If you’ve got more than a handful of 3D printers or other devices running at a time, it’s a full-time job keeping them going — removing and packaging products, tweaking settings, pushing “OK” after minor errors, that sort of thing. Why not have a robot do it for you? Tend.ai is a new company that helps you train collaborative robots to perform machine tending, something generally reserved for bots serving heavy industry.

“This whole thing started because a friend of mine down the street literally has 20 3D printers, and his wife was having to run out every three minutes to keep them running,” said Mark Silliman, co-founder and CEO of Tend.ai, in an interview.

Silliman’s company Smartwaiver was acquired in December, and his co-founders have also had a few recent exits. Security head James Gentes sold his analytics company The Social Business last year, as well, and backend engineer Robert Kieffer was part of Zenbe, which Facebook bought in 2010.

So the whole thing began in February as something of a lark, perhaps to fill the rainy winter days of Bend, Oregon, where the company is based. Instead of employing a beleaguered spouse, why not use one of those fancy new collaborative robots meant for operating with and around people? Turns out they’re not especially easy to configure, since right now the industry is more focused on factories and assembly lines, not DIY operations.

Working with an “integrator” to customize the platform, and getting the special hardware for computer vision or web monitoring can cost tens of thousands on top of the robot itself.

“We basically spun up this system that moves all this data to the cloud,” said Silliman. “Now you can use a $100 webcam to do OCR and the whole nine yards, AI and machine learning, without having any of these resources in-house. And you can do it without modifying the machines or voiding their warranties. You can use any robot, any webcam, and it’s just plug and chug.”

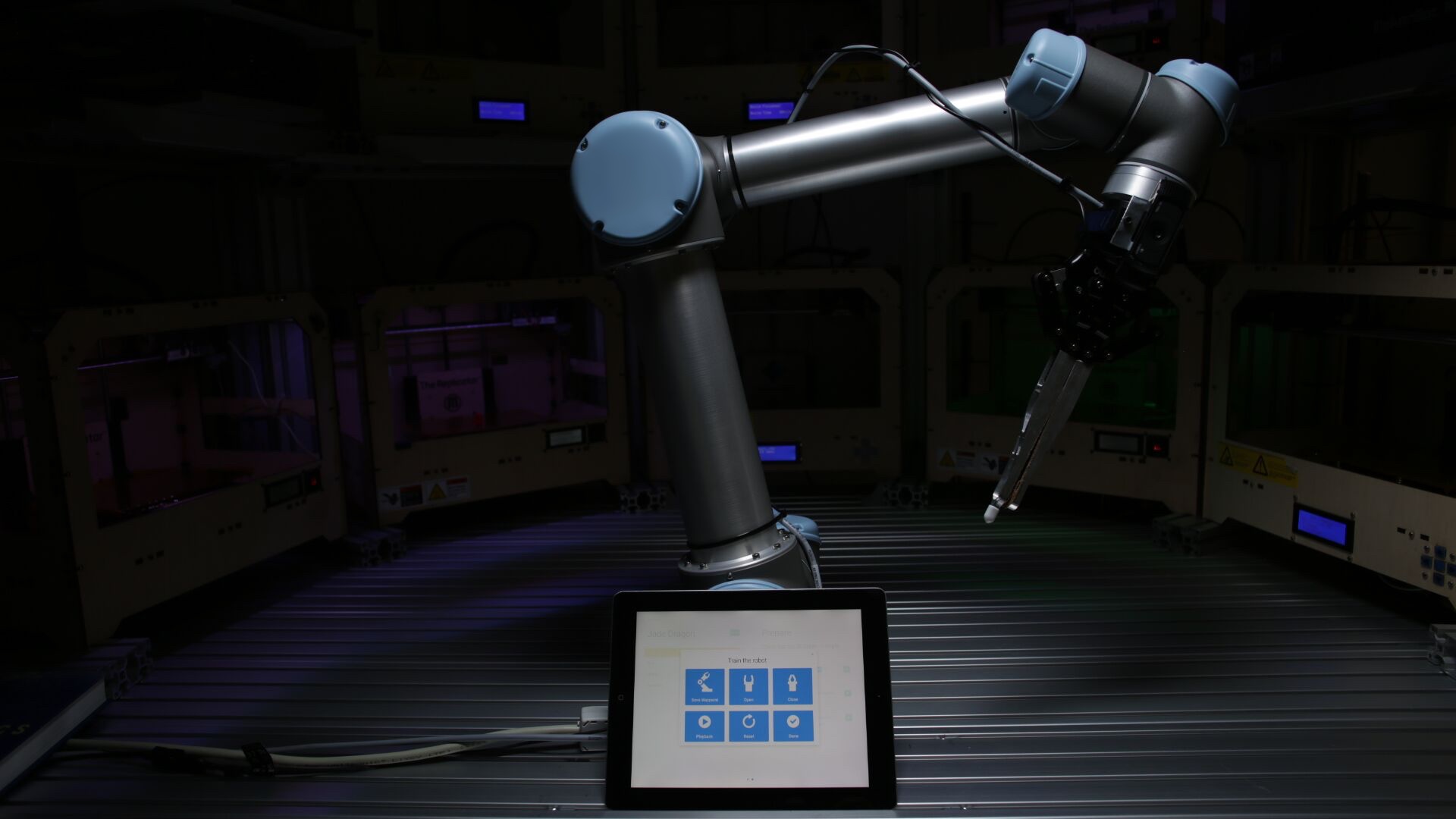

The Tend.ai system consists of a small computer, provided for free, that acts as a thin client, passing data to and from the robot and webcam, which you attach to its arm. All the configuration data and instructions are stored in the cloud.

Training the robot is an entirely physical process. “Users never write code,” Silliman said. “They literally take the robot and pull it around by hand — these are collaborative robots, you can touch them — and train it, this is where the buttons are, this is where the screen is.”

For instance, a laser-cutting machine may indicate that it’s done on its touchscreen; you can teach the robot which part of the screen to read, then follow-up actions like dismissing the “job done” notification, opening the lid, removing and placing the product, then closing the lid and selecting a new job. The physical actions (XYZ translations, grip widths, etc.) would be learned by the robot’s own operating system, but managed and deployed by the Tend.ai box. It could also, say, react differently if there was an error or cancel the next job if there’s not enough material.

Of course, if you are using a well-known machine like a common 3D printer, you won’t need to train it at all — Tend.ai’s database will already have that data. If not, your training data will be generalized and used to help others set up their own shops, who in turn add to the knowledge base for that model.

The business model is a standard SaaS one, with a subscription model that Silliman said they’re still working out the details of. But if it works as advertised, Tend.ai’s system could allow machines to run 24/7 without human intervention — lowering costs, increasing productivity or both. Of course, there are a couple of objections worth addressing.

“People say all the machines should be networked,” said Silliman. Printers and robots naturally aware of each other would not require an abstracted organizational layer like Tend.ai. “I would absolutely love that. But the truth is, people stay with machines for 20, 30 years. Because they work great! So waiting for the IoT dream isn’t always possible.”

Besides, a humanoid robot using a system like Tend.ai’s is fundamentally flexible.

“You could design a machine to do something really well, and faster than a robot with a webcam. But the point of the robot is that it’s agnostic, it can quickly adapt,” Silliman pointed out. “You can retrain the thing in 30 minutes.”

There’s also opportunity for a big data or machine learning play. If you’re operating hundreds or thousands of these devices, you’re building quite a database of things like uptime, part wear, material usage and preference, and also video of operation that can be used to improve industrial computer vision systems. That’s all pie in the sky right now, of course, but an interesting prospect nonetheless.

The company is only a few months old, and just now appearing in public. A beta with “10 to 20 customers” will go live in July, on the strength of which Tend.ai hopes to raise perhaps $2 million to fund further hires and development. Full operations should be a go toward the end of the year or early 2017.