In the spring of 2015, a group of Chinese scientists modified the DNA of 54 embryos using CRISPR/Cas 9 technology. Twenty-eight of those embryos were successful, but 26 — nearly half of them — failed, setting off a heated debate throughout the scientific community on the ethics of altering human genes.

Regulators don’t currently allow the use of CRISPR on human DNA in the United States, but researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have proposed the first human study using the technology. The proposal would allow these researchers to make T cells with the ability to attack three inherited types of cancer.

A federal biosafety and ethics panel gave Penn the go-ahead earlier today to conduct research on human patients, but the idea will still need approval at the proposed medical centers where the research will potentially be conducted, and will need the OK from the Food and Drug Administration.

The proposed early trial will involve up to 15 patients and help researchers determine the safety and viability of the technology on humans. It will also get solid backing from the Parker Institute of Cancer Immunotherapy, tech billionaire Sean Parker‘s organization, which formally launched this spring to collaborate with research institutions to obliterate cancer.

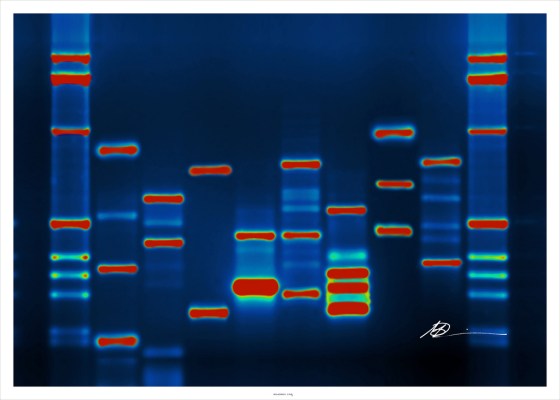

Scientists are still hotly divided on the ethics of manipulating human DNA. The technology works by snipping out strings of genes to do all sorts of crazy things like getting micro bugs to make spider silk or eliminating DNA that causes fatal diseases.

On the one hand of the argument, use of CRISPR could mean babies born today never have to inherit a debilitating illness from their parents and the possibility that we could one day simply cut out any traces of genetically inherited cancers.

The flip side of that means messing with our genetic makeup without currently knowing the whole outcome. The Chinese experiment produced a bunch of other unintended effects on some parts of the genome, causing almost half the embryos to die.

Penn’s lead on the proposed study, Dr. Carl June, acknowledged in a webcast earlier today the technique to cut out the undesirable genes is not perfect — some PD-1 and TCR genes, the lack of which have been shown to help reduce lung tumors, remain. However, what’s left is at a low enough level, according to the data, that it helps particular T cells called CAR T cells better attack cancer cells.

But the proposal from Penn is a leap ahead of what many thought would be happening in the field. Gene-editing company Editas (which went public earlier this year) said it would hold the first human clinical trials using CRISPR in 2017.