Funding comes in stages.

Understanding these will help you know when and where to go for funding at each stage of your business. Further, it will help you communicate with funders more precisely. What you think when you hear “seed funding” and “A rounds” might be different from what investors think. You both need to be on the same page as you move forward.

Early money stage

The first stage is early money, when cash is invested in exchange for large amounts of equity. This cash, which ranges between $1,000 and $500,000, typically, comes from the three Fs: friends, family and (we don’t like this nomenclature) fools. The last-named folks are essentially “giving” you cash, and these investors are well-aware that you will most likely fail — hence, “fools.”

Your earliest investors should reap the biggest rewards because they are taking the most risk. The assumption is that, ultimately, you’ll make good or improve their investment. The reality, they understand, is that you probably won’t.

Your first money may come from bootstrapping or F&F, and your first big checks may come from an accelerator that pays you about $50,000 for a fairly large stake in your company. Accelerators are essentially greenhouses — or incubators — for startups. You apply to them. If accepted, you get assistance and a small amount of funding.

Why do investors give early money? Because they trust you, they understand your industry and they believe you can succeed. Some are curious about what you are doing and want to be close to the action. Others want to lock you up in case you are successful. In fact, many accelerators have this in mind when they connect with new startups. At its core, the funding landscape is surprisingly narrow. When you begin fundraising, you’ll hear a lot of terminology including descriptions of various funding categories and investors. Let’s talk about them one by one.

Bootstrapping

As the old saying goes, if you need a helping hand, you’ll find it at the end of your arm. With that adage in mind, let’s begin with bootstrapping.

Bootstrapping comes from the concept of “pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps,” a comical image that computer scientists adapted to describe how a computer starts from a powered-down state. In the case of an entrepreneur, bootstrapping is synonymous with sweat equity — your own work and money that you put into your business without outside help.

Bootstrapping is often the only way to begin a business as an entrepreneur. By bootstrapping, you will find out very quickly how invested you are, personally, in your idea.

Bootstrapping requires you to spend money or resources on yourself. This means you either spend your own cash to build an early version of your product, or you build the product yourself, using your own skills and experience. In the case of service businesses — IT shops, design houses and so on — it requires you to quit your day job and invest, full time, in your own business.

Bootstrapping should be a finite action. For example, you should plan to bootstrap for a year or less and plan to spend a certain amount of money bootstrapping. If you blow past your time or money budget with little to show for your efforts, you should probably scrap the idea.

Some ideas take very little cash to bootstrap. These businesses require sweat equity — that is, your own work on a project that leads to at least a minimum viable product (MVP).

Consider an entrepreneur who wants to build a new app-based business in which users pay (or will pay) for access to a service. Very basic Apple iOS and Google Android applications cost about $25,000 to build, and they can take up to six months to design and implement. You could also create a simpler, web-based version of the application as a bootstrapping effort, which often takes far less cash — about $5,000 at $50 an hour.

You can also teach yourself to code and build your MVP yourself. This is often how tech businesses begin, and it says plenty about the need for founders to code or at least be proficient in the technical aspects of their business.

You can’t bootstrap forever. One entrepreneur we encountered was building a dating app. She had dedicated her life to this dating app, spending all of her money, quitting her job to continue to build it. She slept on couches and told everyone she knew about the app, networking to within an inch of her life. Years later it is a dead app in an app store containing millions of dead apps. While this behavior might get results one in a thousand times, few entrepreneurs can survive for a year of app-induced penury, let alone multiple years.

Another entrepreneur we knew was focused on nanotubes. He spent years rushing here and there, wasting cash on flights and taking meetings with people who wanted to sell him services. Many smart investors told him that he should go and work internally at a nanotube business and then branch out when he was ready. Instead, he attacked all angles for years, eventually leading to exhaustion. He’s still at it, however, which is a testament to his intensity.

Both of these entrepreneurs should have been ready to cut and run after two years of backward momentum. Ideas, even ideas that exist in reality, are worthless unless they bring in money. These entrepreneurs bootstrapped for far too long.

We’ve seen all types of founders, and we’ve bootstrapped plenty of failed ideas. Trust us: Don’t waste valuable time chasing a dead product. Before you bootstrap, write down your one- and two-year goals.

Say you want to make enough to hire a single programmer in Year One to help build the app. Then your business must make at least $100,000. Then, in two years, assume you will be working full time on the app. Expect the app to be making $300,000 or so, depending on your current salary. Anything under these targets is reason to quit.

Again, these numbers are potentially alarming but also realistic. Realism is the antidote to many of the poisons of passionate entrepreneurship — namely, self-delusions.

Bootstrapping is not a suicide pact. By setting a time limit and budgeting for your bootstrapping effort, you can prevent burnout, starvation and failure. And you will fail if you don’t set limits.

Bootstrapping is far harder with brick-and-mortar businesses, but at least with those you can see, feel and even visit your vision. In the documentary “42 Grams,” the restaurateur Jake Bickelhaupt spent years running a small dinner club out of his living room before opening what became a well-known and much-lauded restaurant of his own. He started small — he dedicated every inch of his apartment to the dinner club — and grew from there. Start small and grow big is the bootstrapper’s credo.

Bickelhaupt later closed his restaurant. Sometimes even passion can’t sustain you against the outrages of fate.

Bootstrapping in the Danger Zone

How can you hack the bootstrapping process? One of the most obvious — and most dangerous — methods, popularized by Brian Chesky of Airbnb, involves credit cards. Lots of credit cards.

In a frequently retold tale, Chesky paid for many of Airbnb’s early bills with credit cards he kept in a baseball card storage folder. Author Cole Schafer wrote:

Brian Chesky and the lost boys (his co-founders) stumbled upon the idea of Airbnb after finding themselves unable to pay rent on their pricey San Francisco apartment.

They did what most sane individuals strapped for cash would do — blew up three air mattresses in a spare bedroom, served breakfast, and rented them out to complete strangers.

Hence the name, Airbed & Breakfast (Airbnb).

Well, to everyone’s surprise, three guests showed up, shelled out $80 apiece and boom-shocka-locka! Brian and the lost boys had their rent money and didn’t have to live in a box on the street.

Fast-forward several months and the overzealous entrepreneurs found themselves $20,000 in debt — they literally filled a binder with dozens of credit cards and maxed them out to build the beginnings of Airbnb.

In order to pay off this debt, Chesky and his partners, who were trained as designers at the Rhode Island School of Design and other prestigious specialty schools, created cereal boxes — Obama O’s and Cap’ McCain’s — and sold them online. They made $30,000 after expenses, allowing the company to live to fight another day.

You’ll note that while they did spend their own money, in the form of debt, they were able to get what amounted to a very expensive loan. Further, rather than pour more cash into a business that was nearly failing, they used their other talents to crack the debt into pieces.

That’s right: One of the biggest startups in the world survived not by doing what they built it to do but because they sold some generic cereal. Chesky himself credits this move with getting them a spot in the well-known accelerator Y Combinator, simply because their product was unique.

This story teaches us a few things about bootstrapping:

- When your business works — that is, when it gets its first few customers — you should consider your bootstrapping efforts a success and invest more of your own time and cash into the business. Throwing good money after bad results, however, is never the right move. Chesky’s case is unique in that he repaid his debts with an ancillary product related to his skills.

- Credit cards, home equity loans, and personal loans are a dangerous trap for many entrepreneurs, and you should use them with care to fund your business. Chesky and his friends saw that the idea had legs; they just didn’t know what to do to make it work. The credit cards bought them a few months to explore. They were also in Silicon Valley, the capital of cheap capital. Even if they ran up credit cards, they had an opportunity to pay them off with a single check. This is rarely the case when it comes to situations or places less conducive to fast investment.

- Be ready to make money any way you can. Chesky and his friends were designers, not coders, so they used their skills to make physical products to make a product that they could sell. Too many entrepreneurs say, “I quit my job and won’t do anything else in order to build my startup.” That’s a recipe for disaster. The startup needs cash to survive, as do you. You must do everything in your power to ensure that cash keeps coming in. A regular infusion of cash defines a business. You need that cash to grow your idea. You need to keep working for pay, not just subsisting off of the fumes of entrepreneurial passion.

Without a steady source of income, your company lives on borrowed time. When what little money you bring in comes directly from your pocket, the appreciation of your predicament becomes even clearer. Therefore, you should be ready to pull the plug if you discover that the bootstrapping isn’t working.

What about companies like Amazon and Tesla? Amazon didn’t make a profit immediately, and Tesla may never reach that point. These companies are unique in that they received and continue to receive massive influxes of cash from their founders and then even bigger influxes from investors. They would not have survived long on bootstrapping alone.

As a bootstrapper, you should be well-aware of how much money you have and how much you and your co-founders will invest in the idea. One of the benefits of going all-in is the clarity of purpose it engenders. If you put everything on the line — your job, your house, your ability to feed yourself — you definitely will feel encouraged to build your business. Some of us need this kind of push to succeed. But don’t be foolish with your time, your prospects and your cash. If it doesn’t make sense in year one, it definitely won’t make sense in year five, and, by that time, your opportunity costs will be huge.

While difficult, bootstrapping is not impossible. In fact, it’s the method we recommend first when it comes to building a business.

The takeaway here is simple: Create a document that describes your intended burn rate, and stick to it. One entrepreneur I spoke to in D.C. gave himself a year to break even on his business and gave himself the same deal over and over again — for 20 years. He agreed with his wife that he would quit the instant the business cost more to run than it made, and he has been pleasantly surprised for two decades.

We recommend writing out a simple business plan like the one in Table 3.1 with all of the expected costs laid out per month. As you can see from the table, we’ve assumed very basic costs and fairly ambitious projected income after launch. Most of the things are regular, repeating costs including hosting and accounting software, and if you are building an app, you will need a great deal of marketing, even before launch. The result? You’re bootstrapping a money-losing business by the end of the year, especially if your income projections are incorrect.

Friends and family rounds

Perhaps you’ve bootstrapped and succeeded. Perhaps your business is taking off, but it needs an afterburner to take it out of the stratosphere. What can you do next?

“I’ve met many investors, but in the end it’s friends and family who helped me get back on my feet again after losing almost everything,” said one founder we talked to during our research.

You turn to people who know you and trust you. One of the most common funding strategies early startups use to get off the ground is friends and family (F&F) funding.

You may be thinking that getting a few hundred dollars from a friend or family member to start a business isn’t going to be enough, but take a moment and consider these examples:

- J. A. Albertson borrowed $7,500 from his wife’s aunt to help co-found Albertsons grocery stores.

- Brothers Dan and Frank Carney borrowed $600 from their mother and opened a pizza restaurant called Pizza Hut. When they sold their business for $300 million to PepsiCo in 1977, Pizza Hut had over 4,000 locations.

- In more recent history, Steven Yang, a former senior engineer at Google, borrowed $400,000 from his mom to start Anker. Today, Anker is the world’s most popular mobile charging brand with over $1 billion in annual revenue. [Author Eric Villines is head of PR at Anker.]

Before going down this funding path, however, you need to understand that borrowing money from friends and family could mean lost friendships and strained relationships with relatives. Be honest with your friends and family about the inherent risks of investing in a startup and tell them that there is a very real chance your business — along with 90% of startups — will fail. Be careful, and make sure you take money only from people who can afford to lose it. There are several ways you can structure friends and family funding, each with its own pros and cons, as well as tax and legal implications.

Cash gifts

You may have people in your life who want to help sponsor your business simply because they want to support you. In this scenario, and based on the 2019 IRS tax code, they could provide you with a one- time, tax-free gift of up to $15,000 in a calendar year. They could of course give more, but both you and that individual might be required to pay taxes on that money.

Before going down this path, seek the advice of a professional accountant or tax attorney.

Loans

Of all the friends and family funding options, this is the one you really need to think through. That is because regardless of whether your business succeeds or fails, you will still need to pay back the loan. A loan with structured monthly payments can be a great way to make friends and family feel more comfortable about helping you fund your business.

You can find a personal loan agreement online easily enough, but we suggest getting your funder to agree to a third-party loan management service such as Loan Back (loanback.com) or Zimple Money (zimplemoney.com). These services will not only provide all the legal paperwork but will also act as an intermediary to collect monthly payments. Positioning this proactively to someone who might be willing to loan you money could go a long way.

The key factors you must assess with your investor before borrowing money are these:

- Amount: As with any loan, you need to ensure that you pay back the loan, especially if your business is in very early stages and isn’t making income.

- Interest rate: This may not be applicable, but when borrowing money from friends or family members, particularly if they are taking money out from their own investments, it would be a good idea to add an interest rate to help offset the costs of lending you the money.

- Repayment terms: This isn’t going to be a traditional bank loan, so you decide on the terms. It could be monthly payments over a period of months or years or a lump-sum payback on a specific date.

- Contingencies: There is no telling where your idea will end up and you may go bankrupt. You should probably work with your friends and family to create a payment plan that will reflect this. Some angels will forgive your debt; others will hold it over you like the sword of Damocles.

F&F equity investment

If you have friends or family members willing to provide a significant cash investment (more than $10,000), and you feel comfortable giving them an ownership stake in your company, then this might be a good option to secure financing. Unlike a loan, you do not have to pay back this money until you make a profit or sell the company. However, there are valuation and legal implications you must consider before going down this path:

- Valuation: Investors, whether friends and family members or angels, are giving you money for shares in your business. At the friends and family stage, you should be creating a smaller valuation of between $250,000 to $1 million. This means in later stages, as you target outside investments from angels and others, you will have room to increase the valuation and make your business an attractive investment.

- Securities: This may be surprising, but if you are promoting an investment opportunity — even to family members — this activity is regulated by both state and federal agencies. When it comes to smaller friends and family investments, there are a number of exemptions that should make things easier, but you do not want to violate securities law. We strongly suggest seeking out legal advice before accepting any investment funds.

- Investors’ role: One of the most frustrating things for many founders is getting unsolicited advice. This will be especially true from people who give you money. You need to make sure everyone is clear on what their role will be. Will they be part of the management team? Will they be silent partners? Clarifying this up front will go a long way in keeping the drama to a minimum later on.

Friends and family (F&F) rounds are often the first money an entrepreneur will take after building an MVP and making a small amount of revenue. What if you just have a good idea? Then you’d better have some good friends. Unless you are making cash or your idea is a sure thing — that is, you are on the cusp of a massive technological or societal breakthrough — then expect to be turned down again and again for F&F rounds until you are able to make money.

Crowdfunding and F&F

At the F&F stage, we often find that founders like to try techniques like crowdfunding or donations to raise cash. John and Molly Chester wanted to create a farm where they could grow pesticide-free delicious foods. In 2011 they found a plot of overworked land and created a simple presentation they showed to friends and family, and they also crowdfunded online. The resulting influx of cash allowed them to buy the farm and begin their mission. Now the farm is world famous, and their biodynamic methods were outlined in the movie “The Biggest Little Farm.” In short, the Chesters realized they wouldn’t be able to raise enough money from F&F alone so they cast their net wider to grab more “fools” who loved delicious food.

Angel investment

Angel investors are people who can truly change your life. These investors are independently wealthy and act independently. They have cash to spend on investments, and if you find these investors, we encourage you to consider them as good as gold. They are, in short, the people who write big checks when the risks are high and your chances of success are low.

Angels come in many forms. Some are friends or family, and others are co-workers who made it big and are now trying to pay it forward. Many cities have angel groups that meet once a month to hear about new deals. These groups are made up of wealthy individuals who both feel that they can give back to their community through investment and can probably make a little cash in the process.

Angel investors will often ask for decidedly unique terms on their investment. For example, we’ve seen some deals that culminated in an investor owning half a company for about $100,000 in cash. These deals are predatory and often the last resort for founders who have tried everything else. If you fall into one of these deals, you’re stuck. For this reason, some angel rounds can actually damage a startup before it begins.

That said, good angels are a treasure. These folks will give you the runway you need to win, and if you fall into trouble, they’ll be there when you need them. A good angel is just that — an angel.

Angel money usually comes before an actual product has left the workshop. You use this cash to build the prototype necessary to take to investors or, say, fund a pop-up shop to test your product in the wild. One thing to consider is what kinds of businesses will receive early money and what won’t. Apps and web services typically don’t receive angel money. At this point, investors don’t see the benefit of giving cash to support the idea of an app before that app has proven itself. You can easily get a web app built for under $10,000 and try to spread the word with another $5,000 in marketing money. Most founders bootstrap.

Angel money is rare. When you access it, cherish it. Don’t expect it to arrive when you need it. It will be there for you only when effort, interest and excitement come together in the head of a person with money.

Seed stage

The next stage, the seed stage, comes when a product is developed or launched. This money comes when you’ve proven that the world wants your product and is willing to pay for it. Many startups can’t even get to this point.

Many entrepreneurs believe that seed funding is for untested ideas. After all, the idea of a seed is simple: You don’t know what will grow until you give it resources. Unfortunately, most investors want to see the seed sprouting and even bearing fruit before they’ll sign a check.

Seed investors are looking for monthly recurring revenue, a solid team and active users. Again, there are exceptions to this rule, but expect to talk to seed investors when you have cash in the bank. Interestingly, many startups avoid seed funding entirely because the little cash coming in from actual customers helps offset the cost of operation.

How should you understand the seed stage investors? Assume they are looking for a real return on investment.

There’s a very important scene in the Coen brothers’ movie “Inside Llewyn Davis.” The star of the movie, a folk singer in 1960s New York, goes to a club in Chicago in hopes of getting a gig. He plays a heartfelt rendition of “The Death of Queen Jane,” a beautiful song that Davis pours his heart into. The club owner listens and then shrugs.

“I don’t see a lot of money here,” he says.

Seed investors expect their investments to grow by some multiple, and they are placing money into a company to help it grow, not build it outright. Seed investors expect a minimum viable product before they will consider investing, and many even expect some kind of revenue, a horrible catch-22 for most founders. After all, if you have revenue, you are probably past the point where seed funding is necessary.

The seed stage is the point when most startups fail. Having and building a great idea is just the start, and you begin falling prey to various traps as you begin expanding. Without a solid infusion of cash at this point, you are almost always doomed. You should begin seed fundraising as soon as you start gathering revenue and have a clear explanation for why you need the cash at this stage. Better yet, we recommend working hard to raise revenue and even profit at this stage in order to avoid raising capital entirely. The choice, however, is yours.

At the seed stage your company raises money to grow and then enters the next stage.

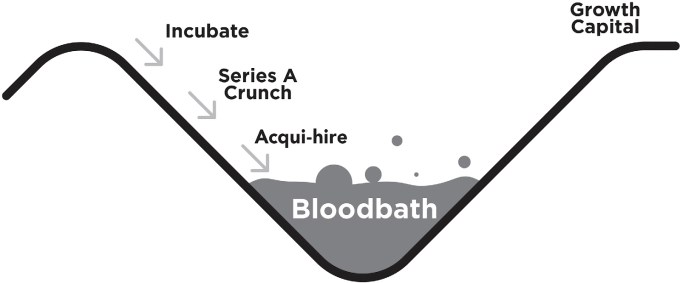

Startup Valley of Death

As you move through fundraising, you will find yourself in dire straits many times. But there is one situation that could shut you down sooner than you expect. Say you’ve raised a small round from friends and angels. You can even raise millions. You can have solid revenue. You can be successful on paper. But every business can exist just long enough to fail. This point of failure is what investor Keith Teare called the “Startup Valley of Death.” Every founder in every industry will face it. We want you to be ready.

The Valley of Death can occur at any time between launch and true growth, but it usually happens after you’ve built your product and have had some success selling it. In many cases, entrepreneurs raise enough to fail. Teare uses the table shown below in his presentations, and we think it’s sufficiently frightening to recreate here.

| Jan. | Feb. | March | April | May | June | ||

| Hosting |

$60 |

$60 |

$60 |

$60 |

$60 |

$60 |

|

| Development |

3,000 |

3,000 |

3,000 |

3,000 |

3,000 |

100 |

|

| Marketing |

500 |

500 |

500 |

500 |

500 |

500 |

|

| Accounting Software |

69.99 |

69.99 |

69.99 |

69.99 |

69.99 |

69.99 |

|

| Insurance |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

3,730 |

3,730 |

3,730 |

3,730 |

3,730 |

830 |

||

| Projected Income |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$100 |

|

What’s worse is that the current fashionable startup model encourages this. Because founders are told to build a minimum viable product and then test for product-to-market fit, they often spend thousands on a preliminary product that isn’t ready to scale outside of their very specific use cases.

Product-to-market fit is, quite simply, a found need in a market for your product. The product-to-market fit of cream is easy — people who like coffee love it, and you can sell it if you make it. The product-to-market fit of an asteroid-mining company is far harder to find. This requires vision and courage. And it requires asteroids to contain something that the general market wants.

If you have product-to-market fit, then you will start moving slowly into the valley of death. Here’s what to expect.

The first part of the Valley of Death, the approach, involves all the feel-good aspects of founding a company. You and your core team begin to incubate the idea, and you work toward further funding. Each step is a joy because it looks like you’re moving forward. In reality, though, you’re on borrowed time.

Then comes the valley. In this period, the founding team might split up, an investor might try to buy out the idea and your equity is diluted beyond recognition. Because of the earlier investments you’ve raised, you can’t raise any more. You’ve raised so much that your current investors don’t want to put any more in. It is at this stage you can realistically lose your business through a sale — also called an “acqui-hire” — because it’s the only way forward. You could also face a shutdown even if revenues are strong.

One company, Zirtual, faced this valley at the height of its success. The founder, Maren Kate, wrote a fascinating description of the experience on a public Medium post. In short, the company burned through more money than it could make:

Burn is that tricky thing that isn’t discussed much in the Silicon Valley community because access to capital, in good times, seems so easy. Burn is the amount of money that goes out the door, over and above what comes in, so if you earn $100 in a month but pay out $150, your burn is $50. Zirtual was not flush with capital — for as many people as we had, we were extremely lean. In total we raised almost $5 million over the past three years, but when we moved from independent contractors (ICs) to employees, our costs skyrocketed. (Simple math is add 20% to 30% on to whatever you pay an IC to know what it will cost to have them as an employee.)

And at the end of the day, “burn” is what happened to Zirtual.

The reason we couldn’t give more notice was that up until the eleventh hour, I did everything I could to raise more money and right the ship.

After failing to secure more funds, the law required us to terminate everyone when it became clear to us that we wouldn’t be able to make the next payroll.

An outside company bought Zirtual’s assets and started it back up. By reformulating the product and changing the business model — something that could be done only when the company was completely shut down — they were able to escape the valley and continue to grow.

The Startup Valley of Death means different things to different startups. To Zirtual it meant a discount sale and a relaunch. To Freemit, a startup I (John) founded, it meant bankruptcy. To many others it means turning into a ghost of a company without customers or a product. In the end, it takes a very skilled or lucky founder to escape the valley.

There are exceptions to this model, of course. But it’s best to assume that you’re not one of them. Amazon didn’t turn a profit for decades while Uber and Lyft, two startup darlings, have been burning cash like coal. No one would claim that those companies should have been shut down. Instead, they negotiated the Valley of Death and made it to the growth capital stage, a lovely position for any founder to be in.

Growth stage

So, you’ve survived the Startup Valley of Death. Good job. Now the real fun starts.

After you’ve built your business and it is running comfortably, you will enter the growth stage. This stage involves raising money to do very specific things in order to achieve the following:

- Be interesting to buyers.

- Expand your customer base.

- Hire to make more money.

- Expand geographically.

- Expand your technology.

This capital gets you from profitability — or revenue — to an initial public offering (IPO) or a sale, and these investors expect returns in multiples of 10 times their initial contribution. Growth capital providers are looking for a big payoff from a solid idea. This capital comes in tranches — Series A, Series B, Series C and so on — and investors chip away at parts of the company by taking more and more equity. A company that passes through this stage and receives growth capital is usually safe for the foreseeable future.

Unfortunately, many companies come out of growth stage very differently from what they looked like when they went in. Many growth stage companies have lost some of the founders along the way. The people who started the business — the team of dreamers who turned an idea into reality — are often cast aside as the company grows and changes. What happens in the growth stage? One founder who built his first 3D printer by hand in a Brooklyn workshop described a strange scene to us a few years ago.

After raising millions of dollars and hiring hundreds of people to build, sell, advertise and support his product, he looked around the office and found that everyone knew him, but he knew none of his employees. He had been so removed from the day-to-day operations of his company that it was now full of strangers. For many, this situation is a dream come true. For others, it is a nightmare.

There are also various other stages including bridge raises — raises in which you gather more cash at a similar valuation as before — in which the valuation does not increase. Further, you can experience a down round in which you raise at a lower valuation in order to attract investors. Entering into deals in which the valuation falls or remains the same is risky and often results in a lack of investor confidence. In other words, try to avoid these stages of venture capital funding if you can.

At this stage you usually approach venture capitalists for help.

Venture capital stage

Venture capital (VC) is what everyone thinks of when they imagine fundraising. Venture capitalists (VCs) are investors who write larger checks for companies in various stages of growth in order to get a large portion of the company early on. Most VCs will offer between $500,000 and a few million dollars, but some will write smaller checks “just to be part of the deal,” as they say. Some won’t get out of bed for less than $10 million.

Nearly anyone can claim to be an investor. Only a few can claim the mantle of venture capitalist. A venture capitalist is, according to Investopedia, “an investor that provides capital to firms exhibiting high growth potential in exchange for an equity stake. This could be funding startup ventures or supporting small companies that wish to expand but do not have access to equities markets.” This means that VCs think like equity investors: If they see a profit and massive returns in a business, they will often write big checks to get access to that potential.

What that means in practice is that by the time you’re ready to enter into a deal with a VC, you’re probably already making money. This never stops beginner entrepreneurs from pitching to countless VCs over and over again long before they are ready. Our advice is to approach VCs only once you have revenue and, potentially, profit.

This does not mean you shouldn’t approach investors for advice. As we mentioned before, the best investors were also operators. They will find the holes in your story faster than anyone. They will also want to hear what you’re working on and follow up when you’re ready for their help. Interestingly, by the time investors are interested in funding you, you often won’t need funding.

Where do you find VCs? You should look for them at industry events like Launch or TechCrunch Disrupt, or, if you’re in Europe, Web Summit. Many of these events have dedicated networking subevents that allow you to come into contact with investors. You will also see investors walking the halls of these events, and there is no reason not to corner them and offer them your two-minute pitch.

Now for the bad news: VCs rarely invest. Many VCs see hundreds or thousands of pitches, but they have room in their portfolios for, at maximum, 10 startups. That means the chance of being picked is tiny. Further, because VCs are interested in solid opportunities that offer massive returns, they often write huge checks in the multimillion-dollar range. It makes perfect sense for investors to say no far more than they will ever say yes.

VCs want a sure thing, or at least a version of a sure thing, they are comfortable supporting. Many VCs style themselves as operations assistants, and they want to believe that the startups they fund will become partners in a multiyear adventure. This is mostly true. However, don’t expect much help from VCs after the check clears unless they consider you completely clueless and are worried about their investment.

This post is an excerpt from “Get Funded!: The Startup Entrepreneur’s Guide to Seriously Successful Fundraising” by John Biggs and Eric Villines, (McGraw Hill, September 8, 2020).