As investing whirlwind Chamath Palihapitiya continues to make headlines with his full-court press to take private tech companies public via SPACs while markets are hot, one of his targets has disclosed financial information that helps us better understand the transaction it is undertaking.

Palihapitiya’s Social Capital Hedosophia Holdings Corp. II (a public, blank-check company, or SPAC) is combining with Opendoor, a San Francisco-based tech startup that facilitates real estate transactions. Opendoor often buys homes from sellers, later selling them itself. Given the complexity present in the residential real estate market and its scale, the company is an interesting play.

TechCrunch covered the Opendoor-SPAC tie-up in mid-September, when it was announced. Yesterday we got a fuller look into Opendoor’s financial results. So, this morning, let’s peek at the numbers to see if we can spy what Palihapitiya talked about in his investment thesis concerning the company’s future prospects.

The results

Opendoor’s 2020 results are not stellar. But that fact is not a surprise. The company went through a round of layoffs in April, impacting around 35% of its staff at the time.

However, even then, TechCrunch reported that “home sales haven’t fallen as far or as fast as one might imagine.” Indeed, in many markets the real estate market has proved surprisingly durable during the COVID lockdowns as some leave major cities for smaller municipalities.

Opendoor says plainly in its SEC filing concerning its combination with the SPAC that COVID has “adversely affected our business.” Its results, then, are framed by a changing market and a pandemic, even if areas of residential real estate have held up better than we might have anticipated.

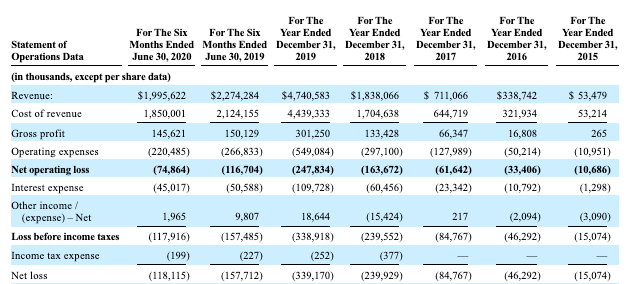

Here are Opendoor’s raw numbers, for your perusal:

You have to read right-to-left to follow the flow of time correctly.

What you can quickly see is a high-growth company with a history of sharp net losses. Opendoor grew from $53.5 million in 2015 revenue to $338.7 million in 2016. That became $711.1 million in 2017, and $1.84 billion in 2018. By 2019, Opendoor was able to drive $4.74 billion in total revenue, $2.27 billion of the total sum in the first half of the year.

And, then, in the first half of 2020, revenue dipped to $2.0 billion, its first reported decline. At the same time, the company’s net loss dipped, a sign that could indicate a healthier company in financial terms. Opendoor’s slim 7.3% gross margins in H1 2020 however, underscore that the company is no software firm and that we can’t compare its revenue and revenue growth to higher-margin entities that feature recurring incomes.

With growth slowing to negative levels and slim margins, what about Opendoor is so attractive to Palihapitiya and his partners in the deal? Here’s the company’s argument in three slides from its early investor presentation.

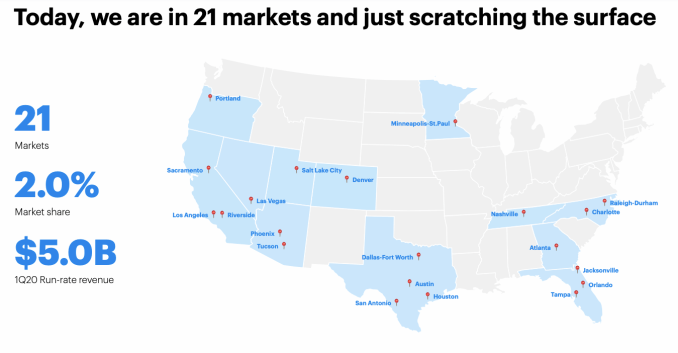

Slide one, showing the company’s footprint today:

And, in slide two of our excerpted three, where the company thinks its can get to with its current strategy:

Please note that Providence, my adopted home town, made the cut.

But wait! There’s more in slide three, which makes the argument that even if Opendoor managed what we saw in slide two, it would have plenty of market left to sell into:

That’s the bullish story.

If you imagine the revenue gains that slides two and three indicate could happen, mixing in some improved economics for Opendoor at scale, and, voilà, the company is worth a zillion dollars. That makes its current SPAC-led public debut cheap at half the price. This is especially true if the company can enjoy operating leverage over time; do its engineering costs, say, decline a percent of revenue as its top line expands?

Palihapitiya is certainly bullish, arguing in his investment thesis that Opendoor could effectively double its 2019 revenue result of $4.7 billion in 2023, reaching top line of $9.8 billion that year.

Let’s see.