Understanding the complex order behind the apparent chaos of a tropical storm or hurricane is no easy task, but it’s worthwhile to try — such storms deal death and destruction globally, and the better we know them, the better we can prepare for them. A NASA blog post highlights some of the work and improvements in storm prediction and simulation being done at the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office.

Over the last decade, the systems used by the GMAO have advanced a great deal: like so many other researchers and industries, these climate scientists have benefited both from a greater volume of data and plentiful computing power with which to sift through it.

In order to predict the paths and intensities of future storms, GMAO scientists must create simulations — computer models of storms that, for lack of infinite processing power, must make compromises in terms of accuracy.

“In the model we basically transform Earth’s atmosphere into little ‘cubes’ and in each cube the fundamental equations controlling motion, energy and continuity of the atmosphere are solved,” said GMAO meteorologist Oreste Reale in NASA’s post. “The smaller the size of the cube, the more realistic the representation of the atmosphere.”

Those cubes have shrunk from about 31 miles across to 8 over the last decade — at great computing cost, since they also include far more data, but also to great benefit.

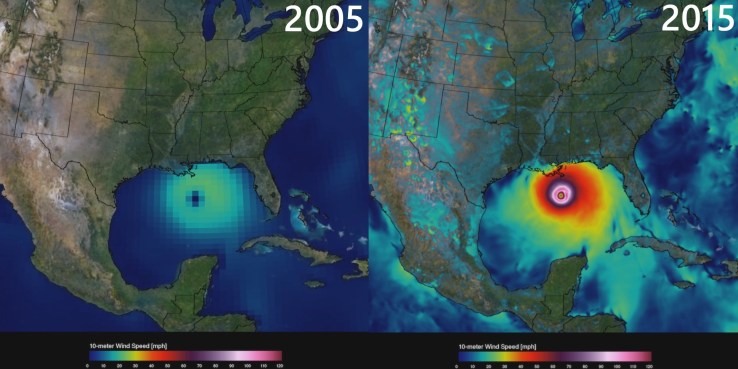

As an illustration of how far models have come, here are two models of Hurricane Katrina, one from 2005 and one from 2015:

The higher resolution isn’t just for looks, either. 2005 models drastically underestimated the atmospheric pressure levels the storm would reach; 2015 models come much closer.

More computing power also means improved methodology. Scientists now run a series of storm simulations, each with slightly tweaked settings, producing a variety of possible paths and intensities; these can be considered individually or averaged together. You can see this in action in the short video accompanying NASA’s post.

Reale is on a team in the GMAO that considers new data sets and computer models and makes sure that they are working together properly.

“We need to add complexity all the time,” Reale said, “and nobody here is afraid of doing that. You don’t want a simple solution. If it’s simple, chances are it’s not true.”