’s the key tension for what the future holds as the company continues scaling, the subject of our fourth and final part of this EC-1.

Duolingo EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product-led growth strategy

- Part 3: Monetization

- Part 4: New initiatives and future outlook

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.