Hello and welcome back to our regular morning look at private companies, public markets and the gray space in between.

It’s been a busy decade in the venture capital world. Ten years ago there were fewer than 20 known unicorns in the United States. That figure has risen to more than 200 in the intervening period. Back in 2010, global venture capital was estimated by some at around $50 billion. Venture reporter and genial chap Jason D. Rowley put that figure at $295 billion, give or take, at the end of 2019.

Hidden in those metrics is not just investment from the venture capital firms most famous in our common mind — Sequoia from the old guard, Andreessen Horowitz from the new. Also included are the efforts of corporate venture capital players. Not as stodgy as they were once considered, corporate venture capital shops (CVCs) have grown in popularity as investment vehicles for cash-rich corporations hoping to avoid being killed off by more vibrant upstarts. The results of that popularity have helped boost rising venture totals.

I’ve spent the last day or so picking through a report1 from industry group Global Corporate Venturing that charts how quickly the CVC world grew in the past decade through the end of 2019. Ahead: how fast CVC has grown, how much capital they are putting to work and what their targets are for investing returns. Understanding how the corporate VC landscape has changed will help us understand how venture itself has changed and how startups should plan their next raise.

CVC growth

If you’ve watched the venture world since the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing global slowdown, you’ve noticed corporate venture players cropping up more and more often in startup dealflow. A good example of this is Microsoft. Redmond once did not have a corporate venture arm. Indeed, the company would tell you quietly at the time that given its extreme wealth balance sheet, venture investing simply wasn’t possibly material to its accounts.

Then, of course, came the Bing Fund, Microsoft Ventures and, today, M12 (which just launched in Europe), Microsoft’s formal venture vehicle that cuts lots of checks. Alphabet, the company previously known as Google back when it had a soul, has several venture arms. Let’s see if you can name them all: GV, formerly Google Ventures, CapitalG and Gradient Ventures. That’s three!

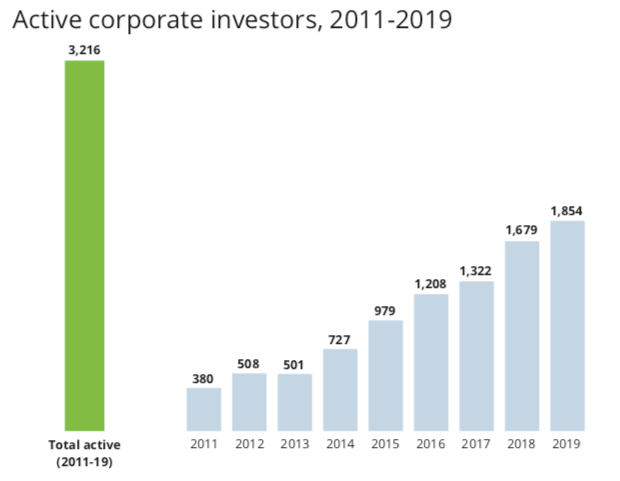

Tech isn’t alone. The report we’re pulling from today has two charts on this trend that caught my eye; here’s the first, which explains itself (charts shared with permission):

This doesn’t go back as far as I’d like, but it paints the trend well: CVC groups have grown by around 5x globally since 2011. That’s the trend you likely already felt in your gut.

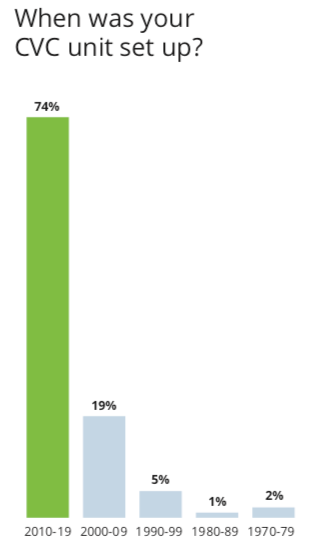

Let’s cut that data a different way. Here’s a related chart, but instead of showing a global, active CVC count by year, it segments the CVC world by age cohort. You can guess what this will look like, given our first chart:

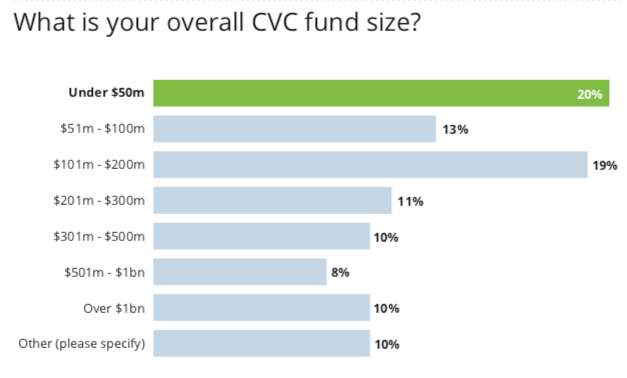

A caveat, however, before we all start to think that CVC could overtake the non-corporate venture world: these funds are mostly pretty small.

That’s not a diss, mind; not every company with its own venture shop is going to have Microsoft or Alphabet’s cash mountain. Indeed, 52% of CVC funds have less than $200 million to put to work — a seed fund today, nearly — and 20% have less than $50 million to play with:

The smaller scale of CVC funds shouldn’t surprise; there aren’t that many companies with more than $200 million to put to work from their balance sheet; the tech world is spoiled to cash-rich companies, a non-reality in many other sectors.

So, there are lots of CVC funds, a somewhat new phenomenon. How active are they?

CVC cadence

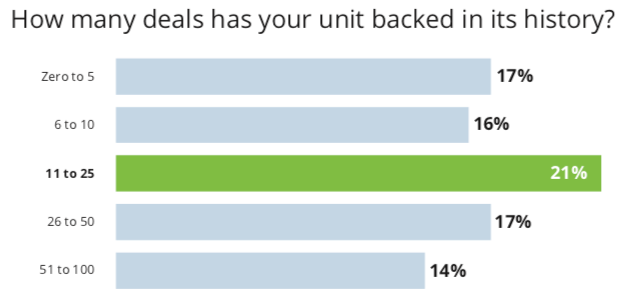

The modern corporate venture fund is more active than I would have thought. Instead of cutting a few checks here and there, only one-third (33%) of CVC players today have made 10 or fewer deals. Going up the activity chart, a fifth (21%) have written 11 to 25 checks and 31% have written even more:

To understand why this chart is interesting, recall how nascent many CVC funds are; that there are so many that have written more than 10 checks given their cohort’s relative youth means that the firms are decently active. I would have guessed a lower level of activity, frankly, if I had made an estimate before peeking through the data.

Not every CVC is Intel Capital, natch, but the category is active despite adding a host of new players in recent years. And what are they shooting to do with all that dealflow? Let’s find out.

CVC goals

Just about two-thirds (65%) of CVC players are tasked with a hybrid goal of both making money and finding strategic opportunities for their parent companies. More simply, big companies want their CVC groups to generate a few bucks while also keeping a deep scan active on companies that could challenge their incumbency.

Just 28% of CVCs only have strategic goals (I wonder if this is the wealthier cut of the CVC market, recalling our Microsoft example from before), while 8% are only in it for the money. Adding two of those figures together, more than 70% of CVC groups have financial goals; they want to generate material returns.

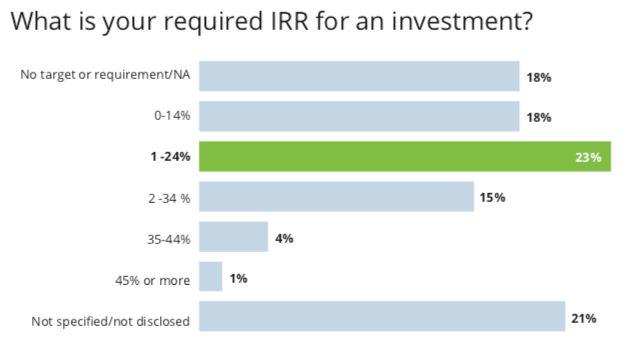

That data point brings us to the following chart, which (with a few typos that we’ll explain shortly) details what sort of internal rate of return (IRR) targets:

Reading this chart both last night and again this morning, I presume that it should read: 0-14%, 14-24%, 24-34% and then 45% or more. That small issue aside, we can see that a portion of CVC firms have no financial targets. That 18% doesn’t precisely track to the 28% of CVC funds that said that they are only interested in strategic returns, but it’s directionally complementary.

What is more interesting is that 64% of CVCs have IRR targets of over 14%. You can dig through Cambridge Associates’ data on venture capital IRR if you’d like, but I think it’s fair to say that 64% of CVCs shooting for 14%+ IRR means that a good chunk are going to miss the mark. That their hopes are higher than their likely results is interesting, as it implies that many CVCs are out there really trying to make a buck.

All told, the rise in the number of CVC players was expected, but I was a little surprised at how active they are, and how financial their goals shook out compared to strategic objectives. You deserve another Americano for getting this far, so go get one.

- Full name: “THE WORLD OF CORPORATE VENTURING 2020 – THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO THE INDUSTRY,” per the document.