Australian physicists, perhaps searching for a way to shorten the work week, have created an AI that can run and even improve a complex physics experiment with little oversight. The research could eventually allow human scientists to focus on high-level problems and research design, leaving the nuts and bolts to a robotic lab assistant.

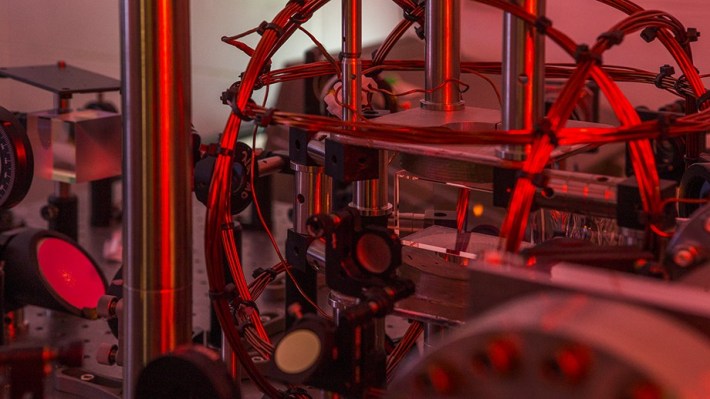

The experiment the AI performed was the creation of a Bose-Einstein condensate, a hyper-cold gas, the process for which won three physicists the Nobel Prize in 2001. It involves using directed radiation to slow a group of atoms nearly to a standstill, producing all manner of interesting effects.

The Australian National University team cooled a bit of gas down to 1 microkelvin — that’s a millionth of a degree above absolute zero — then handed over control to the AI. It then had to figure out how to apply its lasers and control other parameters to best cool the atoms down to a few hundred nanokelvin (i.e. a billionth of a second), and over dozens of repetitions, it found more and more efficient ways to do so.

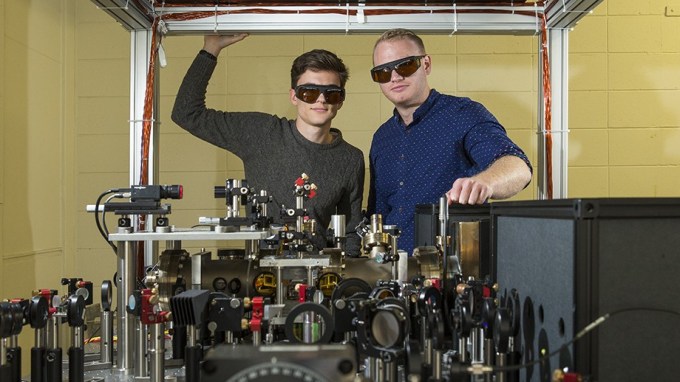

“It did things a person wouldn’t guess, such as changing one laser’s power up and down, and compensating with another,” said ANU’s Paul Wigley, co-lead researcher, in a news release. “I didn’t expect the machine could learn to do the experiment itself, from scratch, in under an hour. It may be able to come up with complicated ways humans haven’t thought of to get experiments colder and make measurements more precise.”

Bose-Einstein condensates have strange and wonderful properties, and their extreme sensitivity to fluctuations in energy make them useful for other experiments and measurements. But that same sensitivity makes the process of creating and maintaining them difficult. The AI monitors many parameters at once and can adjust the process quickly and in ways that humans might not understand, but which are nevertheless effective.

The result: condensates can be created faster, under more conditions, and in greater quantities. Not to mention the AI doesn’t eat, sleep, or take vacations.

“It’s cheaper than taking a physicist everywhere with you,” said the other co-lead researcher, Michael Hush, of the University of New South Wales. “You could make a working device to measure gravity that you could take in the back of a car, and the artificial intelligence would recalibrate and fix itself no matter what.”

This AI is extremely specific in its design, of course, and can’t be applied as-is to other problems; for more flexible automation, physicists will still have to rely on the general-purpose research units called “graduate students.”

The team’s research appeared today in the journal Scientific Reports.