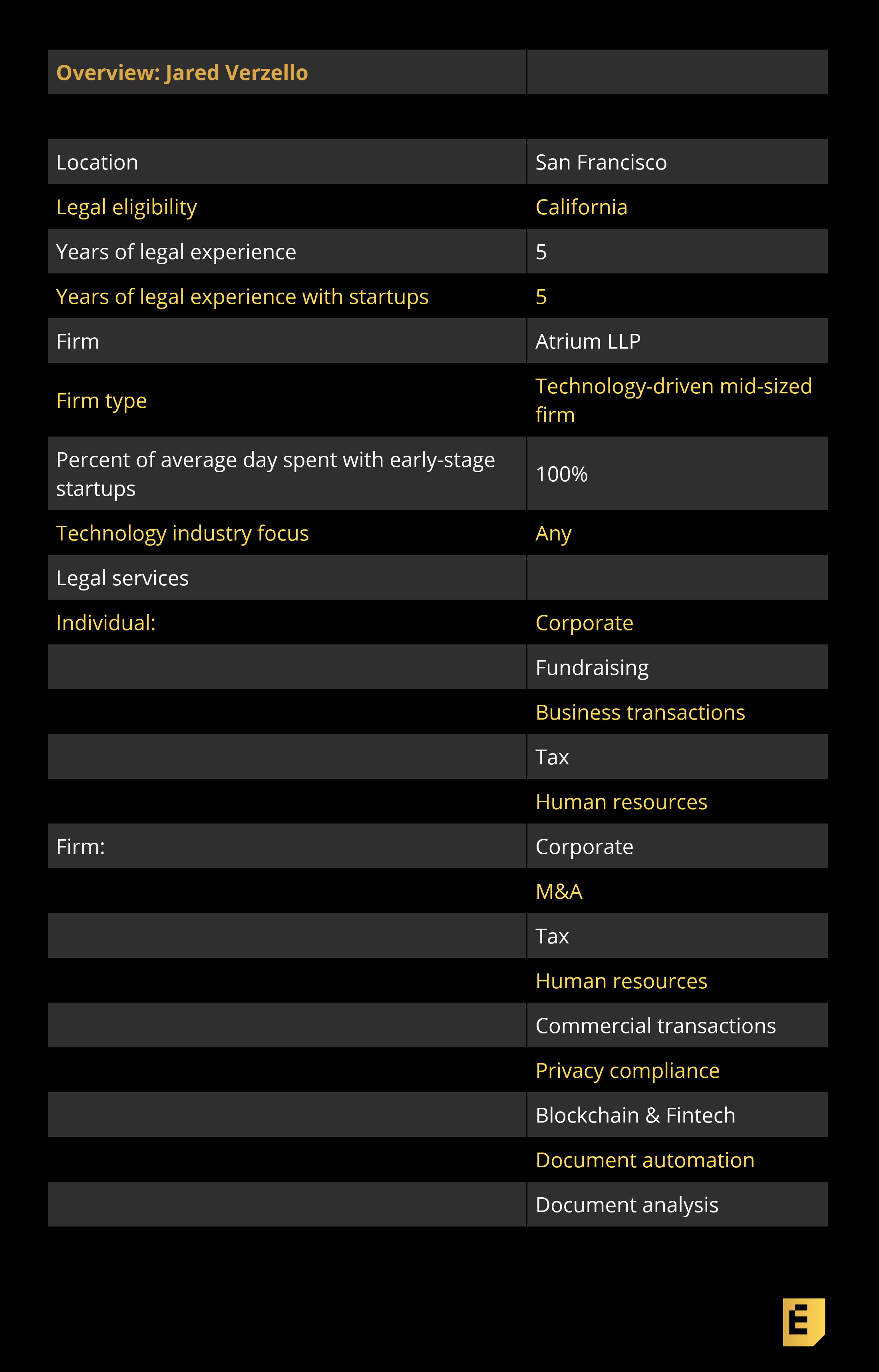

TechCrunch is profiling great startup lawyers wherever they may be working — and that includes within new companies built from the ground up around tech. Today, we’re interviewing Jared Verzello of Atrium. While even the most old-line of law firms have begun integrating document automation and analysis software, Atrium started that way. Around two years old, it’s both a full-service corporate law firm, Atrium LLP, and a technology startup, Atrium Legal Technology Services, that focuses on building tech for its clients and lawyers.

For his part, Verzello joined Atrium 18 months ago from Silicon Valley law firm Cooley LLP, and heads up the seed stage practice. In the interview below, he tells us how he got into this position, how he works with startups from within Atrium, and trends he’s seeing in the market today.

On common founder mistakes:

“Having represented over 20% of Y Combinator (YC) companies for the last few batches, I come across many of the same founder mistakes. One of the more common is that a founder will choose to incorporate as an LLC because they can write off a bit of the losses on their personal tax return.

“As a very early-stage company, one can be exposed to so many vulnerabilities and even potential bullies when it comes to legality. Jared (my attorney) has been knowledgable, understanding, and adaptable and the value of that to a startup cannot be overstated.” Leslie Fong, San Francisco, founder and CEO, VENIM

“But by the time they’ve decided to work with YC, they usually have raised money — often in the form of a convertible note — and they end up having to flip their LLC to a Delaware corporate (YC only invests in Delaware C-corps). What founders don’t realize is there are partnership tax issues for converting with debt outstanding in the business. We end up having to do conversions with $25,000 or $30,000 in legal fees and bring in tax and accounting specialists because a founder got some misguided advice at the very beginning.

“What I advise is that founders should not cut small short-term corners like incorporating as an LLC vs Delaware C-corp if they know they want to be venture-backed.”

On his approach:

“My goal, and Atrium’s goal, is to provide both legal and business advice so that our founders can worry about finding product-market fit or keeping money in the bank versus worrying about legal. My objective is for our clients to be protected but to spend little or no time thinking about legal.

“I always advise my clients that they should not be interested in being innovative in their legal structure. In order for startups to move quickly, the legal should be simple to administer, simple to understand, simple for investors to get on board with, so they can focus all of their brain power into the products and competitive advantage of the business.”

On Atrium:

“When engaging with Atrium, our clients are first and foremost engaging with a law firm but to know if it’s the right fit, I usually try to gauge what type of firm and relationship they want. For example: do you want a firm that’s doing business the same way they’ve always done business, for decades, or do you want a firm that thinks innovatively, like you, and has a key objective to improve their services and operational efficiency over time?”

Below, you’ll find founder recommendations, the full interview, and more details like their pricing and fee structures.

This article is part of our ongoing series covering the early-stage startup lawyers who founders love to work with, based on this survey and our own research — the survey is open indefinitely so please fill it out if you haven’t already. If you’re trying to navigate the early-stage legal landmines, be sure to check out our growing set of in-depth articles, like this checklist of what you need to get done on the corporate side in your first years as a company.

The Interview

Eric Eldon: You’ve ended up in a pretty unique place, in terms of a legal career. Tell me more about how that happened.

Jared Verzello: I’m not a Silicon Valley insider. I’m not from this area. I grew up in Georgia and Connecticut, and I knew nothing about technology companies or any of that stuff when I chose to go to law school. I had an independent reason for going to law school, which is I thought I wanted to do courtroom and trial work, and a lot of the things that you would see lawyers portrayed as in the media, and that’s a whole other can of worms about making long-term education decisions early in life, when you have limited life experience.

Jared Verzello: I’m not a Silicon Valley insider. I’m not from this area. I grew up in Georgia and Connecticut, and I knew nothing about technology companies or any of that stuff when I chose to go to law school. I had an independent reason for going to law school, which is I thought I wanted to do courtroom and trial work, and a lot of the things that you would see lawyers portrayed as in the media, and that’s a whole other can of worms about making long-term education decisions early in life, when you have limited life experience.

But suffice it to say that, once I was in law school, I quickly found out that I was not interested in those more formulaic areas of law. I found them very constraining and not very interesting or creative. Every year students go out and they find the best internships and placement programs that they can get into, they build their resume, as do we all in our schooling, and I found that I wasn’t interested in anything that was available to first-year law students.

I went to Brigham Young University. I was in Utah. I was not in Silicon Valley exposed to all this stuff. But all of my peers were going to go work for judges or volunteer at one institute or another, and I just could not find anything that was interesting to me. But I had a friend who had come out to Silicon Valley several years earlier and ended up raising some money, and they actually raised a decent Series A. This was back in 2011. They were a super lean team and suddenly the biggest blocker for them was hiring. They needed to hire engineers. So long story short, I spent my entire summer here working in Palo Alto, helping them recruit engineers and we recruited over a dozen engineers in four months, which was pretty phenomenal.

A lot of them were entry level and they weren’t full stack or these company engineers that we typically think of as being the unicorns that are hard to recruit, but nevertheless we worked hard to find all these people.

Cooley was the outside counsel for that friend of mine, and did their A round, and the partner came around one day, just doing regular business development, checking up on the company, seeing if they could be helpful. And I got to talking to them and they were like, “What are you doing here, doing recruiting? You’re a law student.”

And that exposed me to the world of venture capital and to transactional law. I went back and spent the next two years studying up on that, pursuing those as electives. Cooley ended up hiring me for my next summer and gave me a full-time position afterwards. I did my early career at Cooley and then came to Atrium. So that’s how I got into it.

When you start in a lot of these big law firms, especially the Silicon Valley-based law firms, most people are pretty evenly split between start-up work, M&A work and IPOs and public company disclosures. I found out very quickly that I was really only interested in the start-ups, so I doubled down on that early in my career, and extricated myself from a lot of the public company stuff.

And I’ve now realized the main thing startups want from an attorney is someone that is solely focused on their space. Knowing what the norms are and having the latest insights into the market are key because this industry changes and evolves so often.

It’s certainly the case where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. If you screw things up, then yeah, you’re going to incur some pain, but most of that stuff isn’t even very complex. When your an early stage venture-backed startup, there’s very much a standard way of doing things, reputational bits, understanding the rules of the game, the unspoken rules of the game, and a little bit of being an insider.

And one of the benefits that I can provide to clients, especially first timers or people who are Silicon Valley outsiders that are coming in, is to orient them to, ‘Hey these are the rules of the game. This is how things work, this is what people expect to see.’

Eldon: What are you telling early-stage companies about pitfalls to avoid these days?

Verzello: My goal, and Atrium’s goal, is to provide both legal and business advice so that our founders can worry about finding product-market fit or keeping money in the bank versus worrying about legal. My objective is for our clients to be protected but to spend little or no time thinking about legal.

I always advise my clients that they should not be interested in being innovative in their legal structure. In order for startups to move quickly, the legal should be simple to administer, simple to understand, simple for investors to get on board with, so they can focus all of their brain power on the products and their competitive advantage of the business.” And I think whether you’re an accountant or an attorney or whatever, entrepreneurs very quickly realize who is giving them quality practical advice.

Having represented over 20% of Y Combinator (YC) companies for the last few batches, I come across many of the same founder mistakes. One of the more common is that a founder will choose to incorporate as an LLC, I think they do this because they can write off a bit of the losses on their personal tax return.

But by the time they’ve decided to work with YC, they usually have raised some money – often in the form of a convertible note – and they end up having to flip their incorporation to a Delaware corporate (YC only invests in Delaware C-corps). What founders don’t realize is there are partnership tax issues for converting with debt outstanding in the business. We end up having to do conversions with $25,000 or $30,000 in legal fees and bring in tax and accounting specialists because the founders got some misguided advice at the beginning.

What I advise is that founders should not cut small short-term corners like incorporating as an LLC vs Delaware C-corp if they know they want to be venture-backed.

Eldon: What’s an example of a time you helped a company steer through a very complex situation successfully?

Verzello: I think that there’s a couple of different flavors of this. Ideally I’m having companies who are coming to me on day one to avoid having all these complexities. So that’s the gold standard. However, that’s not the reality for a lot of folks and so there’s lots of complex issues.

Recently I have worked with a lot of Canadian companies that have attracted US venture capital and now they need to flip into Delaware. There’s a lot of very interesting tax incentives that the Canadian government has put into place for R&D companies, and almost all our venture-backed companies are those. So helping them navigate how to put a Delaware holding company on top of an international operations subsidiary and get access to US capital markets while maintaining local tax laws privileges and labor markets. Those are complex issues that you can’t really Google and find the answer to in a high degree of confidence way. You have to know a lot about a lot of different areas of law.

The LLC issue comes up all the time. I’m currently helping somebody with a case where they’ve got dozens of folks on the cap table. It’s an LLC. They’ve been operating for years. They have revenue and traction to the point where they’re very interesting to institutional investors and people are saying, “We’d like to move forward,” but, “You’ve gotta be a Delaware corp for us to do that.”

There are good reasons why investors insist on Delaware corps, which I won’t get into now, but now we’re having to go through and realize… A lot of these things were done by somebody who had an adviser who was an attorney, who knew a little bit about corporate law and they were doing board consents, and signing paperwork and those were good things, but these people didn’t know anything about tax law or how partnership taxes work. And so now we have people with bunch of negative capital accounts, profits interest, and we have to unwind all of the tax issues.

And I’ll just say another thing, Y Combinator recently published their new post-money SAFE and I think there’s a lot of questions with that. It’s very similar to the old SAFE, in the sense of, if you ran a red line and looked at the edits, they don’t seem like there’s too many edits. But it really changed the nature of that transaction, the nature of the economics and the calculations behind that.

So I’ve had many conversations, both with investors and investor counsel and companies about this. There’s a little bit of this market assumption that the post-money SAFE is the new SAFE that everybody should be using” and I really feel like that’s an oversimplification.

I feel like now we have new tools in our toolbox. We have a pre-money SAFE, which is the original SAFE, and a post-money SAFE, and there are interesting situations where one is a better vehicle and a fairer economic instrument than the other. And it’s really, in my opinion, incorrect to assume everybody should always be using a post-money SAFE because that’s the latest and greatest. That’s just not true in my opinion.

Eldon: What kind of advice are you providing clients overall? What are you warning them about, telling them to avoid?

Verzello: I tell my early stage clients is there’s really only two areas that you’ve gotta be super focused on. Everything else is hard to screw up in a way that is really not fixable. So the two areas are company ownership, and this is basically your cap table, and IP ownership. If you get those two things right and you screw up a bunch of other stuff, you probably will be fine. If you do things wrong in those two areas, equity ownership and IP ownership, then that’s when you can find yourself in a really tough position.

And I’ve been in series A financing where we’re going through the standard minutia of ‘give me a list of everybody who has ever worked at the company, show me that they’ve all signed IP assignment agreements’ — I mean this is standard Silicon Valley stuff. All of us who have worked at tech companies have had to sign these as employees. You go through the list and you realize, ‘Oh wow we’ve got this one consultant who worked for us a year ago. He never signed his IP assignment agreement.’ I’ve been in a situation where at the Series A, the investors say, ‘Okay that guy was actually a key engineer. He did some interesting stuff on the product. We’re going to move forward, but we’re going to need to get his signature before we move forward with this because we feel like that’s a material risk.’ And I’ve seen clients where they get that signature and nine times out of ten, maybe more than that, the person just signs on the dotted line, they understand the agreement, they’re not trying to extract any value.

But I have seen people who say, ‘What’s in it for me? Why should I sign this now? You guys have been fundraising. Why don’t you give me something?’ In this case, they’ve found out and they probably have friends at the company and they were chatting and people knew that they were fundraising. You’d be surprised how many CEO’s calendars are just open for the whole company to see and you can just go onto Gmail and be like, ‘Oh wow the CEO has got a meeting with Andreessen this afternoon.’ Stuff gets out. So, in this case I’ve seen people who literally got 4x their stock in order to sign their IP agreement because they just put the company over a barrel and had all the negotiating leverage.

The other really terrible war story I have — and these are outliers. I’ve been investor counsel for a multi-hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars deal, and we found out that somebody was claiming to be an adviser, and claiming to have 5 percent of the company over little more than a bar conversation. And that company had been in litigation with this alleged adviser for four years, and couldn’t get the case thrown out, and had to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on litigation fees. And then we had to do all of this crazy stuff in the financing to account for that risk. And so I say, ‘Hey, get people to sign IP assignment agreements. If you’re gonna give an option grant or give ’em equity, make sure to have them sign the thing. Just follow the standard playbook but make sure you get it done and keep good records.’

Eldon: Because Silicon Valley has also been built on people having conversations at bars — I mean that’s sort of like the founding myth of the semiconductor companies… engineers who go and hang out and talk shop. These days, what do you tell people?

Verzello: There are some other facts with that particular case that wasn’t literally limited to a conversation, but that’s how it started and there was some stuff that happened from there.

Eldon: Gotcha like a handshake agreement that was never formalized, that kind of thing?

Verzello: Yeah or emails. Emails can be written agreements. It doesn’t have to be signed on the dotted line. If you agree to something, somebody might hold you to it. So be measured. Don’t just start throwing equity in your company around as like fun bar room conversation. Be measured in what you promise people. But, you can’t not have those conversations. You have to have those conversations. You have to bounce your ideas off people. You have to use the feedback, natural feedback loop of your peers and resources and you can’t have everybody sign an NDA.

I think the problem people get into is not by having conversations. People actually promise things and they think they’re just talking out the side of the mouth, but that’s not how things are understood, especially when it’s three years later and your company just got a $300 million valuation. Now people remember that conversation very differently, right? So just be measured in what you’re promising and be clear with people that you’re just having a brainstorming session and that’s it. There’s no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow without some more formal action.

Eldon: How should people think about working with you guys and what should they expect?

Verzello: The vision with Atrium is that we not only continue to provide world-class legal services but also build a platform where all legal work starts and ends in Atrium – providing transparency and collaboration between our clients and their legal team.

When engaging with Atrium, our clients are first and foremost engaging with a law firm but to know if it’s the the right fit, I usually try to gauge what type of firm and relationship they want. For example: do you want a firm that’s doing business the same way they’ve always done business, for decades, or do you want a firm that thinks innovatively, like you, and has a key objective to improve their services and operational efficiency over time.

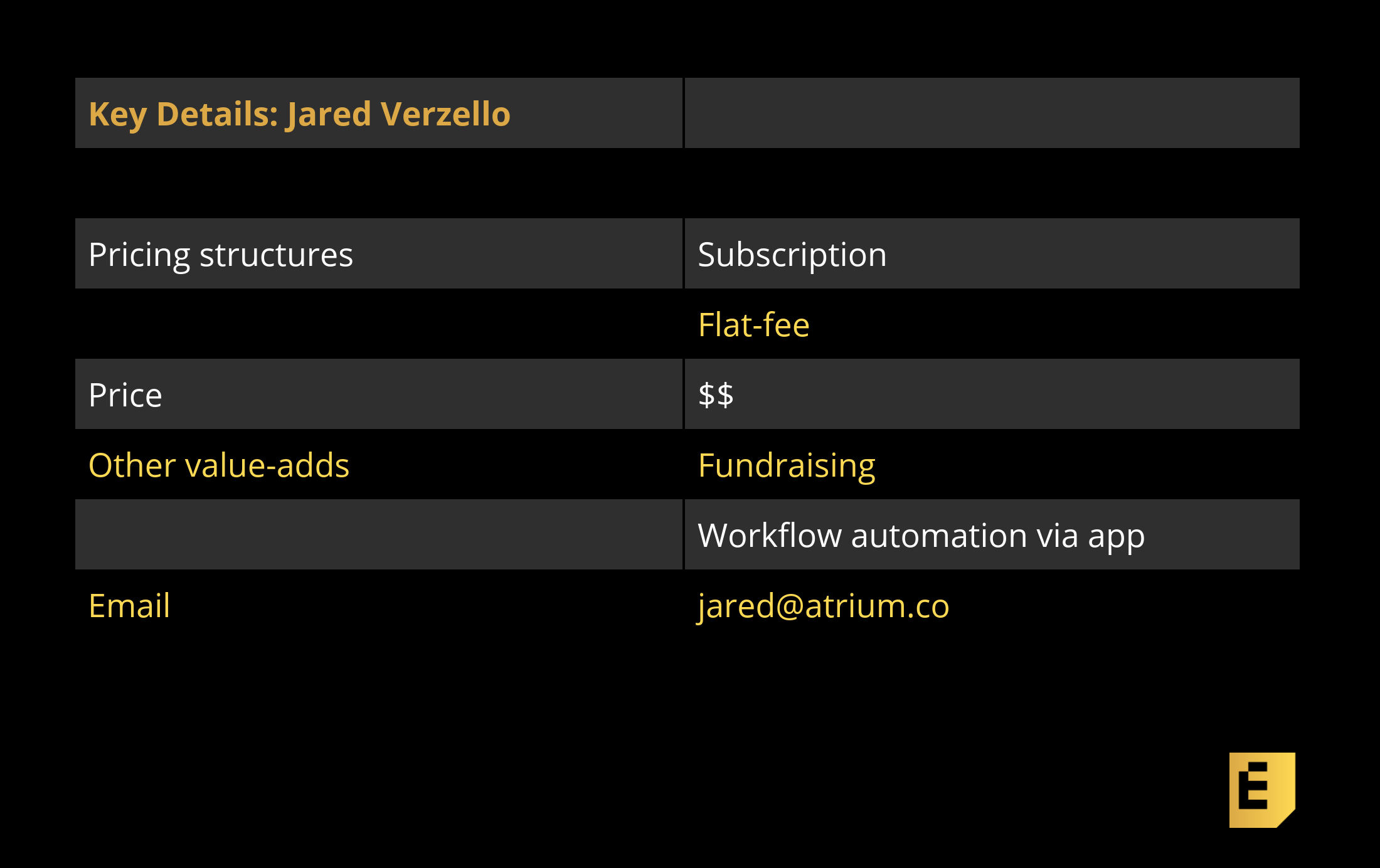

What’s also unique about Atrium is that our clients, of course, have a dedicated attorney but interactions are not billed by the minute. We pride ourselves in providing real business value and advice without the feel of a taxi meter running.

I think two things are a little bit of misnomers. One is people think that Atrium is going to be an order of magnitude cheaper than our competitors. I came from Cooley for example, where my rate was $700 an hour, and so people for some reason think that because Atrium has software it should be an order of magnitude cheaper.

That may be the case some day; that’s not the reality today. The main thing that’s different when you come to Atrium is dedicated time with an attorney. So we don’t bill by the hour. We offer transparent, upfront pricing. But they’re attorney prices. These are legal fees. You’re talking five, 10, 20 years of experience depending on what problems you’re solving and people are expensive, as we all know. So it’s probably cheaper, but it’s not substantially cheaper.

The second thing that people should understand, and it’s along the same vein, is you’re not buying a library of templates or a form library of legal documents. That’s what you buy when you go to Clerky and when you go to Shoobx and there’s a number of companies that do that.

Cooley Go put all those forms online for free. It’s like your taxes, right. If you are a W-2 employee you use Turbotax to file your taxes. That’s great because its simple. All of my friends who are entrepreneurs have a CPA because their taxes are much more complicated because they’re not W-2 employees. It’s not teed up for them. So when you go to a tax adviser, you don’t expect to pay anything for the form, you can get that online for free, you expect to pay for the advice and experience of the CPA.

But for some reason, a lot of my early-stage clients have this idea of “Oh well I’m just getting a form document, so it should be free.” And the reality is actually that’s not what you’re buying. If you just wanted to do a form, then you can go to Clerky or Cooley Go and those are great tools, but the catch is, you need to know how to use them and you need to understand the implications of what you’re doing. So if you do that, if you do those things because you’re experienced, or you’ve put in the time and are willing to invest your time into researching those things, you can probably have a really great experience on Clerky and Cooley Go and those services. If you need to leverage the experience and advice of a person and an expert, then that’s why you engage a lawyer. Just understand, reading a few blog posts does not make you an expert. I’ve been doing this for years and I’m still learning and getting better every day. The thing is, you can’t expect to level up on the type of knowledge that people pay hundreds of dollars an hour for quickly. It is just too complex. So, if you do things yourself you just need to understand that you are driving blind to some degree. Maybe that is the best you can do but you need to be honest with yourself about the cost-benefit analysis.

That’s why the same form agreement done on Clerky will cost you five times the amount through Atrium, because there’s an analysis that goes into it. We ensure that it’s the right form, we ensure that it’s filled out correctly and that our clients are making an informed decision about what they are doing. And there’s an entire issue identification process so that you as an entrepreneur can level up on these things or choose to focus your time elsewhere and then just completely outsource that entire workflow to a trusted adviser, an Atrium attorney.

So it’s not a right or a wrong thing; it’s a fit thing and it’s understanding why. I had a conversation with someone literally yesterday. They had raised $45,000. Half of that was from a traditional early-stage investor who does pre-seed checks to keep their finger on the pulse of a company. They referred them to me. I talked to them and I actually told them that, ‘I think you should go with Clerky until you guys raise some money. Then we should revisit this conversation if I can be helpful.’ I gave them a roadmap to the landmines to avoid, of the things that typically go wrong. You know, filing those 83(b) elections, watching the cap table, watching the promises, making sure everyone signs their IP agreements, making sure the board consents to certain corporate actions. And you know, with some luck, I’ll probably see them in six months. And that’s the best thing for them.

Founder Recommendations

“Jared is an all-star. Explains everything very clearly and understands that I don’t have a working knowledge of the law. Takes his time to hop on a quick call to explain what clauses in certain documents mean and is good for strategy purposes as well. I’ve seen Jared working on weekends to turn things around for us. He’s patient, clear and willing to go the extra mile to help us understand. THANK YOU JARED!” — AJ Shewki, Prague, Czech Republic, cofounder and CEO, LIV

“Jared gives clear answers, not a bunch of legal CYA. He is easy to reach and usually quick to respond.” — Chris Lau, San Francisco, cofounder and CEO of Precious

“Jared was amazing. He was proactive, a great communicator and helped us navigate through our incorporation process seamlessly.” – Amanda Chan, Waterloo, Canada, cofounder of BigBridge Technologies Inc.

“I liked working with Jared, I think he really took the time to explain how everything works. He was clear, quick to respond, etc.” – A cofounder of an early-stage startup

“Jared has been a great advocate for Kinside. He’s highly responsive and added tremendous value in supporting our seed round of fundraising. Having worked with GCs before, I’d like to add that Atrium has been an awesome partner, helping me make our legal fees predictable and navigate the complexities of starting a new biz.” — Rob Bircher, San Francisco, cofounder and COO, Kinside, Inc.

“As a very early-stage company, one can be exposed to so many vulnerabilities and even potential bullies when it comes to legality. Jared (my attorney) has been knowledgable, understanding, and adaptable and the value of that to a startup cannot be overstated.” — Leslie Fong, San Francisco, founder and CEO, VENIM

“Our legal counsel, Jared Verzello was available both day and night – allowing us to close our seed round within weeks.” — Stephen Klein, Los Angeles, CA, cofounder and CEO, Ono Food Co.

“Our attorney strikes me as intelligent, professional, and reasonable. I enjoy that we often don’t feel rushed in our conversations… I also feel confident that our attorney will be helpful, especially re: corporate matters.” — Tim Hahn, Producer, Kuku Studios