Two and a half years ago Bitlock set out to crowdfund a smart bike lock at a time when hype around connected devices was surging and goodwill in crowdfunding platforms was buoyant.

Since then both categories have taken some confidence knocks and served up disappointments aplenty.So what happened to Bitlock? Did it ship, and if so, did its smart device live up to expectations? What problems did it run into? And what does it think of the crowdfunding process with the benefit of hindsight?

Crowdfunding hardware is an especially tough act to pull off. Some very high profile projects have crashed and burned. Others that went on to attract VC investment after a successful crowdfunder have still struggled with delays and rising competitive threats. Product problems seem to be a given. Being small and scrappy is not usually a recipe for mass market success in the fiercely fought consumer electronics space.

The bottom line is that hardware is hard. It’s a long-distance marathon of challenges, even if you secure enough up front funding to build your gizmo. Sometimes money itself can derail the dream — investing project creators with too much confident, encouraging bad decisions and poor budgeting, leading to wastage and worse.

Throw in a bunch of excited crowdfunding backers who bought into your initial enthusiasm and are inexorably bound to the fate of your project with their cash and high hopes, and, well, your inevitably long and bumpy development process is going to feel even more fraught.

I covered the original launch of Bitlock’s crowdfunding campaign back in October 2013, at a time when crowdfunded technology projects-in-the-making were considered exciting and experimental enough to be worth writing about. These days we’ll rarely cover crowdfunders pre-shipment — which just goes to show how much of the sheen has rubbed off the process. (Not to mention how much out-and-out nonsense gets pitched on these platforms.) Vapourware isn’t very interesting even if you’ve made a video that convinces a bunch of people your product will one day exist.

The original idea for Bitlock, as pitched on Kickstarter, was a smart bike lock that would let people lock and unlock their own bicycle using an app on their phone, doing away with the need to carry bike keys and enabling additional capabilities — such as the ability to create and manage virtual keys that could be shared with others to share access to a bike; ride tracking and analytics via the Bitlock app; and location mapping of your bike to make it easy to remember where you parked.

It was pitched as a consumer product that would encourage collaborative consumption, convincing people to share their bike with friends, co-workers, neighbours.

The Bitlock Kickstarter pitch went on to meet its funding goal and raise just under $130,000 in total from 1,268 backers. It had an original estimated delivery date of July 2014.

Under the ‘Risks & Challenges’ subhead of the original campaign page, Bitlock’s creators expressed confidence in being able to ship on time — writing:

According to Kickstarter statistics, more than 84% of the top successful Kickstarter projects shipped late. We don’t want to be one of them. We strongly believe in “under-promising and over-deliving”. Because of that we decided to add enough time margin to our estimated delivery date to make sure BitLock is shipped on schedule. We understand that we may lose some backers because of the mid-summer ship date but we believe we can later bring them onboard to join the BitLock family once we are in full production.

In the event, the team was not able to avoid the all-too-frequent fate of being yet another late shipping hardware crowdfunding project. Two and a half years on they have just recently fulfilled the last Kickstarter pre-orders. They shipped in two batches meaning some backers had a smaller delay than others but all backers had to wait longer than promised to get their hands on the lock. Around half the backers had to wait a year longer to get the device, says founder Mehrdad Majzoobi. For the other half it was closer to one year, nine months.

“We are bootstrapped at this point. One of the very few hardware startups that I know have bootstrapped. It’s really hard because expenses for tooling are really high. We didn’t really raise much compared to a lot of Kickstarter campaigns. And so part of the delay between the first and second batch was we needed to find a way to finance the second batch and it took us a couple of months to figure that out,” he explains.

“Also we wanted to get as much feedback as possible for the first production run so that we could fix those issues in the second production run. And also in applying those fixes we had to make some changes to our tooling and stuff like that to address those issues and all of that took us around nine months.”

Despite some lengthy delays Bitlock did deliver the goods to its backers. So this is by no means a story of sensational crowdfunding failure. But even so it’s fair to say that the startup has not been able to prove out its original consumer smart lock proposition, either. Indeed, it is now largely focused on a b2b play, rather than on selling smart locks to individual consumers (although it is still selling via its website and other retail outlets such as Amazon.com).

Bitlock’s b2b proposition packages its smart lock hardware as an automated rental system, in conjunction with fleet management software and a rental app that takes payment via Stripe which the team developed since the original crowdfunding campaign. The idea is, instead of small businesses/companies/organizations needing to shell out a lot of capital for expensive bike docks to run rental schemes — or have a bricks and mortar location where bikes can be stored and rented — Bitlock’s connected lock plus app combination allows for rental operations to be set up at lower cost and with leaner infrastructure requirements.

Rental bikes can, for example, be sited right outside a hotel, locked to street furniture, to capitalize on passing demand from tourists. Payment is handled in-app, and various incentives and penalties can be provisioned through the Bitlock system to, for example, encourage users to bring the bikes back to the same location where they were rented from. The whole operation probably only needs a couple of people to check bikes and handle any questions/problems from people renting the bikes, reckons Majzoobi.

“[Our original p2p bike share idea] didn’t get people very excited because a lot of people didn’t want to share their own bicycles. But it was just a hypothesis that I realized, the first couple of days, that idea is not going to fly,” he says. “Right now we target system operators — somebody who wants to dedicate some capital to purchase 200 bikes or 100 bikes in order to start a small network in the city. Or a school, a campus, or a company campus or a real estate property.”

It’s still early days for Bitlock’s b2b business pivot, so this application of its smart lock tech hasn’t been proven out either. But Majzoobi is markedly more enthusiastic about the potential here vs the consumer space.

At this point the team has three “relatively larger systems”, as he puts it, up and running with rental operators, along with several small pilots. “We have a relatively large system [its largest rollout to date] in Oslo, Norway that went live a couple of days ago with 50 bicycles. The next biggest one is 30 bicycles in one network. We have about six systems, most of them are in pilot phases. That means they are testing with 15 bicycles or so to really understand how the system works and then expanding to 50 bicycles or so.”

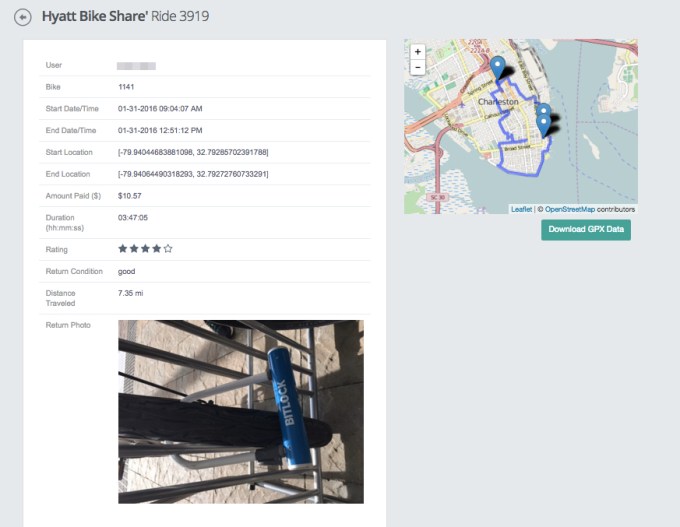

Another small pilot of the rental system is in Charleston, sited in front of a Hyatt Hotel. That will be expanded to 250 bikes this summer, he says — with the intention being to put bikes in front of every hotel in downtown Charleston.

The b2b smart bike lock business model is clear, reckons Majzoobi — talking up the “huge advantage” vs extant bike share systems because Bitlock’s leaner offering is “an order of magnitude less expensive” than, for example, those that require stationary docks for bikes to be placed into.

“We are able to generate around $50 per bike per month just by providing the technology to the operators — and that recurring revenue will be somewhere close to $400 or $500 per year per device which is substantial revenue compared to the cost of the lock,” he says. “Also it’s a substantial value proposition to the operator because lots of their next best alternatives in many cases is to go with a station-based system which costs around $6,000 per dock (including the bike). We can get that under $500 — the bike and the lock. So it’s almost a 10x reduction in set up costs.”

Returning to Bitlock’s consumer story, where the startup’s vision originated, it’s clear that not every backer has been happy with the smart lock they received. TechCrunch has been contacted by some backers who complained about problems with batteries leading to their bike to be rendered apparently unlockable — short of taking out a hacksaw.

Other backers have complaints about the responsiveness of the Bitlock software. Or about delivery issues. One told me he gave up on using the lock because, although it did work as promised, it was not as physically small as he would like. “The amount of stuff that has to fit into the lock bolt to be smart means there are no small smart locks yet. I prefer smaller locks,” said this buyer. So it’s evident there are a range of complaints associated with the device.

But again, it’s not all bad; there are also happy customers who praised the product as working as they’d hoped. One even lauded its ability to endure harsh Canadian weather conditions.

Majzoobi confirms Bitlock ran into a series of manufacturing issues during the complex process of turning a prototype into a robust consumer product. The first Bitlock production batch was especially problematic (early adopters take note!).

The device is clearly pretty challenging to build given where and how it’s used. He describes the lock as “very challenging on many levels” — because it’s used outdoors and “doesn’t get treated very well”. “It gets dropped, and it sits out under the rain, under the sun. And it has a battery in it which has to last for a very long time. There’s so many design constraints.”

Waterproofing was one problem the team encountered, meaning they had to change their design to improve its ability to withstand water ingress and humidity. Another delay-causing problem was related to the battery. Firstly they ran into an assembly problem, after the battery compartment came loose on a batch of locks meaning the team had to perform a manual fix on all the affected locks — which took a chunk of extra time. But they also ran into problems with the battery itself. And specifically with battery lifespan.

“It’s hard to test a battery for its lifespan,” says Majzoobi. “Everything looks fine but over time [problems arise]. The supplier says the shelf life of the battery is 10 years but sometimes their batteries die before then and it’s really hard to know unless it’s a veteran supplier and other people have used them and you have full confidence.

“Especially as we use a special battery which is an AA form factor. It’s a lithium battery but it’s an AA form factor and a 3-volt battery. Most of the 3-volt lithium batteries come in a coin form factor or a different form factor… so it limited the number of suppliers we could work with. There are only one or two suppliers that meet this battery. So we had some unfortunate issues in the first production run that we resolved.”

Another issue that caused delays was a shipping/logistics problem — hence complaints from some backers about not receiving their locks. Initially Bitlock was handling shipping themselves, another time-consuming process, but now it hands that off to a shipping partner. But again, getting those relationships worked out and efficient links in supply and distribution chains forged takes time. And crowdfunded hardware startups are likely to be working against the clock.

The big delay between shipping the two production batches of Bitlock was caused by a cash flow issue. Essentially the Kickstarter money was enough to fund making and shipping the product to only about half of the backers. So the team had to find a way to finance the second production batch themselves. That meant working with their manufacturers to secure financing terms. They also had to get inventory financing to be able to afford to fund a second production run — in order to fulfill the final 500 Kickstarter orders. Minimum component order quantities meant they had to make a larger second batch than just 500 units, hence needing to look for financing.

“We have a financier that pays for the inventory and we sell from that inventory and we give them interest when we sell. So that helps a lot with the cashflow,” says Majzoobi, adding: “I’m very glad we shipped, it’s just sometimes such delays can really kill startups because every day that you don’t ship you have day to day expenses that you’re paying for for day to day operations. You go deeper down.”

And then there’s another, arguably more painful category of problem: your own users. People don’t always guess correctly how to use your device. Nor do they always handle it as you think they will so things you thought were simple turn out to be problematic. This education challenge appears especially acute when it comes to so-called ‘smart devices’ where expectations of ‘automagical wizardry’ abound — meaning frustration thresholds, should a device fail to work perfectly immediately, can be very low indeed.

User-related product issues certainly stretched the resources of Bitlock. Turns out, for example, that users whose locks die because the battery croaks prematurely can still unlock the device by externally powering it via an external micro USB port sited on the lock. The problem is this port is covered (for waterproofing reasons) so people don’t know it exists.

“There are so many things we’re right now working on our knowledge base to tell people how to replace the battery,” says Majzoobi. “We have to tell them explicitly. It’s not in our user manual. And we’re putting information in our knowledge base help desk. There are so many things we are still setting up, our knowledge base is not complete, we get a lot of questions.”

We are overwhelmed. We get about 200 emails a day and you’re trying to answer as many as we can.

“Honestly we are not really doing a good job at our communication,” he adds. “We are overwhelmed. We get about 200 emails a day and you’re trying to answer as many as we can. Lots of these questions are repetitive and once we set up our knowledge base we’re going to be able to direct them to the knowledge base to get the answer.

“We didn’t really have time as a small startup still struggling with all these operational aspects of customer service, logistics, shipping. We have set up our logistics and it’s now very fast but previously we were just shipping ourselves which was an insane amount of work. Now we have the logistics set up and now we just send the orders every day to a fulfilling partner and then they ship it. All these operational pieces for hardware startup is just overwhelming and I’m trying to catch up with most of these things and falling out with the customers.”

It’s certainly true that good communications are essential for a business to keep customers on side. But perhaps there’s a more significant issue to consider here — specific to the smart device category. Namely, how compelling are smart devices as a consumer proposition at this nascent point? It seems that consumer expectations of what these gizmos will deliver are simply far too high — meaning disappointment is embedded from the get-go, thanks to technology limitations and what are often rather incremental advantages over apparently ‘dumb’ (i.e. not-Internet-connected) alternatives in the first place.

For example, Bitlock’s pitch that you’ll be able to ditch your bike key never really struck me as massively compelling. A bike key can just hang on your keychain along with your other keys. It’s hardly a massive extra burden in your pocket.

Point is, the easiest to use/operate devices tend to be very simple tools. A physical key, for example, is a very simple device that allows a human to interface with a complex locking mechanism without needing to know how the latter works. Nor does it require a user manual explaining how to insert and turn it. Its operation is as basic as its body is robust.

Yet once you add connectivity to any device you are inevitably introducing more complexity. And this is the really big challenge that smart devices are grappling with. So if the primary thrust of your smart device marketing is that your connected gizmo will be more convenient than the dumb old alternative, well, you might want to rethink that pledge.

Smart devices can certainly be designed to include many interesting-sounding additional features vs non-connected devices. But whether they can also be designed to always be effortless easy to use is up for debate. And in Bitlock’s experience it’s clear that even something as apparently simple as a smart bike lock has caused its users plenty of frustration.

“The main issue with the product right now is the user experience,” says Majzoobi. “The user experience needs to be improved… At the end of the day I want a kind of product that doesn’t need any sort of education; I don’t need to educate the user how to use it very much; it’s something that they get easily. But right now there are some aspects of the product that need to be mentioned to the user — you’re not supposed to use it this way, or you ‘re not supposed to do this — that kind of education will take resources which will indirectly add to your cost of business.”

One example of a physical foible that has frustrated Bitlock users is if the lock is locked with the U-bar pulling away from the locking mechanism (as is often the case when people secure their bike to a piece of street furniture) it puts the mechanism under tension and means that when the user presses the button to unlock it the lock will not unlock.

“The workaround is they have to apply slight pressure, inward pressure, to cancel that tension on the locking mechanism. Once they get it they know they have to do this but the user experience in that moment is not very pleasant – oh look my bike is stuck!

“It’s the same thing when you use a key. If the U-part is getting pulled you have to wiggle with it, or you have to insert a little bit of pressure… but since you don’t have the haptic feedback you don’t know what the locking mechanism is doing inside the lock and then you feel like the lock is stuck and I can’t do anything about it.”

While there’s evidently a very simple fix for this issue, the wider problem is that users don’t find the fix on their own because they were expecting the smart lock to be smarter — i.e. to have been engineered without any such usage wrinkles. And so they end up disappointed. Or angry. Or both.

Are user expectations for smart devices too high at this nascent stage, I ask? “Absolutely,” says Majzoobi. “It’s because people who are adopting this kind of product they are looking for a kind of experience they’re not getting with their non-smart, non-connected product.”

Another recurring usage problem Bitlock has had to deal with is people complaining the lock won’t connect to their phone. The fix for this is also simple; you have to have the app always running (either in the background or foreground) for it to be able to communicate with the lock. But again this facet of the UX has proved a problem with users.

The user mentality is that if I’m going to reach into my pocket, open the app, and then connect to the lock it’s the same amount of work as if I reach into my pocket get the key and unlock it.

“Lots of the users email us and say the lock won’t connect to my phone and we realize that they’re not even running the app,” he says. “That’s something that’s very obvious to us but the user expectation is that the lock should be always connecting to my phone because it’s close to my phone. The user mentality is that if I’m going to reach into my pocket, open the app, and then connect to the lock it’s the same amount of work as if I reach into my pocket get the key and unlock it and it’s a completely valid argument but at the same time there are some certain limitations in the technology.

“We can actually do that on Android because on Android you can run a background service and it’s running all the time but iOS does not allow that. You cannot have background process that uses your bluetooth. So we were looking into iBeacon and some other ways to see if we can provide that experience.”

Of course this user expectation problem is compounded by smart devices generally having a higher price tag than non-smart alternatives. So if prices come down, users might be more tolerant of needing to wiggle their smart whatnot to get it to work as billed.

“Most of the smart locks are three or four times more expensive than a regular lock in any category,” notes Majzoobi. “In our case we’re $129, a regular lock is $40 or $50. If you can close that gap you can also manage the expectation. If the user is paying $50 for a non-smart lock and $50 for a smart lock and the experience is not different then they will go for either of them, it’s going to be 50:50. If you can make the experience slightly better and the cost is close then they will go with the connected one.”

What would Majzoobi do differently with Bitlock, if he could have the time again? “It’s a hard question. I would probably do less. We did a lot of stuff. And we shouldn’t… As inventors we get really excited with ideas. ‘Hey, let’s implement this, let’s do this.’ And then also when the customers ask us are you going to add this? We, as startup founders, feel like we have to say yes we want to add this feature to make you happy. But then we don’t really understand how much effort goes to add a simple feature.

“So if I were to go back I would probably say more nos to features and/or parts of the product that would make things easier. And taking it more slowly and try to focus more on marketing, sales and do less on product.”

And what does he think of the crowdfunding process now, after some 2.5 years hard grafting to deliver on his original vision? “I have a bittersweet relationship with crowdfunding,” he tells TechCrunch. “I think it’s a very rewarding platform but sometimes it’s very draining for the project creators and at the same time it can get very frustrating for the backers.”

The mindset of some backers is out of kilter with the creative impulse that drives makers, he adds. “My point is that backers are not really seeing the point in crowdfunding. Lots of them. Some of them see the point and they understand it’s a creative process… but to fix this I think backers should be invested more in the product. I think the best way to go around crowdfunding is asking backers to put in say 50 per cent — or whatever amount it is — for the product and then pay the other 50 per cent at the time of delivery.

“It also helps with the project creators to work with those limited resources. Sometimes project creators get the whole cash and they burn it in two months… but if they have this milestone to get paid again at the end of the project they are going to be working on their budgeting more carefully. It could be structured in a better way or backers could have some incentive to buy another product at say 50 per cent discount when the product comes out.”

“Extra levels of incentives or penalties for both sides should be worked into the process,” he adds.