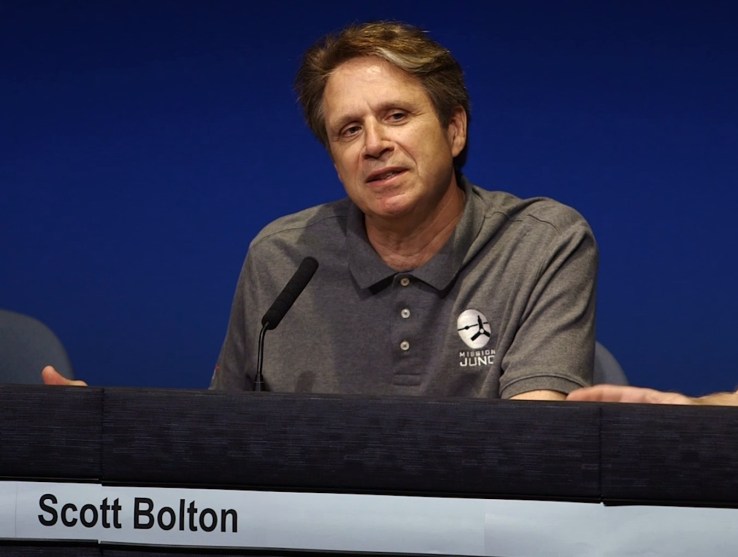

The Juno probe has just made its long-awaited rendezvous with Jupiter, kicking off 20 months of unprecedented planetary science. We cornered the mission’s principal investigator, Southwest Research Institute’s Scott Bolton, during a briefing at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory — and he was more than happy to talk about all the cool new gadgets packed into the craft.

“We set out right from the beginning to try to create the most efficient design we could,” said Bolton (“the engineering team liked clean lines,” he added). “In the case of Juno, because we were going into such an extreme environment, a lot of those designs needed to be retested and rethought.”

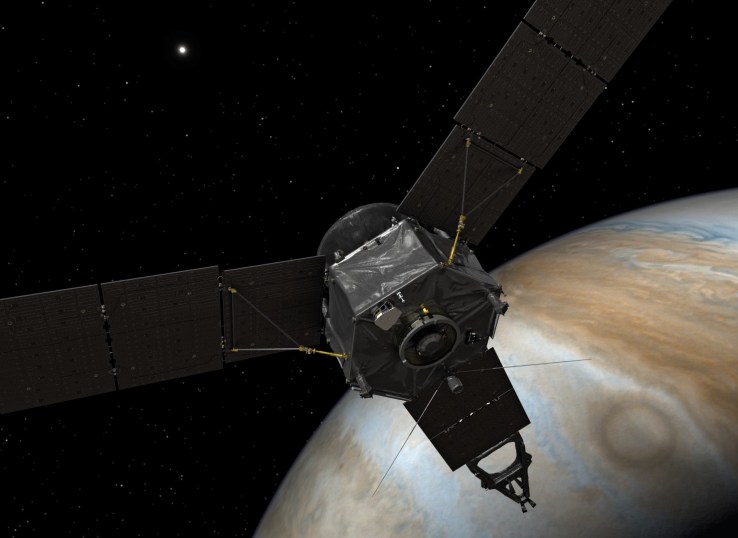

Jupiter is, of course, huge, and so are the forces that surround it. Juno will encounter extremely high levels of radiation and powerful magnetic fields, which meant all of the instruments needed to be very securely shielded. But fitting them all into the limited space of the “electronics vault” was no easy task.

“It took enormous amounts of work. I can’t tell you how long it took,” he said. “We had teams of engineers and scientists all trying to solve this jigsaw puzzle: how do we get these boxes into this, how do we twist them, how can we turn this? And then when we got the boxes in, we realized we had to put the cables in.”

It’s all solar-powered, and in January, Juno passed Rosetta’s record, becoming the most distant solar spacecraft in history.

“We took the very best that was available on the entire planet.” said Bolton. “These solar panels are really efficient, and they’re very large.” 261 square feet, to be exact — not a lot for a terrestrial solar farm, but almost too big for a craft that has to be launched into space.

Since Juno is Bolton’s baby, he’s looking forward to the data from every device on there — but he’ll be keeping an eye on one especially.

“I’m particularly tuned into what we call the microwave receivers, or microwave radiometers. These are the things that are going to look below the cloud-tops for the first time on Jupiter,” he said. “It’s a brand-new kind of instrument. We’ve never flown anything like it.”

The microwave radiometer takes up a lot of the vault’s surface area, consisting of six huge antennas tuned to specific frequencies. Each will penetrate to a different layer of the gas giant, and as Juno spins during each orbit, the six together will provide a cohesive look at what’s under the famous swirling surface of Jupiter.

“We don’t really know what to expect,” said Bolton. “I know there’s going to be a lot of discoveries with that, so I’m excited. It’ll produce something for the public that they’ve never seen, which is a three-dimensional image of what Jupiter’s atmosphere really looks like.”

We’ll be keeping up with Juno’s progress during its 20-month mission. The first images from the visible-light camera, which will get a never-before-seen view of Jupiter’s north pole shortly after orbital insertion, should show up within a few days of arrival.